Chapters

Senatus consultum ultimum1, or “final decree of the Senate”, was an extraordinary resolution adopted by the Roman Senate in the event of a significant threat to the state. This term took shape during the late republic and was intended to inform high officials of Rome of the existing danger.

Traces of the term should be sought in the early days of the republic, when the dictator office was created – an official with special prerogatives who was supposed to lead the Roman state out of the crisis. The Senate, by virtue of senatus consultum, allowed consuls to appoint a dictator who gathered great power (magnum empire) until the danger is resolved or the period of 6 months has passed.

Senatus consultum ultimum appeared in the late 2nd century BCE, replacing an earlier decree of the Senate. According to Cicero senatus consultum ultimum imposed on consuls the duty to “ensure that the republic does not suffer any damage” (ut videret, ne quid res publica detrimenti caperet). The resolution uses the words: consules darent operam ne quid detrimenti res publica caperet or videant consules ne res publica detrimenti capiat, meaning “the consuls should see to it that the state receive no harm”. However, it cannot be denied that already in ancient Rome the interpretation of this provision was assessed differently because it violated applicable laws.

Use cases of senatus consultum ultimum

For the first time, senatus consultum ultimum demanded, according to Plutarch, Pontifex Maximus Scipio Nasica against Tiberius Gracchus, who was re-elected the tribune of the people. Finally, the ruling consul Publius Mucius Scevola refused this year. Scipio Nasica shouted: qui rem publicam salvam esse vult, me sequatur, or “let every man who wishes the republic to be safe, follow me!”. As a result of the confrontation, Tiberius Gracchus died in 133 BCE, and his reforms (including the implementation of the law on the division of public land) were blocked.

The first application of senatus consultum ultimum took place in 121 BCE, when, pursuant to a resolution, Gaius Gracchus’s tribune and his supporters were sentenced to execution without trial and without defense. Thus, the Senate resolution violated the existing law lex Valeria and lex Porcia. Liberal reforms (especially the proposal to grant Roman citizenship to Italian allies) Gaius did not like the patricians and, anticipating the death penalty, decided to die from the hand of his slave.

The consul Lucius Optimus, who was in court and had to prove that he did not go too far in exercising his power (imperium), was directly responsible for the decision to issue a sentence on Gaius Gracchus’ supporters. Apparently, the direct reason for the decision to use the senate’s glory was the killing of one of his helpers on the streets of the city during the rivalry of hostile camps – populares and optimates. According to Cicero, Optimus confessed that he broke the law (he was accused of quod indemnatos cives in carcerem coniecisset, or “”for imprisoning a citizen without trial”), but said he did it pursuant to senatus consultum ultimum. Eventually, the Roman was acquitted and the resolution of the senate became an unwritten law included in the achievements of the fathers (mos maiorum).

Another use case of senatus consultum ultimum was 100 BCE when Gaius Marius – 6 times consul – was asked to intervene because of fights in the city streets that broke out among supporters of populares and optimates. One of the supporters of Gaius Marius, Lucius Apuleius Saturninus – a tribune of the people – “pushed through” the Gracchi reforms, against which the Senate and its supporters stood. There were chaos and bloody rivalry between the parties in the city. Gaius Marius finally decided to intervene and closed the initiators of the reform in Curia Hostilia wanting to debate and resolve the dispute. Ultimately, however, a furious crowd lynched the deaths of the popular.

In 77 BCE Marcus Emilius Ledipus was sent by the senate to manage the province of Transalpine Gaul because the city was in a dangerous competition between the populares and the optimates. Last year he was a consul with Quintus Lutatius Catullus, which often led to their rivalry. Ultimately Lepidus returned at the head of the troops and supporters, wanting to support the popular. The Senate finally announced senatus consultum ultimum.

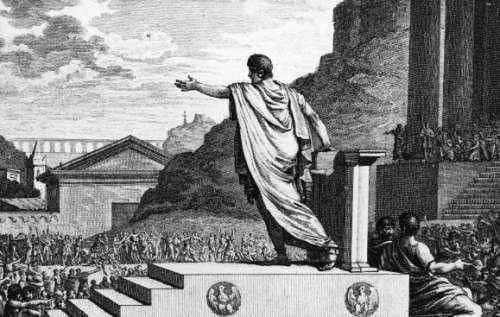

Another case of using the “final resolution of the Senate” was in 63 BCE, when the Senate was against Lucius Sergius Catiline, who wanted to commit a coup d’état. By virtue of a Senate resolution – senatus consultum ultimum – consul Cicero gave four speeches and the conspirators were executed by suffocation.

In 52 BCE, when the populist leader Publius Clodius Pulcher was killed in a clash with supporters of optimates, there was a competition on the streets of Rome, which was aroused by the tribunes and allies of Pulcher: Q. Pompeius Rufus, T. Munatius Plancus and C. Sallustius Crispus. The Senate adopted senatus consultum ultimum, two days after the assassination of Pulcher, the newly elected consul Gneaus Pompeius did not have to intervene because the riots ceased.

In 49 BCE, the senate voted to take away Julius Caesar’s command of the army and return to Rome. Negotiations took place between supporters of Caesar and the senate. As a result of the disagreement, the Senate tried again to vote against Caesar, but two tribunes spoke against the resolution. In this situation, the Senate, in order to break the voice of the opposition, adopted senatus consultum ultimum and thus recognized Caesar as an enemy of the state (hostis). Upon hearing this, Caesar crossed Rubicon, arguing that even Sulla did not object decisions of the folk tribunes.

Other use cases senatus consultum ultimum:

- in 87 BCE against Lucius Cornelius Cinna

- in 62 BCE against Quintus Cecilius Metellus Nepos and Caesar;

- in 48 BCE against Marcus Cecilius Rufus

- in 47 BCE against Publius Cornelius Dolabella

- in 40 BCE against Salvidienus Rufus

To sum up, the resolution senatus consultum ultimum enabled consuls to assume almost dictatorial power, which allowed, inter alia, to suspend the operation of certain offices/institutions. In the sources, 13 cases of senatus consultum ultimum have been passed.