Chapters

The first eight days of the birth of the child (primordia) were filled with religious ceremonies. The child was visited by family friends, bringing him all kinds of gifts, such as cakes, flowers, etc. On the ninth day, the child was officially accepted into the family by the nickname (praenomen). Complementing the formalities, were religious ceremonies when it was followed by purification and sacrifice to domestic deities. That day was called either dies lustricus or dies nominium . The entire ceremony on the ninth day was private. From official activities, it was still necessary to submit the child’s name within 30 days of birth to praefectus aerari, while in the provinces to tabulari publici.

Children up to 7 years old were brought up under the care of mothers and domestic service. The mother was responsible for the moral education (pietas) of her sons and daughters. After the age of about 7, the child started education. With regard to boys and girls, only the duration varied. The boys were educated up to the age of 15, while the girls were up to the age of 13. The boy from the age of 7 went under the full protection of his father. The mother took care of her daughters, teaching them household, spinning, sewing and sometimes music.

The father responsible for the education of his son (doctrina) prepared him for private life (running a farm, supervising and managing slaves), for public life (exemplary fulfilment of his duties towards family and service, towards friends and the state) and for military service (games, plays and exercises outdoors, using weapons; throwing a spear and using a shield, hand-to-hand combat, horse riding, swimming and getting used to discomfort, hunger and cold).

The boy usually learned to read from his parents; usually based on the “law of XII tables“, which was also the foundation of civic and patriotic education; they often learned it by heart and recited passages on various occasions.

To deepen patriotic feelings, he listened to stories about the lives of national heroes, learned ballads about their heroic deeds on the battlefields, learned the merits of great politicians, and learned the history of his native country.

At around 17 years of age, the young man dressed in a gown as an adult, he usually left his family home and, under the protection of his father’s friends, was able to participate in the public and political life of the country. Usually, after one year of military service followed.

The first year he served as a simple soldier, then worked in the staff, learned command and wax strategy and took part in military expeditions aimed at increasing and strengthening the power of the state. Military service opened the way to the highest positions and offices.

Education

Children started education, as I mentioned when they were 7 years old. Less affluent citizens, or simply plebs, sent children to public, elementary schools, often located in public buildings, or in tabernacles of Roman houses. They were usually run by people of unknown origin, freedmen. Schools were located in the arcades of the market, on the porches and arbours – protecting the teacher and student from the heat of the sun.

The teaching profession was in widespread contempt, moreover, people for this profession were recruited mainly from slaves or freedmen, most often of Greek origin, who almost monopolized this profession. Parents themselves paid for education, which was often associated with obtaining a low salary for educators. Often, people engaged in this profession sought additional activities to be able to lead their existence under normal conditions. Over time, however, some schools, or rather teachers, gained some prestige, which could eventually result in the patronage of a wealthy Roman by paying him a salary (fee).

At this point, it is worth mentioning that in history it is assumed that the first public school was founded in the third century BCE by Spurius Karwilius, and the state-paid school was founded during the reign of Vespasian.

The school year began after March 23. Not only holidays were free from school, but also all nundines.

Classes began before sunrise when all of Rome was coming to life. The students went to school, provided with candles, which were probably served to them during the first hours of their stay at school. During the lesson, one break for meals was ordered, and after that, the education continued in the afternoon. For instilling knowledge, a cane (farula) was sometimes used to teach students ‘concentration’ and ‘pursuit of development’.

In the 3rd century BCE, arithmetic teachers appeared. calculators (from the word calculus , i.e. a smooth calculating pebble). The curriculum included reading and writing, the beginnings of arithmetic, stories about the history of Rome, ballad recitation, singing patriotic songs and reading XII tables.

Teaching was conducted using the memory method; physical punishment – flogging – was the most frequently used teaching agent. Therefore, the vicinity of the school for the surrounding residents was bothersome, the more so that learning (and therefore also the beating and crying of children) began in the early morning. There was no homework, and numerous holidays and celebrations, as well as holidays during summer and breaks at harvest and vintage, meant that there were many days off from school. Elementary schools were also attended by girls . In times of the republic, educated women could often be found; they exerted a great influence on the intellectual life of the country.

