One of the special forms of public service was military service. The army is one of the structures most closely associated with the state apparatus, and for this reason, service in it, from historical times, meets with different attitudes towards it. Very often, a view of the army is tantamount to a view of the existence of the state.

During the period from the foundation of the Church to the 1980s, we do not have information about the service of Christians in the legions. The research conducted since the beginning of the 20th century allows only to formulate a thesis about the pacifist attitude of the early Church. The source material is missing. The references to the military colour appearing here and there are only ways of expression, comparisons. An example would be the “Letter to the Corinthians” of St. Clement of Rome from the last years of the 1st century CE, the author writes in it, inter alia, thus: “Let us, therefore, serve, brethren, with all zeal under the command of an impeccable leader. Let us think of the soldiers on a military expedition, how disciplined they are, how obediently they obey the orders of their commanders”. We can see that we are dealing only with literary tricks and not with an opinion about the military service of Christians.

A careful review of all available information shows that until the time of Marcus Aurelius (160-180 CE), no Christian became a soldier, no also a soldier, when he became a Christian, did not remain in military service.

We who were filled with war, and mutual slaughter, and every wickedness, have each through the whole earth changed our warlike weapons, our swords into ploughshares, and our spears into implements of tillage, and we cultivate piety, righteousness, philanthropy, faith, and hope, which we have from the Father Himself through Him who was crucified.

– Apologeticus. Dialogue with Trypho

Christians refused to take any part in the state administration and defence of the Empire. It was impossible for a Christian to become a soldier, dignitary, or ruler without renouncing a more sacred duty. After departing from the principles professed by the early Christians and openly departing from the teachings of Christ, the situation changed.

The first testimonies of Christian service in the army date back to the Marcomannic Wars (167-180 CE). “Apologetic” by a lawyer from Carthage – Tertullian – contains a fragment about Christian soldiers who reportedly brought rain on their opponents through prayers. In light of the facts known today, we consider this story to be the Christian version of the legend of “Rainy Jupiter” (Iuppiter Pulvius) and therefore a pagan legend. This legend, described in the letter of Apollinarius of Hierapolis in Eusebius of Caesarea (“Church History”), which has not survived to our times, was elevated to the rank of a description of God’s interference, in short – a miracle. The history of the XII legion from this event called “Thunderer” (fulminata) inflamed the readers of “Church History”. Some sought in it the apology of Marcus Aurelius, who was to release the soldiers of the 12th Legion from punishments for their faith. Anyone who knows the attitude of a philosopher on the throne towards the religion of Christ should have no doubts about the correctness of his views in this direction. The Danube in the reign of Aurelius and his co-ruler, Verus, was called the “Bleeding Border”. The invasions of the Quadi, Sarmatians and Marcomanni resulted in the expansionist policy of the rulers who did not follow the order of Octavian Augustus not to cross the “natural boundaries” on the Rhine-Danube line by the empire.

The most famous Christian writers had a negative opinion about serving Christians in the army. Justin Martyr argued that Christians, being persecuted by Rome, could not be at his service at the same time. Tertullian had more to say on this subject. When asked whether a follower of Christ can serve in the army, he replied: “The Lord, disarming Peter, thus deprived every Christian of the sword. You must not have any equipment, since the activities with its use are not allowed.” In his work “On the wreath” (De corona), Tertullian gives the example of a soldier not accepting donativum because “you cannot serve two masters”. He may wonder why the legionary refuses to accept the award in sesterces. The point is that when you serve in the army, you serve the emperor, and he calls himself a god. According to Tertullian, military service is in itself an apostasy.

Moreover, Tertullian lacked anarchistic convictions, he was convinced of the need for a strong state, and even argued that one should pray for the emperor and be a loyal subject. At the same time, one cannot take part in public service, because it requires sacrificing to idols, but first of all, serving another god – the emperor.

Tertullian’s position coincided with that of Origen. But while Tertullian reasoned in legal terms (a rhetorician by education), the latter justified the existence of the state theologically (theologian from the Alexandrian school). In his famous work “Against Celsus” (Contra Celsum) he argues that the unification of the lands under the rule of Rome makes it possible to proclaim the Gospel. It is known who united the Roman Empire – the army. And the consolidation process took place through wars. at this point, the opinions of both do not match – the Carthaginian condemns all kinds of armed protests, while the Alexandrian accepts the possibility of “just war”, although he does not recognize the participation of the baptized.

