Chapters

The trial of Gaius Verres, governor of Sicily for fraud in 70 BCE is the best described and source-presented event showing the degree of corruption of Roman officials and the use of the provinces for their own selfish needs and the desire to get rich.

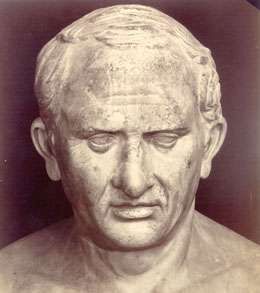

The main source of information about Verres himself and the trial come from the preserved letters and accusatory speeches of Cicero. No notes or notes have survived from the defense side. Naturally, this raises the suspicion of a one-sided depiction of history, but even ignoring many of Cicero’s dubious claims, it is certain that Verres was an example of a man corrupt and exploiting the inhabitants of Sicily on a large scale.

Who was Gaius Verres?

Gaius Verres was born around 114 BCE into a senatorial family. According to Cicero, Verres’s father could also “boast” about corrupt activities, but not on the scale of his son. We don’t have any information about Verres’s mother. The young aristocrat, certainly like other well-born people, went through the next levels of education. He reportedly showed a willingness to indulge in debauchery. Probably also in his adolescence, his admiration for art arose in him, which during his governorship turned into a real obsession.

Career

Verres’s first office was quaestor, in 84 BCE. Stationed with consul Papirius Carbon’s troops in Gaul, he probably embezzled hundreds of thousands of sesterces; leaving office in 82 BCE.

In 81 BCE Verres was appointed legate of Cornelius Dolabella, governor of Cilicia. The new position made it easier for Verres to “acquire” works of art (statues and paintings), incl. from the temples. At that time, the need to get women also arose in him, even though he already had a wife. While in the city, Lampsacus commissioned his assistants to find out if there was any interesting “virgin” in the area that would make Verres stay in the city for longer. One of his charges – Rubrius – informed you that there is a beautiful young girl in the area who lives with her father – Philodamus, the local representative of the elite – in the mansion. During one of the feasts at Philodamus’ house, the “invited” Rubrius asked why his daughter was not feasting with them. He replied that according to Greek custom, women did not feast with men. Eventually, there was a fight in the host’s house, as a result of which Rubrius poured boiling water over Philodamus, and many of Verres’ slaves and his lictor Cornelius perished. Verres was driven out of the city and began devising a plan of revenge. He accused Philodamus and his son of killing his lictor – although they were defending their daughter’s honor – and influenced the court to convict them. Then the father and son were killed in the market Lampsacus.

Verres’s next office was bursar with Dolabella. At that time, his attention shifted to collecting additional fees on real estate and generating his wealth. Following the end of Dolabella’s office and his return to Rome in 78 BCE, an extortion lawsuit was brought. Thanks to his efficient actions, Verres avoided responsibility, directing all accusations against the governor, who had been sentenced to exile.

In 74 BCE Verres was elected praetor. Cicero accuses him of giving enormous bribes of 300,000 sesterces, which were distributed to the voting professional “bribe-takers”. While already in office, Verres increased his wealth by accepting “money gifts” for the approval of construction plans in the city. Cicero gives an example of the praetor’s bribery in the matter of repairing the temple of Castor and Pollux on the forum. Verres hoped that the repair of the building would not be successful and would, in accordance with the law, demand additional money from the contractor for failure to comply with the contract. However, to Verres’ surprise, the temple was very well repaired and there were no shortcomings in its execution. At the suggestion of one of the extortion helpers (Cicero calls them “dogs”), Verres announced that virtually every column is not perfectly perpendicular. Therefore, the praetor ordered rigorous tests to show that the columns were not perfectly vertical – it is worth adding that it was in no way required or contracted, and what’s more, it did not affect the solidity of the structure. On the pretext of refusing the execution, Verres demanded a bribe. The contractor proposed an amount of 200,000 sesterces, which was, however, rejected, and Verres commissioned the selection of a new contractor for the repair of the building. A “friendly” contractor was selected who “repaired” the “defect” shown without any problems. The repair was estimated at 560,000 sesterces, and the original contractor was appointed to cover it.