The boys in well-off homes were under the constant care of a teacher (pedagogus , comes , custos or monitor), which he served the function of both educator and teacher. Initially, learning included reading, writing and accounting elements. Over time, the curriculum has changed. Finally, a three-stage teaching process was developed, which was led by various teachers who were:

- Literator – he was a first grade primary school teacher. He taught children to read and write. Under the guidance of an accounting teacher (calculator , librarius), children learned basic mathematical operations. These exercises were first done on the fingers, with the fingers of the left hand used to represent unity and tens, and the right one hundred and thousands. Later, they reached for pebbles to finish on the abacus. In addition, children were taught the multiplication table to which memory was best used. The teacher preached and the children repeated in a chorus. The most important scientific help of the literary was the horn which was a “repressive” tool.

- Gramaticus – its main task was to teach students how to speak and comprehend content. Interpretation and stylistic principles prevailing in poetry and all literary art were also taught. In addition, students were acquainted with music, astronomy, philosophy, geometry and most importantly, grammar. The basic textbook was Homer. In addition to his works, the classics of Liwius Andronikus were also read. It was not until the time of Octavian that there was an influx of younger authors, i.e. Horace, Ovid and others. The reading of the works was accompanied by linguistic and grammatical analysis. Studies with the rhetor often took place in the tabaernae cavities, whether it was the Julium Forum or the former Trajan Forum exaster. The age at which rhetoric started learning depended on the parents and also on the development of the young man.

- Retor – Pronunciation teacher. The science consisted of the theory of pronunciation and exercises, which took two forms: suasoriae – speeches on a given topic (monologues) and controversiae – a combination of prosecutor’s speech and defense. In addition, students made a description of historical figures presenting a specific factual situation and discussed possible scenarios if minor modifications were made to the husband’s decisions. The studies were certainly complemented by public speeches (declamatio) so important to the responsibilities of public life.

The culmination of education was philosophical studies in Athens, not without exaggeration called the university for the Romans.

The rapid transformation of Rome – from a small state into a powerful empire – brought about great changes in social and political life. Already in the third century BCE the aspiration of higher states (family and financial aristocracy) to provide their children with education corresponding to their ambitions, supporting the ability to lead in public and state life, was intensified. They want their children to be distinguished from the general public not only by their wealth, clothing and jewels, but also by their mental level: knowledge of Greek and its literature, and knowledge of dialectic and rhetoric.

For their needs, Greek teachers (after the occupation of Greece by Macedonia, and then after the conquest of Greece by Rome), began to set up paid high schools on the Hellenistic pattern (according to Isocrates’ instructions). They taught Greek grammar and rhetoric, Greek literature starting from Homer, then Hesiod. Then they went to the later epic, lyrical and dramatic works by analyzing the read texts in terms of grammar, etymology, history, methodology, philosophy, etc. showing, among other song features, its pros and cons. Thanks to this, young people gained comprehensive literary and encyclopedic education.

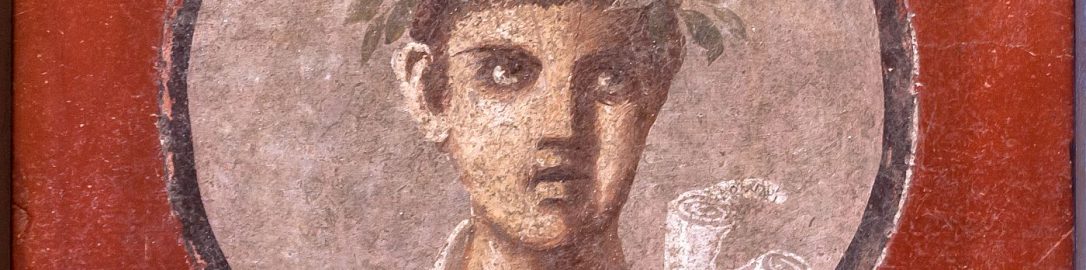

Boy poet

Quintus Sulpicius Maximus was a young poet who became famous for his participation in an important poetry competition in Rome. At the age of 11, he wrote and delivered a long poem in Greek, which, although he did not win, amazed the audience, proving that despite his young age he had an incredible talent.

