Chapters

Battle of Munda (45 BCE) was the last episode of the war between the Romans. Eventually, Caesar’s absolute domination in Roman politics was established and the anti-Caesarian opposition virtually disappeared.

Historical background

After the defeat of Afranius and Petreius, Qu. Cassius Longinus. Due to his unpleasant character and great greed, he earned the hatred of the provincial population. These moods also prevailed among the legionaries subordinate to him. An unsuccessful attempt was made on Longinus, and he eventually fled Spain. During a voyage by sea, he drowned along with a ship laden with loot.

Caesar had known about the antics of Longinus in advance and dismissed him from office. However, this did not change the huge decline in support for Caesarians in the province, and many people openly switched to the Pompeian side. Besides, after Caesar’s victory at Thapsus in 46 BCE, some Pompeians who survived the pogrom have just fled to Spain. Labienus soon arrived, and brothers Sextus and Gnaeus, sons of Pompey the Great.

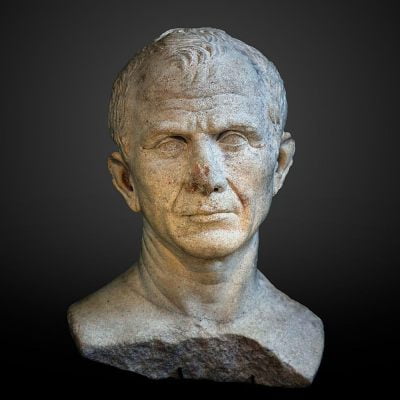

Caesar initially downplayed the emerging threat to his rule in Spain, hoping that the intervention of his legates would suffice to tame the Pompeians. However, at the end of 46 BCE, he understood the scale of the problem himself and went to Further Spain. Thirteen legions stood against his army, supported by many auxiliary units. Their commander, Gnaeus Pompey, despite his determination, did not sin with military talents, and his legions did not have full manpower. The forces of Caesar are estimated at 8 legions, of which only V Alaudae and his beloved X Legion had experience on the battlefield. In addition, some of the legionaries from these units have retired. Therefore, there was a fear that, despite the many victories he had previously won, Caesar might succumb to his enemies.

Battle of Munda

We learn about this clash from the Spanish War, written by Caesar’s subordinate. However, this book does not contain many details, so historians only have a brief summary of these events. When Caesar arrived in these areas, the siege of Ulia had lasted for several months, the only one of the larger centres that remained loyal to him. Caesar besieged Corduba, the provincial capital, in order to draw the enemy away from this city. The defence of this centre was led by Sextus Pompey, who soon persuaded his brother to withdraw the legions from Ulia. Gnaeus tried to harass Caesar’s army besieging Córduba, but he did not allow himself to undertake a major battle. Caesar, seeing the impossibility and futility of further blocking Corduba, set off for the city of Ategua. When the winner from Alesia successfully stormed the city and many residents wanted to capitulate, the garrison commander led all suspects of surrender outside its walls and killed them and their families. When the Pompeians’ hope for relief failed, it was decided to open the gates to Caesar on February 19, 45 BCE. Following them, more cities surrendered to Caesar, and more and more Pompeian legionaries deserted.

The actions of both sides in this war were characterized by cruelty. Gnaeus, in response to the desertions of his subordinates, was sentenced to death all suspected of similar attitudes. In late February, Caesar’s men captured four scouts, three of whom were crucified and the fourth was beheaded as a legionary. Caesar followed the retreating enemy until they reached Urso. The Pompeians camped 10 kilometres from the city, on a hill near Munda. Pompeian legions did not have full personnel, which was caused by the delegation of some soldiers to garrisons and losses during hostilities. Caesar placed his army on the plain in front of the enemy, which placed him in a less favourable starting position. Initially, he believed that the confident Pompeian legionaries would descend to the plain, however, they did not abandon their positions on the rise. Caesar decided to attack up the hill, trusting in his luck and the attitude of the soldiers eagerly awaiting the clash. The right-wing was traditionally taken by the 10th legion, the left legions by the 5th and 3rd legions. The rest of the army, made up of five legions, formed the centre of the formation. The Caesarians were the first to fight – the Pompeians initially took a passive stance, only at the last moment they counterattacked. The beginning of the battle did not herald Caesar’s victory – at some point, his battle line began to break down. Thanks to the attitude of the chief, who noticed the danger in time and rushed to the endangered places, the situation of the Caesarians began to return to normal. When Caesar got close to enemy lines, he had to huddle under his missiles or protect himself with a shield. Officers soon joined him, followed by legionaries. Plutarch quotes the chieftain’s own words that he was to say that he had fought many times before in this battle – for the first time for his life. When the X Legion breached the enemy’s left flank, Labienus tried unsuccessfully to intervene with one legion. The Caesarian cavalry took the opportunity to crash onto the flank and rear of the Pompeians. The latter ones could not stand it and their ranks collapsed. Despite his victory, Caesar’s losses were significant – 1,000 men. The number of killed enemies, 33,000, is rather exaggerated.

The importance of the battle

The Battle of Munda was the last episode of the war between the Romans. Eventually, Caesar’s absolute domination in Roman politics was established and the anti-Caesarian opposition virtually disappeared. Labienus was killed at Munda, and the wounded Gnaeus Pompey was captured after a few weeks and beheaded. The victorious Caesar was awarded the title of Liberator and Emperor, had a great triumph, and the scope of his power continued to expand.

The Battle of Munda did not immediately foreshadow Caesar’s victory. His soldiers, most of them poorly experienced, initially succumbed to the enemy’s onslaught, which could have ended in defeat. The decisive attitude of the leader, who knew how to react in the threatened section, and the experience of the legions from the right-wing ensured victory for Caesar.