Chapters

The fall of the Roman Empire is a long process spanning several centuries. To this day, scientists are arguing about when the progressive disintegration of the Roman state began and what were its causes. As soon as we start talking about the decay of great empires, it is ancient Rome inevitably that first comes to mind.

Edward Gibbon, one of the most famous scholars of the history of ancient Rome, had no doubts: all evil began towards the end of his reign Marcus Aurelius, and the main reason was the fall of ancient Roman virtues, which was caused, among others, by the spread of Christianity. Some traditionally minded historians agreed with Gibbon, others pointed to the political crises and constant invasions of the German barbarians plaguing the Empire.

Scientific theories

Currently, we distinguish various theories and explanations for the fall of the Roman Empire in the west. They can be generally classified into four superior groups:

General decay and weakening of the state

In this approach, historians take into account various aspects that contributed to the weakening of the political power of the state.

- The decline of ancient Roman virtues was intensified by the spread of Christianity – the representative of this theory was Edward Gibbon – author of the book “The Twilight of the Roman Empire” (1766-88). The historian also emphasized the great influence of the barbarian tribes on the fall of the Empire, which eventually yielded to the pressure of its neighbouring neighbours. In addition, he pointed out the negative influence of Christianity on all aspects of the Empire, especially the military.

- Writing in the 5th century CE, the Roman historian Vegetius even pleaded for any reform of the Roman army, which was at a tragic level of training. Historian Arther Ferrill has suggested that the weakening of the army was due to the massive influx of the Germanic element into prestigious legions. “Germanization” of the military structures led to a lower discipline and rigour and to a lower level of loyalty of the troops towards leadership. Ferrill also agrees with another historian, AHM Jones, that the decline in trade and industry was not the reason for the fall of the Empire. However, the agricultural decline was deeply significant, largely due to the barbarian invasions and the imposition of increasing taxes on society.

- Historians Arnold J. Toynbee and James Burke argue that, in fact, the Empire’s internal system was “rotten” and in need of repair. Revolutionary reforms were needed that neither emperor was ready to carry out. The Romans did not have any budget system, which led to a waste of all resources. The economy was focused on exploitation, which was carried out in the rich, conquered territories. There, too, high taxes were introduced, which led small farms either to poverty or to dependence on the influential elite. As the main sources of financing for the army were limited, the state was forced to tax Roman citizens with taxes. With the growing pressure of the barbarian peoples on the borders of the Empire, the need to finance the army also increased. The situation eventually became so strange that the barbarian armies were sometimes better equipped than the Romans themselves; not to mention larger numbers. Over time, the population of Roman cities began to see the Romans as occupiers, exploiting their subjects, and the barbarians as liberators.

- The historian Michael Rostovtzeff and the economist Ludwig von Mises agreed that economics played a key role in the fall of the Roman Empire. According to them, in the 2nd century CE, the Roman Empire had a developed market in which trade was relatively free. The fees were low and the top-down regulations had little effect on turnover. However, with the denomination of the currency in the 3rd century CE, there was inflation. Seeing the negative side of this situation, Constantine the Great decided to carry out the currency reform that was implemented before the barbarian invasion in the 5th century CE – no, however, it significantly changed the state’s situation. According to Rostovtzeff and Mises, artificially low prices led to a loss of food, mainly in cities where inhabitants made their livelihoods depend on them. Despite legal regulations aimed at preventing the depopulation of cities, a gradual decline in population from urbanized areas to rural areas could be observed. The population decided to change their profession – from trade to agriculture. In this way (with high taxation) there was a decrease in trade turnover, a decrease in innovation and state revenues.

- Bruce Bartlett is looking for a denomination during the rule of Emperor Nero. Bartlett believes that successive rulers, wanting to maintain the loyalty of larger and larger troops, decided to spend more money and pay more and more money. The climax was the 3rd century CE and the need to satisfy the exorbitant demands of soldiers at all costs. The lack of consent or the prospect of paying further funds led to the overthrow of the emperor and the appointment of a new candidate in his place. The rulers, avoiding burdening the population, decided to requisition (wherever they could) physical goods – for example, grain and cattle from farmers. As a result of such activities, social chaos ensued, which was compounded by forcing people to hold their functions and professions. In this way, farmers were tied to the ground, and the soldiers’ children had to join the army. Great numbers of people migrated to the provinces, where they were looking for a chance to become independent from the ruler and to secure basic life opportunities. With time, separate estates began to take shape, which did not take part in state trade and formed a kind of community. These were the beginnings of feudalism.