We know about the young Roman poet thanks to a tombstone preserved to this day. The relief shows him wearing a toga and holding a scroll in his hand. Even though he is barely a boy, it was decided to show him in clothes typical of a Roman citizen. His work is written around the boy’s figure on the tombstone. We know that the Roman died prematurely at the age of 11 years, five months and 12 days in 94 CE.

The boy was said to have died of overwork shortly after the competition. Mary Beard, an English historian, suspects that the boy may have been “forced” by his parents to work excessively on his workshop, due to the likely high income he provided for the household.

At the end of the republic period, their program developed, which included seven liberal arts (septem artes liberales), i.e.: grammar, rhetoric and dialectic (trivium) and arithmetic, geometry, astronomy and music (quadrivium) .

The greatest enthusiasm among young people was aroused by rhetoric, paving the way for a political and lawyer career. Now a new idea of a good speaker is born, who is also the carrier of moral and civic virtues; he is synonymous with comprehensive knowledge and deep wisdom.

Under the influence of conservative aristocratic circles wishing to halt the process of the Hellenization of Rome (in the II – I century BCE), Latin perfection began, and the development of native literature began (Cicero, Horace, Livius, Ovidius, Pliny, Seneca, Tacitus, Virgil).

This led to the establishment of Latin rhetorical schools. The first such school was founded in 93 BCE by Plotius Gall. Over time, they gained great popularity.

At the age of 17-18, military service began in the life of the young Roman, which, according to Polybius, was to affect only those more intellectually limited. Those “more talented” took apprenticeships, whether in the field of jurisprudence, administration or diplomacy.

An important aspect of a young man’s development was also recognizing him as a man. This step symbolized the assumption of virilis toga. Initially, there were no clear regulations regarding the age-associated with obtaining “adulthood” and to a large extent, the recognition of this mental state depended on the will of the father. Usually, it was between the ages of 14 and 17. It was only during the Empire that the age of majority was 16. The ceremony was held on March 17 in Liberalia, when before the lares the young man put on a bull and praetexta gown often called insignia pueritiae , to then dress the above-mentioned toga virilis in a style appropriate to the particular social layer.

Education and upbringing during the empire period |

|

However, school is not all the education of a future young Roman. In addition to the classes we call compulsory, there were also various youth organizations. Belonging to them was voluntary. In Italy, they were called Iuvenes, while in the provinces they were called Iuventus or Collegium iuventutis. In these places, young people broadened their education and developed physical fitness. Such Iuvenes was headed by praefectus or curator.

Studies in rhetorical schools

Studies in rhetorical schools began with the development of short public speeches on moral and legal topics. Later in the study, detailed literary works were read, mainly Greek and Latin poets, which contributed to the deepening of general knowledge. An in-depth study of literature was a great opportunity to master examples of beautiful phrases, expressions, and metaphors. Literary studies were very useful in composing original speeches on various topics.

It began with advisory speeches, including considerations – what to do in difficult political, social, moral, etc. situations (gathering and presenting arguments “for” and “against”). Then they went to prosecution and defence. We completed education on arranging various types of panegyric speeches (praise, praising, usually overly many people or events). Formal topics were also discussed. For example, it was agreed on what the introduction to the speech should look like, how the main goal of the speech should be presented, how to choose arguments for and against, how to praise and condemn an act or perpetrator, and how to weave quotes, e.g. from literature, and finally – how to give a speech; when to frown, when to speak quietly, when emphatically, and even screaming, when to finally tug hair and even scratch the face to effectively influence listeners.

The length of study time depended on the student’s ability and the teacher’s skills, which were often seasoned lawyers. Most often they lasted about 3 years and ended around 19-20 years of age.

A new educational ideal was born. The place for a good farmer, citizen and soldier was taken by an appropriately educated civil servant: fluent in Latin and Greek, having the ability to express his thoughts beautifully, familiar with the law and history of the state, as well as all current problems of public life, characterized by deep culture and personal grace, knowledge of human nature, common sense and good memory, a passion for practical matters, and above all, certain moral qualities.

