Chapters

Emeralds were the most popular gemstones of ancient Rome. All kinds of jewelry were decorated with them, as well as everyday objects, such as safety pins or hairpins.

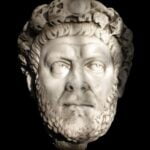

There is a well-known story described by Pliny the Elder about the passion of Nero to look at gladiator fights through a concave emerald eye that compensated for his nearsightedness and protected him from the sun’s rays. Emeralds, worn mainly by Roman women, began to be known when the Romans established contacts with civilizations outside Italy, and they spread with the conquest of all lands around the Mediterranean Sea (1st – 2nd century CE). Cleopatra also liked them very much, she decorated not only herself but also her chambers with them.

The Latin name “smaragdus” comes from the Greek “smaragdos” and means green stone. The Romans often called all green minerals emeralds, which could have caused that stones of lower hardness, not chemically, e.g. olivine, to be confused with emeralds. The only known emerald mine exploited by the Romans is the Sikait mine (also called the Emerald Mountain, and in ancient times Senskis) in Egypt, in the Wadi Sikait region in the Arabian Desert (Eastern Desert), about 45 km from the coast of the Red Sea.

Location of the mine

As mentioned above, the mine was located in Egypt, in the Arabian (Eastern) Desert, between the Nile and the coast of the Red Sea. Sikait is located 45 km from the coast, in a branch of the Wadi Gemal desert valley, sometimes called Wadi Sikait. The settlement consisted of two parts – eastern and western. Excavations in 2000-2003 showed Sikait to be 560 meters north to south and 270 meters west to east. Within the above distances, 150-200 visible archaeological structures have been distinguished. The mine itself consisted of many not very wide mining tunnels with a depth of up to several dozen meters, in which a maximum of one person could fit. Emerald is a variety of beryl, a mineral belonging to the group of silicates, with a green colour, which is due to the presence of chromium ions, less often vanadium and iron. In nature, it occurs in metamorphic rocks (mica shales, metamorphosed limestones), in granites and in sands and gravels of secondary deposits. In Sikait, mostly layers of soft mica schist were mined, where only the admixture of chromium was responsible for the green colour of the emerald.

History

The first information about the existence of the mine in the Emerald Mountain is provided by the geographer Strabo (Geography 17.1.45), mentioning its Ptolemaic origin, so perhaps not only Cleopatra had a passion for emeralds, but also her ancestors from the Hellenistic dynasty. However, it is impossible to precisely determine the date or even the century in which the mine began to operate. Pliny the Elder also writes about Sikait (Natural History 37.17.65, 37.18.69), on the occasion of discussing the 12 types of emeralds and possible damage to precious stones. As mentioned above, the Romans tended to confuse the emerald with other green precious stones, but in the case of the Emerald Mountain mine, we are dealing with real emeralds in terms of chemistry. Another author writing about the mine is Claudius Ptolemy (Geography 4.5.8) in the 1st century CE and Bishop Epiphanius (De Gemmis 40V and 88R) in the 4th century CE. The last source from Roman times is the request of Olympiodorus of Thebes from 421 CE. o visit the mine to the chief of the Blemii tribe. In the 5th century CE, the mine was thus already managed by nomadic Nubian tribes.

Probably the Empire in times of crisis was unable to maintain its control over the profitable mining industry. After the fall of the Empire, he mentions the mine in the 6th century CE. Byzantine monk Cosmas Indikopleustes (Christian topography, 11.339), so emerald mining must have continued well into Byzantine times. It is also difficult to determine how long the mine operated in the Middle Ages, for sure the discovery of America and the import of high-quality emeralds from Colombia made mining unprofitable. For modern times, the mine was discovered in 1816 by Frenchman Frédéric Cailliaud while searching for a sulfur mine in an expedition organized by the then-king of Egypt, Muhammed Ali Pasha. Since the 1990s and in the 21st century, the area of the Sikait mining estate has been intensively studied, also by Polish archaeologists.

Function – new discoveries

Archaeological research at Sikait in recent years has confirmed the religious importance of emerald mining. Although the mine operated also in Christian times, the cult of Horus was popular. Evidence was also found that the stone production process was very complicated, divided into several phases, and the mine in Emerald Mountain was perfectly organized. What needs to be clarified in the course of further research is how the process of trading and exporting precious stones to the Empire looked like, as well as when and how the Romans lost control over the mines to the nomadic Blemii.

Other sources of emeralds in the Roman Empire

Although the Emerald Mountain was most likely the main source of emeralds in the Roman Empire, they were also imported from other sources. These were India, Scythia (probably from an unspecified location in present-day Russia) and Bactria. There is also a hypothesis that a second emerald mine operated in the lands subject to Rome. Its location is today’s Austria – the Habachtal mine near Salzburg. Oxygen isotope studies in emeralds from some surviving pieces of Roman jewelry seem to confirm their Austrian origin. There are, however, no other unambiguous evidence and written sources. However, the importance of Sikait in the dissemination of precious stones in antiquity and their advantage on the Roman market is indisputable.