- The British historian – Adrian Goldsworthy – saw the main reason for the fall of Rome in the military aspect. Endless civil wars for supremacy in the Empire, a weakening army, the reluctance of men to join the army, and the growing pressure of barbarians on the borders led to the decay of the Empire. The progressive weakening of the central power, social and economic problems of the state led to the weakening of the fighting strength of the legions, which was extremely important for the stability of the state.

A one-stop approach

Theories suggest one aspect of the collapse of the Roman Empire.

- Diseases – historian William H. McNeil recalls that around CE 165 the Empire was hit by the terrible plague of Antonia, which was brought by Roman troops returning from the east. For about 20 years, the pandemic (smallpox or measles) killed almost half of the Empire’s population. In the 3rd century CE, another plague struck the empire – the so-called Cyprian. Pandemics led to a marked depopulation of regions, which had a natural impact also on trade and military effectiveness. The Eastern Empire is believed to have survived because it had a larger population within its borders. It is worth adding that epidemics had extremely easy ways to create new disease outbreaks. The cities were crowded and the poor mingled with the aristocracy in public places. In addition, the cities were supplied with water, which was a great “guide” of pathogens. The Germans, unlike the Romans, were less prone to disease. They did not live in such a crowd, they did not have such wide access to water, and they drank mostly boiled water. Thus, fertility and population growth were much greater among the barbarians than in the Empire.

Archaeologists have found that from the 2nd century CE, urbanized regions gradually decreased in numbers, and the legally regulated so-called Uninhabited lands (agri deserti) encompassed other areas dangerously. The smaller population translated into lower tax profits, which hit Rome’s finances. - Environmental degradation – approach suggesting the impact of deforestation and degradation ecosystem to decline in population and income. Deforestation during the Roman period resulted from the territorial expansion of the Empire, the expansion of its population, large-scale agriculture and rapid economic development. Rome has led Western Europe to a large extent toward development, which has resulted in heavy deforestation around the Mediterranean Sea.

The influence of Roman culture on the state of the ecosystem of the Mediterranean region under Roman rule can be seen with the naked eye. A great example is a macchia, also known as macchia, which is a secondary plant formation found in wetter habitats in the Mediterranean. It was created in the place of sclerophyllous, mainly oak forests, destroyed by the Romans. Hence, Italia is largely a low forested area dominated by shrubs. Continuous cultivation of land resulted in the formation of wastelands and marshes. There were also natural disasters: floods (even Rome was affected by this; the first large flood was recorded in 241 BCE), mudslides, and famines.

The Romans also influenced air poisoning. A large number of industrial centres required large supplies of fuel (coal, wood), and thus the air was poisoned with excreta from furnaces and smelters. Of course, these effects of the activities of the Romans do not have the scale of today’s civilization. It should be noted, however, that at that time, Roman civilization could be considered one of the least eco-friendly in the world. - Lead poisoning – Jerome Nriagu in 1983 emphasized that lead poisoning could have had a big impact on the collapse of the Roman state. The commonly used lead pipes, pots, and defrutum sweeteners were bad for the health of the Romans. Lead is removed very slowly from the human body, it accumulates mainly in bones and blood (and it travels to all organs). The effects of its long-term use can be many diseases: cardiac arrhythmia, kidney disease, anaemia, and circulatory failure, which almost always leads to death.

Pharmacologist John Scarborough, however, accuses Nriag of a number of lies and emphasizes that the Romans were aware of the negative impact of lead on health – even mentioned by Pliny the Elder1or Vitruvius2.

Problem stacking

- JB Bury – criticized Gibbon for his vision of seeing the reason for the fall of Rome in expanding Christianity. As the Eastern Empire notes, it was strongly Christian and survived for many more centuries. Moreover, he believes that Gibbon’s approach is too single-causal and incomplete. Bury argues that the fall of Rome resulted from a series of complex events, which precludes listing of general causes. Rome was plagued by many crises that occurred at the same time: economic regression, invasion of the Germans, depopulation of Italy, the dependence of the army on the Germanic foederati, betrayal of Stilicho, the loss of the will to fight, the death of Flavius Aetius or the lack of an outstanding leader of Aetius. It was a series of mishaps and circumstances that led to a great catastrophe.