All this meant that the attitude of Roman emperors to education, and especially to general and rhetorical high schools, was generally very positive. Emperor August put a lot of effort into the reconstruction of the Alexandria Museum; Vespasian, founded a large library in Rome, set a fixed salary for one Greek and Latin rhetoric teacher (Quintilian got it) and exempted teachers of this subject from city taxes and military service; Hadrian founded the Capitol of Rome at the Capitol, which became a meeting place for scholars and a centre of higher education; Antonius Pius extended Vespasian’s ordinance and ordered that each provincial capital keep 10 doctors and 5 teachers of rhetoric and grammar from the state treasury; medium cities – 7 doctors and 4 teachers of rhetoric and grammar, the smallest – 5 doctors and 3 teachers of grammar and rhetoric. Thanks to this, the entire secondary education system of public institutions was created throughout the empire. Other rulers of the Roman Empire had similar merits.

Roman pedagogical thought

Unlike the Greeks, the Romans did not like delving into the theoretical issues of education. They did not develop the original pedagogical theory. But the notes about education scattered around various writings show that they were able to concisely teach many practical pedagogical principles.

Cato the Elder (234-149 BCE) in Praecepta ad filium presents an ancient Roman attitude of strictness in education and simplicity of morals, which was adhered to in the early period of the republic. Marcus Tullius Cicero (106-43 BCE) made a lot of apt maxims about education in his writings. The philosopher Lucius Seneca (5 BCE – 65 CE) instructed: “a long way through the rules, a short way through the examples” (Longum est iter per praecepta, breve et efficacx per exempla); he also regretted the useless knowledge provided by the school, detached from the needs of practical life: “we do not learn for life, but for school” (non vitae, sed scholea discimus); Pliny the Younger (61-114 CE) coined the principle: “not much but thoroughly” (multam, non multa); satirist Decimus Iunius Juvenalis (60-127 CE) wrote: “a healthy spirit in a healthy body.”

Marcus Fabius Quintilian (35-95 CE) – Instituto Oratoria, which, although not too many original thoughts, was a perfect generalization of the entire upbringing practice of ancient Rome. The quintile was from Spain, from an old teacher’s family (father and grandfather were teachers). He graduated from Rome. He returned to Spain and was a teacher of rhetoric for several years. In 68 CE (at the age of 33) he moved to Rome, where in addition to teaching, he was a lawyer. Emperor Vespasian, in recognition of his pedagogical artistry, awarded him a salary from the treasury as the first rhetoric teacher in Rome. After 20 years of work, he retired and during this time, free from other activities, he began to write his work (around 90 CE). He mainly dealt with practical didactics, a way of educating a speaker who, in the author’s view, in many respects resembles a sage-philosopher according to Plato’s model.

He was to have the highest moral qualities and comprehensive knowledge; be an expert on the entire cultural heritage of humanity as well as an experienced political activist. In order to raise such a young man, he had to be looked after with care.

Quintilian was optimistic about the human developmental potential. He believed that everyone was gifted enough to learn. Like a bird, it is prepared to fly, like a horse to run, so a child to learn. There are not many people who are incapable in this respect as physically disabled, and there are no people whose educational effort would not affect them at all.

Learning abilities increase over the years and the body develops. That is why teachers and educators should be chosen with great caution – starting from the nanny. All people involved in education should have a high moral level and careful language education. The learning of preschool children should be as close to playing as possible.

Every achievement of a child should be rewarded with praise, and overcoming difficulties should be encouraged by raising ambition. He excluded all coercion and harsh treatment of children. You should not put too many demands on them. By approving the habit of educating children at home at the elementary level in wealthy homes, he opposed the Quintilian to a more general tendency to raise children at home, especially in high school.

When learning to read, do not urge boys to continue or speed in reading until they combine letters smoothly and without thinking about their meaning. Only then should they start to make words from the syllables themselves and to combine sentences with words. (…) Therefore, reading must be first and foremost reliable, then continuous and long enough slow, namely until complete correctness and proficiency reach through the exercise. [In order to] improve speech organs and clearer pronunciations, certain words and poems, intentionally difficult to pronounce, tied together in a chain of very hard-to-connect syllables should be given to boys to repeat them over and over as soon as possible. They are called Greek bits. The thing (…) hardly deserves to be mentioned, but when you miss it, many defects in pronunciation (…) remain forever as an evil that cannot be corrected later.