Governorship of Sicily

Sicily was an important Roman province that provided the state with enormous grain supplies and was sometimes referred to as the “storehouse of the empire”. The assumption of the governorship of Sicily by Gaius Verres in 73 BCE was a real ennoblement, and for him himself a great opportunity to enrich himself. For three years1of his reign, Verres – in line with Cicero’s speech – committed the following offenses:

- abuse of judicial powers;

- the enforcement of agricultural taxes;

- confiscation of works of art and private and public goods;

- mismanagement of the fleet and unlawful judgments.

In the case of judicial abuses, Verres showed real disrespect. He ordered to pay himself bribes if he wanted to obtain a favorable sentence; he intimidated judges during the trial and threatened them with death; falsified court records, the number of witnesses; ordered a false testimony to be made; decided about the choice of priests. Moreover, Verres ordered the Sicilian cities to set aside money to build public statues. The part of the money that was not used was transferred to the private account of the governor.

Realizing the agricultural wealth of the island, Verres decided to raise private money also from this sector of the economy. Until now, in Sicily and Sardinia, annual tithes (decumae) have been collected on crops, mainly wheat and barley, with constant values. Generally speaking, the greater the yield, the greater the portion of the harvest had to be handed over to the state. However, this system was changed after Verres, who chose a certain Apronius as the head of decumani. From now on, it was Verres’ charge who decided on the amount of the crop tax. Judges were empowered to enforce the agreed tax, under the threat of up to a fourfold increase in the tax. The result of this change was that Verres and his charges grew rich and farmers became poorer.

According to Cicero’s message, Sicilian farmers (aratores) thought they were lucky when they were not obliged to pay three times the tax they used to pay before Verres’s arrival. Some farmers were forced to supply more grain than they could produce, leading to them either fleeing the island or committing suicide. Fields were left fallow, even though they were cultivated by generations. In the district of Agyrium alone, the number of farmers fell from 250 to 80. After three years, Sicily – “Rome’s granary” – was only able to feed its own population.

The governorship of Sicily also gave Verres the chance to enrich his private art collection, which became his true obsession. During his accusatory speech, Cicero emphasized the poor taste of Verres, who had a great love for Greek instead of Roman art2.

Any Sicilian who was fortunate enough to possess a statue or painting could feel threatened. The island was full of Verres ‘dogs’ who informed the governor of interesting objects that could enrich his collection. Once at a feast with one of the Sicilians, he deprived his host of a beautiful silver tray on which the dishes were served. Moreover, one day Verres, while in the city of Haluntium, ordered all the distinguished inhabitants to collect all their objects made of silver or Corinthian bronze, and then send them to the sea, where Verres was to evaluate them. Decorated elements (emblem) were removed from works of art, and looted objects were returned to their owners with symbolic amounts. The ornaments obtained in this way were then passed on to artists in Syracuse, who attached them to selected objects by Verres.

One of the victims of Verres’ greed was a man named Heius who owned one of the most beautiful houses in Messana. His villa – in the opinion of Cicero – was considered a tourist attraction. On the property, there was a sanctuary with four beautiful statues: a marble Cupid that once adorned the forum in Rome, a bronze statue of Hercules, and two others. Verres took from Heius his works of art, in return paying him ridiculous money (6,500 sesterces) and imitating the purchase. The wealthy Sicilian, however, did not want money, as no amount could replace his loss of statues. Consequently, he brought a lawsuit which, as could be expected, did not allow him to recover the items.

Verres’ next victims were the princes of Syria, who in 73 BCE were on their way from Rome to Syria to assume the throne of his deceased father. They stopped in Sicily because Verres decided to “host” them in his beautiful palace. The governor noticed a beautiful candelabrum made of gold, which he soon “found” in his hands. Syrian princes, demanding the return of the item, received a response that Verres treats the object as a gift from them, and they themselves must leave the island as soon as possible, as pirates from Syria have set off towards them.

There was no end to tricks and ways to loot valuable property. Verres tried in every possible way to become the owner of the selected work of art. Not only private owners were robbed, but also public property: incl. the temple of Minerva was stripped of wooden panels depicting the battle scene, doors made of gold and ivory, large bamboo spears, and the head of a Gorgon. Statues disappeared from forums and sanctuaries. All the looted works of art were stored by Verres in his warehouse on the Messana wharf, where he admired the accumulated wealth.