- Peter Heather – claimed that despite the internal problems of the Empire throughout history in the 1st, 2nd and the middle of the 3rd century CE, it showed stability. The first major threat was the formation of the Sassanid Empire (226-651 CE) in today’s Iran. Long wars with its eastern neighbour finally ended successfully for Rome. However, the conflict resulted in a decrease in income in the provinces, which in turn was to have a bad (long-term) impact on the state. Economic weakness led to the social decline, which also coincided with the “domino effect” of the Huns. Heather, like Bury, believes that the fall of Rome was not inevitable. The death of the Western Roman Empire resulted from historical misfortune – the overlapping of negative events.

- Bryan Ward-Perkins – the “vicious circle” theory involving political instability, foreign invasion, lowering tax revenues.

Transformation

In the 19th century, some historians focused on the continuity of the Roman Empire as post-Roman Germanic kingdoms.

- Fustel de Coulanges believes that the barbarians simply contributed to the transformation of Roman institutions. Henri Pirenne, in turn, stated that the barbarians came to Rome not to destroy it, but to obtain certain benefits – as a result, the Romanness and way of life of the Romans were preserved. Pirenne, in his theory, also claims that the subsequent Frankish state can be considered an entity that continued the traditions of Rome.

- Lucien Musset – a French historian – stated that the medieval world was formed as a result of the collision of Greco-Roman civilization with Germanic civilization. The Roman Empire did not collapse but only transformed – more precisely, the Germanic population adopted the values of the Roman world.

- Late antiquity historians such as Peter Brown believe that Rome cannot be said to have fallen as such. The system of values of the Romans existed in the areas conquered by the barbarians for the next decades, which prompts the conclusion that there is no separation between the ancient and medieval epochs. It was too slow and a long process to be able to mark the time limit.

Economic and monetary crisis

Most scholars agree that one of the main reasons for the weakening of Rome (which allowed barbarians to cross the Rhine and Danube with impunity and then settle in different parts of the Empire) was the economic crisis that had been ongoing since the 3rd century CE.

Initially, Rome began trading in cattle and brown currency; back then it was just a poor settlement made up of refugees and outlaws from various surrounding kingdoms. When these people began to organize and conquer their neighbours, they adopted new, higher standards.

The breakthrough was the introduction of the monetary system based on silver and gold coins, initially in the Greek standard. Over time, the Romans developed their own system based on silver coins called denarii and gold coins called aureus. It was then that Rome transformed from a Republic into an Empire and grew in strength.

Huge prosperity has spread to everyone; each Roman wanted more than he had, and the army and administration grew to protect and enlarge the state and to care for society. Cities developed more and more dynamically, especially the capital, the emperors, wanting to please the society, erected huge and rich public buildings, such as Circus Maximus or Colosseum, they did not spare themselves by expanding their headquarters.

More and more money was needed for all this, while the stocks of gold and silver ran out. Expenses grew and money was scarce. What did the emperors and the administration of the Empire do about this? The decision was made to mix pure silver and gold with worthless metals, mostly copper, in a way that was quite imperceptible – the result was twice as many coins.

Such practices began to occur sporadically as early as the 1st century CE A great example is the coin antoninianus, which circulated thanks to Emperor Caracalla on at the beginning of the 3rd century CE, they were like double denarii, i.e. one antoninianus was equal to two silver denarii. Except that the antoninianus was only visually bigger because 60% of its value was copper. The more the expenses grew, the Empire produced less and less valuable coins. Every day there were more and more of them, the supply of currency was growing at an alarming rate, and there were less and less gold and silver in them. The reform policy was also attempted by Septimius Severus (193-211 CE). He began by devaluing the denarius, but the decline in the value of the Roman currency only undermined trust in the Empire. It got to a point where bankers in Egypt and the Middle East refused to accept it. Military commanders also did not want to be rewarded with dwindling money, they preferred to grant land. When they did not get them, they rioted.

At the end of the 3rd century CE, the corruption of money led the Roman Empire into a serious crisis. When Emperor Diocletian took power in 284 CE, the crisis was raging for good. In an attempt to save the day, the Emperor issued the Edict on Maximum Prices in 301 CE, which imposed on society maximum prices for goods and services; severe penalties for non-compliance. Most of the merchants and traders did not follow the edict because it was unprofitable for them with rising inflation. They went to the black market.