– Quintilian , Institutio Oratoria

He sought to completely overcome prejudices against the public school. His opponents raised mainly two issues: that a public school by educates children from different families, with different moral levels, can have a demoralizing effect on boys raised at home in the spirit of the highest ethical principles and that a student, having a private teacher at his disposal, develops much faster and more comprehensively because the educator’s entire attention is focused solely on him; the teacher also easily adapts to his individual interests.

Quintilian arguing with these allegations, admitted that sometimes the school actually demoralises the young boy, but these cases are rather unique.

However, it happens more often than the child is subject to the demoralizing influence of a poorly selected teacher, and sometimes also under the influence of parents willing to spoil them, too lenient treatment of their faults and fools, to use in their presence the wrong expressions and to lead a light lifestyle.

Quintilian disagrees with the statement that a child raised at home gains knowledge more easily. In his opinion, all ambitious and really talented teachers shun work in private homes because they feel better surrounded by more students. In addition, educating a boy at home requires more time and effort than at school. Here, the boy learns using not only the teacher’s knowledge and tips, but also the answers of his colleagues, and even their mistakes and failures.

A talented and ambitious teacher, with many students under their care, usually gets more mental and didactic effort than when he is responsible for only one boy. In addition, “The voice of a lecturer is not like a dinner which will only suffice for a limited number; it is like the sun which distributes the same quantity of light and heat to all of us. So too with the teacher of literature. Whether he speaks of style or expounds difficult passages, explain stories or paraphrase poems, everyone who hears him will profit by his teaching”.

A talented teacher can easily teach a larger group of children, paying special attention to the less able and weak, and the most talented giving only the occasional guidance necessary and stimulating their ambition to further efforts. The benefits of collective learning in a public school are also:

- that the future speaker will have to constantly appear in front of a large group of listeners and live in front of the whole society, which he will not be accustomed to learning at home, and the public school will accustom him from an early age of life to a permanent presence in a larger team;

- that a school bench creates friendships that bring people together for life;

- that a public school awakens an ambition that stimulates study and competition, but can only be developed in the company of classmates;

- that more students also stimulate the teacher to work more zealously, enabling him to extract more energy and enthusiasm.

I am not however so blind to differences of age as to think that the very young should be forced on prematurely or given real work to do. Above all things we must take care that the child, who is not yet old enough to love his studies, does not come to hate them and dread the bitterness that he has once tasted, even when the years of infancy are left behind. His studies must be made an amusement: he must be questioned and praised and taught to rejoice when he has done well; sometimes too, when he refuses instruction, it should be given to some other to excite his envy, at times also he must be engaged in competition and should be allowed to believe himself successful more often than not, while he should be encouraged to do his best by such rewards as may appeal to his tender years.

– Quintilian , Institutes of Oratory, I

Quintilian’s argumentation contributed to the victory of the idea of collective teaching in Rome, especially since the high fees for hiring private teachers made individual teaching too costly.

Quintilian’s other pedagogical observations are also worth emphasizing. He believed that the mental strength of the child (student) is so abundant that they can not be content with just one science; while looking at one object, they look in different directions at the same time. This enables them to learn more at the same time. Changing the type of intellectual employment is not only an obstacle, but it is simply a stimulus for thinking. Getting to the new mental work – he starts it with new strength. Thanks to his natural curiosity for learning, the child does not get tired and does not like to look at what he has done, but curiosity pushes them still to what is new.

Quintilian completely condemned physical punishments. He considered them to be abusive. They humiliate human dignity and are the most serious insult. The whole society must react against a weak and vulnerable age, and therefore there should not be too much freedom for the teacher in this regard. “Even if,” he asked, “some small boys can be forced to change their behaviour with sticks, what are the arguments that will have to influence them when they grow up?”

So you have to be careful about the teacher’s character, that he doesn’t hurt the student, and that he knows how to control himself and the student’s developing temperament. Quintilian’s work “Institutio Oratoria” played a very important role in the history of education, not only in Roman times. After the discovery of his manuscript in 1416, it became a model for humanistic education in Europe in the 15th and 16th centuries. Polish pedagogical writers of the Renaissance also used his instructions generously.