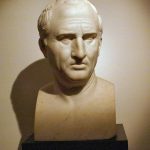

To this day Cicero appears to us as a model of an ideal politician, lawyer and speaker, standing up for his homeland and his clients. Detection of the Catilinarian conspiracy in the late 60s of 1st century BCE brought Cicero enormous glory and splendor, which, however, led him to a pathetic vanity.

Rescuing Rome from destruction and a bloody revolution meant that Cicero was awarded the title pater patriae , meaning “father of the homeland” – one of the most honorable titles that could be obtained in ancient Rome. The people and the Roman elite recognized him as the savior and hero of his homeland. All this glorification, however, proved that Cicero was not quite as great as we thought.

We know, among others, that Cicero tried to persuade one of the historians friend – Lucius Lucceius – to describe the events of the conspiracy of Katilina and show Cicero in a favorable light. Cicero himself gives us proof of this in one of his letters, where he writes: “I wished with an unbelievable but, I believe, not a reprehensible desire for my name to shine and make itself famous thanks to your writing”. Moreover, Cicero also wanted a Greek poet, in exchange for representing him in the courts, to write a commendable epic in his honor.

It is worth noting that this pure vanity of Cicero was already ridiculed by the ancients. Apparently, the great speaker, long after Katilina’s death, bragged and emphasized his merits for the good of the homeland. A fragment of the poem that Cicero wrote to celebrate his consulate has survived to our times. It did not survive completely, but thanks to many copies, part of the text is known, including O fortunatam natam me consule Romam, meaning “Oh, how Rome lived happily, when I was a consul”.