Also, unemployment grew, people were losing their fortunes and starving. The government tried to solve the problem of hunger by means of social support, which had been used much earlier, making citizens dependent on the Empire. The government tried to solve the unemployment issue by employing people to build public buildings for which huge amounts of money were spent. Huge money also went to the army, which had to defend the Empire against the increasingly bolder aspirations of its enemies.

Diocletian ordered more and more copper coins to be minted to cover all these expenses, eventually leading to the first-ever hyperinflation. In order to buy basic products, the Romans had to spend sacks of copper worthless coins. The Empire was headed for the bottom. The rivals just waited for such a moment for the colossus to lose his leg. Earlier, foreign people from conquered provinces and foreign territories flowed into the Empire, leading to the degeneration of society, and destroying the Empire from within.

It should also be mentioned that with the final stabilization of the Empire’s borders and the cessation of conquests, latifundia based on slave power lost a rich source of labour. There is no doubt that the next waves of Germanic invasions dealt a huge blow to Rome (also caused by economic factors – the Germans fled to the borders of the Empire against the aggression of Asian nomads, who were probably driven out of there by the lack of food). It is worth noting that the Germans did not even dream of overthrowing the Empire at that time. The more dangerous effect of their actions for the existence of Rome was rather the deepening of the economic decline.

The costs of maintaining the armed forces exceeded the capacity of the state budget. The aforementioned inflation appeared, followed by the economic crisis, rising food prices and social unrest. Meanwhile, the borders of the Empire were attacked by barbarian peoples from the deep inside.

The Roman Empire in western Europe finally collapsed in the 5th century CE Again, it is worth noting that the final blow that led to it was largely economic in nature. The Western Empire was only able to deploy new armies, defend itself, buy out from invasions, and bribe barbarian invaders as long as it had its last secure economic base in North Africa. But it was this last source of grain, people, and money that suddenly “dried up” in 429 CE when the North African provinces were occupied by the Vandals. If you look for the real cause that actually ended the life of the Roman Empire in the 5th century CE, it was precisely the economic blow caused by the loss of Africa, not insignificant though symbolic, events from 476 CE.

Credited causes of the fall of the Roman Empire

Below are the various causes and factors that together influenced the fall of the Roman Empire in the West.

- Bureaucracy, corruption, privatization of officials, irregular tax flow to Rome;

- The political culture of the new elites did not match the times of the Catons, Scipio, Cicero, etc. It should also be remembered that most often new people coming to power, more eager for wealth and money, often increased them at the expense of the old elites, who either it was dying out naturally or it was being destroyed by homines novi;

- The great migration of peoples and invasions on the borders of the Empire;

- Economic crisis – the devaluation of money, inflation, lack of cheap labour;

- The crumbling of an elite capable of managing the Empire, whether in the course of wars or as a result of internal upheavals. People who slowly replaced their predecessors at the top of power (note that some emperors were non-Romans – Maximinus Thrax), usually from lower echelons of society, not they were able to deal effectively with the increasing difficulties in various fields;

- Internal struggles for power, instability, civil wars;

- Deforestation and land degradation may have had an impact on population decline and economic decline;

- Cessation of territorial conquests in order to defend the conquered territories, thus reducing the influx of slaves, who were the main labour force in the Empire;

- The spread of Christianity – Gibbon believed that Christianity emerged in Rome as a kind of “decay process” within the Empire and became the main cause of its gradual decadence and decline. Today, this Gibbon causal sequence has been abandoned due to historical research focusing on economic factors and class structures;

- Disease – plagues and declining fertility caused the overall decline of the Empire’s forces with unchanged borders;

- Lead pipes, pots and defrutum sweetener – lead from the human body is removed very slowly, it accumulates mainly in bones and blood (and with it it goes to all organs). The effects of its long-term use can be many diseases: cardiac arrhythmia, kidney disease, anaemia, circulatory failure, which almost always leads to death;

- Too far boundary Empire, too few troops to hold buffer zones;

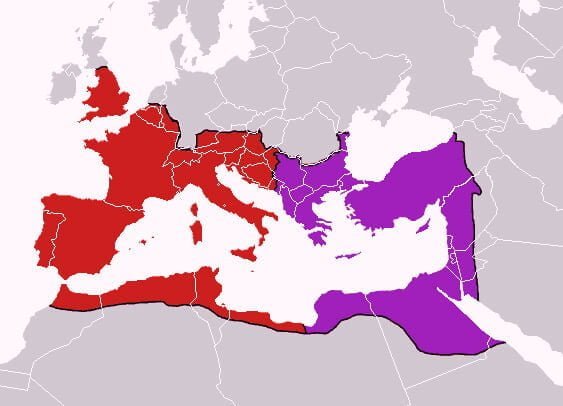

- The division into Eastern and Western Empires in395 CE – doubling of bureaucracy and instability. Later, frequent competition between state actors, not cooperation.