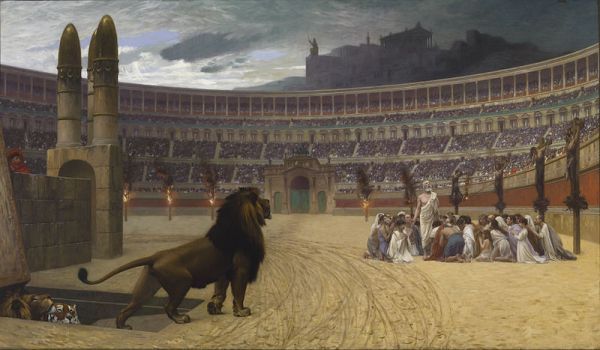

Lactantius calls military service “public homicide.” “Thus, neither will the righteous, whose military service is justice itself, be allowed to serve in the army, nor will he be allowed to accuse someone of a crime punishable by death.” Christian Cicero, as he was named in the revival, made his own opinion on the military and killing in the work entitled “God’s teachings” (Divinae Institutiones). For him, military service in general, not only for Christians, is a sin. Lactantius writes: “So there is no exception to this command of God, and it is always lawless to kill a man who, according to God’s will, was to be a holy and untouchable creature.” This radical approach was not new, however. A whole century earlier they were presented by Cyprian of Carthage. He turned to the way of Christ and devoted his whole life to calling others to conversion. He promoted ascetic life and was a lover of Tertullian’s writing. By abundantly using the thoughts in the works of his master, Cyprian was able to avoid his violence. He included the condemnation of the bloodshed in the treatise “To Donata” (Ad Donatum). “It drips the world with mutual blood: it is a crime when murder is committed by individuals; it is called a virtue when it happens in public (…) A gladiatorial game is prepared so that cruel eyes graze blood. so that someone killed for a punishment more expensive is killed. A man is killed for the pleasure of man, and that someone can kill, there is experience, there is practice, there is art: not only is a crime committed but also taught. ” These words reflect well the atmosphere in the legion camps.

The column in the middle of the arena is a monument to persecuted Christians killed by Roman authorities.

It is also worth mentioning the sentence Hippolytus. In the “Apostolic Tradition” he denies soldiers the right to be baptized unless a candidate leaves the service. But it is also worth emphasizing that, in addition to the sword service, the service in the army included vigilum, i.e. fire brigades in cities, night guards and even civil courts (the example of Philoromos of Alexandria mentioned by Eusebius). It seems that the above judgments were compatible with the Gospel prohibition of killing or at least did not contradict it.

The third century was the period of the triumph of Christianity. For the time being a moral one, because almost the entire 4th century CE had to wait for the final recognition. Like most great successes, it began with a failure – the persecution of Septimius Severus. The situation was calmed down by his successor – Caracalla, ordering the prosecution of Christians to be stopped. In CE 212, he proclaimed the constitutio antoniniana which conferred Roman citizenship on all inhabitants. This not only produced fiscal revenues; it mainly contributed to the rise in pro-state sentiment. The first years after the edict were followed by the first Christian testimonies condemning desertion. Over time, more and more Christians choose soldier’s bread. The army offered the possibility of social advancement. Veterans were released from some tax benefits, they also received a plot of land as “retirement” security, as we would call it today. Christian soldiers in the third century were evidence of the process of integrating religion into the social structures of the state.

It is difficult to cite cases of refusal of service in connection with professing Christianity because there were not many of them. However, it should be noted that their number grew slightly over the years. There is an interesting document dated 343-351 CE, and that is a letter from a Christian officer to the bishop of Alexandria, Paulos. In this letter, the officer asks how to deal with the deserter, and the bishop advises him to forgive him this time, at the same time admonishing him to apply the statutory sanction against the recalcitrant soldier.

In general, research into the military service of the early Christians ran into difficulties today due to a lack of significant archaeological and historical discoveries.