Ancient Romans caught wild animals mainly for the needs of organized games and hunting in amphitheatres (the so-called venationes). Exotic animals were imported from many lands and provinces, and most often caught by natives who were familiar with their trade and the surrounding area.

Africa was the main source of animal supplies, from where hippos, lions, elephants, giraffes, rhinos and leopards were imported. Tigers were brought from India; interestingly, research1 indicates that tigers were not only caught in India but also in Armenia. From there they were transported by sea. Bears, deer, wild boars were transported from northern and central Europe.

The lions, whose fight in Rome was for the first time organized by Quintus Scaevola during his role as aedile in 95 BCE. Praetor Sulla in 93 BCE brought as many as a hundred lions into the arena. Pompey the Great organized the games at which 600 predatory cats appeared, then Julius Caesar showed 400 animals on his spectacle.

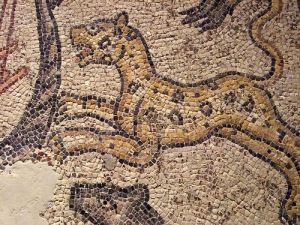

The lions themselves were caught by arranging traps by digging appropriate pits. The Greek observer Oppian (2nd-century Roman poet) mentions this. The dug pit was adequately covered by a camouflaged surrounding wall. A stake with a lamb’s body protruded from below. When a lured lion jumped down, the hunters locked the animal in a cage.

Another way was to lead the frightened lion by hitting the shields by the armoured riders to make him fall into the nets set by hunters. The hunters also dressed in sheep’s clothing and focused the attention of the lion one by one. Exhausted from constantly running after the victims and the confused, the animal was then captured.

Pliny the Elder also gives a way to tame an animal, “unworthy” of the majesty of a lion. A shepherd from Getulia, quite by accident, imposed a big tomcat over its head, which effectively calmed the beast. This method was quickly transferred to the arena. As Pliny, himself notes: “Apparently all its [lion] strength is in sight”.

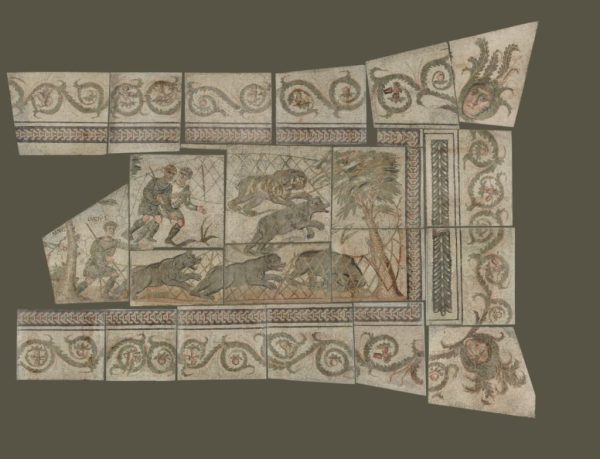

Hunters, hunting for tigers, avoided direct confrontation and usually caught a wild cat when it was young. A trick was used to steal little tigers from the den. The hunter on horseback headed for the ship, knowing that the mother would certainly follow her young. As soon as the tigress approached the horseman, he released the cubs, which the mother then carried back to the den. When the tigress caught up with the hunter again, he released the second tiger. In this way, the hunter reached a safe place or ship and was able to deliver to the amphitheatres the young tiger. Another way to distract the pursuing tigress was to drop the mirror; the female watched her reflection, thinking that it was her young.

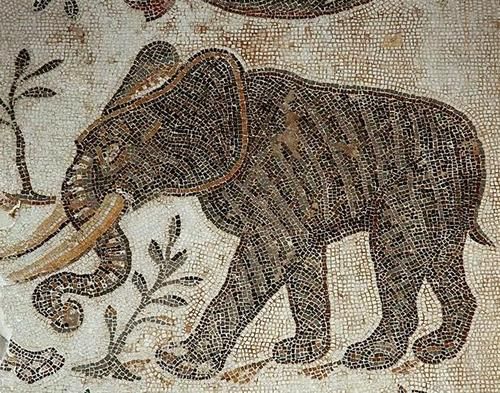

A special attraction were elephants, which Romans met at the beginning of the 3rd century BCE, during the war with Pyrrhus, king of Epirus, and then in 250 BCE during the conflict with Carthaginians. At that time, the Romans gained 140 animals on the Carthaginians after the victory of Lucius Metellus Pontifex in Sicily. Pliny the Elder mentions in his encyclopedic work “Natural History” that a herd of elephants surrounded by hunters are positioned so that the individuals with the smallest tusks are in front. In this way, they supposedly want to convince people that it is not worth applying for ivory. When the animals are exhausted by fighting, they break their tusks by hitting the trees. In this way they save lives, leaving precious prey to hunters. As for the elephants, they were first admired in the amphitheatre in Rome in 99 BCE.

Pliny also gives ways of catching animals in India and Africa and their cooperation in the herd:

In India they are caught by the keeper guiding one of the tame elephants towards a wild one which he has found alone or has separated from the herd; upon which he beats it, and when it is fatigued mounts and manages it just the same way as the other. In Africa they take them in pit-falls; but as soon as an elephant gets into one, the others immediately collect boughs of trees and pile up heaps of earth, so as to form a mound, and then endeavour with all their might to drag it out. It was formerly the practice to tame them by driving the herds with horsemen into a narrow defile, artificially made in such a way as to deceive them by its length; and when thus enclosed by means of steep banks and trenches, they were rendered tame by the effects of hunger; as a proof of which, they would quietly take a branch that was extended to them by one of the men.

– Pliny the Elder, Natural History, VIII.8

Naturally, hunters also used much more brutal methods to force elephants to comply:

At the present day, when we take them for the sake of their tusks, we throw darts at their feet, which are in general the most tender part of their body. The Troglodytæ, who inhabit the confines of Ethiopia, and who live entirely on the flesh of elephants procured by the chase, climb the trees which lie near the paths through which these animals usually pass. Here they keep a watch, and look out for the one which comes last in the train; leaping down upon its haunches, they seize its tail with the left hand, and fix their feet firmly upon the left thigh. Hanging down in this manner, the man, with his right hand, hamstrings the animal on one side, with a very sharp hatchet. The elephant’s pace being retarded by the wound, he cuts the tendons of the other ham, and then makes his escape; all of which is done with the very greatest celerity. Others, again, employ a much safer, though less certain method; they fix in the ground, at considerable intervals, very large bows upon the stretch; these are kept steady by young men remarkable for their strength, while others, exerting themselves with equal efforts, bend them, and so wound the animals as they pass by, and afterwards trace them by their blood. The female elephant is much more timid by nature than the male.

– Pliny the Elder, Natural History, VIII.8

Most often, elephants were hunted by hunters in such a way that they fell into the hole; leopards, in turn, were hunted with the help of burning torches by a group of armoured horsemen.

Soldiers were also used to capture wild animals. Often, men from local areas got into the army, who were specialists in catching and hunting the wild beast there. For example, we know a certain Cessonius Ammausius, a soldier of the XXX legion stationed next to the Rhine, who referred to himself as ursarius – archaeologists translate it as “bear hunter”. In Cologne (Germany) an inscription was found mentioning the capture of 50 bears in six months by one of the hunters.