What did CE 476 really mean?

The disappearance of the imperial institution in the West could be read as the restoration of the old state of affairs in favour of the aristocracy, in a situation of political advantage before the advent of the successor Princeps titles Octavian Augustus. This restoration of the old order was the deliberate act of the barbarian king who reigned over Rome – the Odoacer. Their contemporaries were not aware of this fact, just as they did not notice the disappearance of the imperial institutions in its western part. This was due to the relative “habituation” to the interregnum and the growing importance of the barbarian patricians in the 5th century, who were often entrusted with the function of magister militum. Thus 476 CE passed virtually unnoticed. The date 476 CE remains the mainline between antiquity and the Middle Ages. In fact, this point is only sealed by the decay of the Empire, which has been hanging in the air for years, following a long political and constitutional torment. One should also note the widespread pessimism and apathy of Roman society, which could be noted in every aspect of the life of the state.

The dethronement of the last Western Emperor Romulus Augustulus was first noticed by the rhetoric and Byzantine official Marcellinus Comes, in his book “The Chronicle” (6th century CE) he wrote that “the Roman Empire in the west […] experienced death with Augustulus”. Contemporary historiography, or a part of it, has for some time been questioning the validity of the claim that the dismissal of a young Roman marked the boundary between historical epochs. One of the most famous period-denying scholars is Arnoldo Momigliano, an antiquity specialist, who wrote the phrase “fall without noise” – thus describing the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

From the 18th century onwards, we have been obsessed with the fall of the Roman Empire: this fall has taken on the archetype of every fall and also a symbol of our fears. The first paradox is that a basic book like the one by Gibbon (The Twilight of the Roman Empire, 1776-88) only spread this obsession. The second paradox is that very few contemporaries (as far as we can infer from the sources) realized that the removal of Romulus Augustulus from office also marked the end of the Roman Empire in the west. The Roman Empire in the west fell without making any noise in September 476. In antiquity there were violent falls, and they were considered as such, without relief and often without mercy on the part of contemporaries. And this is how the concept of succession of empires was created […].

When Assyria, Babylonia, Persia, Macedonia ceased to exist one day, it was immediately recognizable. Also in the history of the Greek thalassocracy, from Cretan to Athenian, and a comparable, but not identical, series of hegemony (Sparta, Athens, Thebes, Macedonia), historical periods were formed that were recognized and identified by contemporaries and their successors. […]

However, when it comes to the coming of the true decay of the Western Empire, when the Emperor of Rome “disappeared” in CE 476, there is no dramatic moment – military conquest, assassination of the ruler, physical destruction – which could echo comparable to those that accompanied the fall of Nineveh, Babylon, Persepolis, and finally Athens, Sparta and Thebes. If you can find any event comparable to the fall of Nineveh, it was the conquest and plunder of Rome in CE 410 that inspired Saint Augustine so strongly. Nevertheless, the same conquest and plunder of Rome, seen in retrospect, appeared as an indecisive clash, perhaps discouraging dramatization, at least the dethronement of Romulus Augustulus in September 476 concerned only Italy, for the inhabitants of which, if they were not eyewitnesses of the events, it was neither legally nor politically clear. The relationship between Odoaker and the emperor of the eastern empire remained uncertain.

The empire was never formally separated, and the most obvious manifestation of the dethronement of the Roman Emperor must have drawn the attention of Constantinople as the true center of the Empire. The fact that Romulus Augustulus, still young and personally completely insignificant, was generously sent by Odoacro to live in Campania with his mother and received a substantial payment.his contribution to the drama of the fact of this ex officio removal3.– Momigliano Arnoldo, La Caputa senza rumore di un impero nel 476 d. C., [in:]Sesto contributo alla storia degli studi classici e del mondo antico, Roma 1980, pp. 159-161