Another offense Cicero felt by Verres was the incompetent management of the naval fleet, which was unable to resist the pirates. Poorly chosen command and wrong decisions caused the Sicilian ships to fall prey and the population to be captured. To avoid responsibility, Verres accused the fleet admirals who had been sentenced to death.

Finally, Cicero emphasized the cruelty of the rule of Verres, citing the story of the merchant Servilius of Panormus. This caught the governor’s attention when he publicly criticized the administrative scandals in Sicily. In return, Verres charged him with illegally seizing property belonging to the goddess Venus. Servilius pleaded not guilty and then refused to pay a form of debt. Eventually, he was beaten by six of Verres’ lictors and died from his injuries.

The trial of Gaius Verres

Soon after Verres left Sicily in 71 BCE, the island’s representatives arrived in Rome with an official motion against their former governor. This possibility was guaranteed by the Lex Calpurnia, established in 149 BCE. On the basis of this legal basis, the convicted official was obliged to pay 250% of the proven amount he had obtained as a result of fraud and looting.

The Sicilians also asked the famous Roman lawyer and speaker Cicero to take the position of the prosecutor in this case. It is worth adding that the inhabitants of the island remembered the senator as a good and effective quaestor from 75 BCE, who held his office in the Lilybaeum district. For 36-year-old Cicero, it was an opportunity to gain fame at the expense of his main rival in Rome – the lawyer of Hortensius – the defender of Verres.

In 70 BCE, the case against Verres was officially brought to court. The main judge was Manius Acilius Glabrio, whose person – in Cicero’s opinion – was impeccable. As his office ended on December 31, 70 BCE, the main purpose of the defense was to postpone hearings. Hortensius hoped that in the new year the judge would be a person with more corrupt inclinations. Moreover, a new prosecutor was put forward – Quintus Caecilius Niger. Under Roman law, the prosecutor was not chosen by the state, but by the flood. In order to clearly state whether Cicero or Niger would lead the case as a prosecutor, it was necessary to appear and persuade the Sicilians to pursue claims before the court – it was the so-called divinatio. On January 15, 70 BCE, Cicero gave a fiery speech in which he argued why it was he and not Niger to represent the Sicilians. In the end, Cicero’s arguments, not his rival, gained approval and Cicero officially became the prosecutor in the trial.

Cicero, already as a prosecutor, officially accused Verres of extorting 40 million sesterces during the governorship of Sicily and demanded a penalty of 100 million sesterces – according to Roman law, this was the maximum amount that could be requested. Then Cicero asked for a 110-day break, and during this time he went to Sicily, where he collected statements and evidence against Verres, which he then wanted to use during interrogations. After returning to Rome, Cicero learned that the defense had managed to postpone the trial by another 108 days during this time. Another way to defend the trial was to use procedural loopholes that would prevent Cicero from carrying out the entire “accusatory attack”. It was hoped that it would be possible to avoid a hearing by the end of the year, and then Marcus Caecilius Metellus – Verres’ supporter will most likely become the new judge.

Cicero had no choice. Finally, on August 5, the trial in the Verres case was opened. Cicero, having little time, gave up a long argument in favor of a short and spontaneous speech, and then for the next nine days, he was asking more witnesses. In this way, he managed to avoid the holiday breaks and present the entire prosecution. After just three days of deliberation, Verres “felt bad” and stopped coming to the hearings. Without waiting for the sentence, Verres went to Massalia.

After process

According to the verdict, Verres was sentenced to exile to Massalia, where he died after 27 years. Some of the valuables he had stolen went with him to southern Galli. In 43 BCE, Mark Antony demanded from Verres, now 70, the return of the Corinthian vases. The still greedy Roman refused; it cost him his life.

Cicero, in turn, leading the case and leading to the conviction of Verres, won a great victory, which allowed him to obtain the title of the greatest orator and lawyer of Rome. This event also gave him a chance to develop his political career: in CE 66 he became praetor, and in 63 BCE he became a consul. It was a great achievement for the human homo novus3.