Remains found in the Roman cemetery in York, England, prove that the city – once an essential bulwark of the Roman frontier in the far north – was home to both local residents and thousands of immigrants.

In a paper published on Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications, Trinity College Dublin geneticist Dan Bradley and his colleagues analyzed preserved DNA in seven skulls found in an ancient cemetery. Six of them, they found, had DNA matching people living in modern-day Wales. However, to the scientists’ surprise, one of the men had travelled a long way from the other end of the Empire. It is certain that he was not from Europe; it is possible that he had roots in Palestine or Saudi Arabia.

To confirm the results, Gundula Müldner from the University of Reading examined the chemical structure of the teeth. The differences were dramatic. The man with a different genotype had to live in a dry and warm climate – similar to that in the Nile Valley.

Other evidence suggesting that Roman citizens moved throughout the Empire can be found in written sources or burials. In York, the grave of a woman who came from Africa and was wearing an ivory bracelet was found.

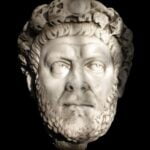

The skeletons, analyzed by Dan Bradley’s team, are located on the former outskirts of Eboracum, a Roman camp and centre that was one of the largest in Britain 1,800 years ago. A total of 80 bodies were found in the cemetery. The buried had traces of healed wounds or bites from large predators (lions or bears). Interestingly, half of the skeletons were beheaded. All the deceased persons were under 45 years of age and well-built. Scientists believe that they could have been gladiators or Roman soldiers.