Chapters

Battle of Magnesia was the decisive armed clash in the war between Rome and the Seleucid Empire of Antiochus III the Great. The battle was fought in December or January 190 BCE, near Magnesia ad Sipylum, on the plains of Lydia (present-day Turkey).

Situation

The rivalry between Rome and the state of Antiochus III lasted from 192 BCE and was fought for influence in the Hellenic territories. Antiochus, at the request of the Ethols, came to Greece with a small army in 192 BCE. There, however, he was defeated by twice the size of the Roman army in the Thermopylae Gorge (in 191 BCE) and sailed to Asia. The Roman navy, supported by allies (including the Rhodes), gained dominance at sea and allowed the Roman army to transfer hostilities beyond the Hellespont. After Antiochus, Consul Lucius Cornelius Scipio and his victorious brother Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus went to Asia.

The Roman army was commanded by the younger brother of Scipio Africanus the Elder – consul Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiaticus (he received this nickname – Asian – after the battle). The great victor of the from Zama was in de facto advisory role at the time as a legion of the legion, though sources say he was sick in Elaia.

It is worth mentioning that Carthaginian enemy of the Romans, Hannibal after the defeat of his troops in During the Second Punic War he took refuge at the court of Antiochus, hoping to continue his fight against Rome. Some suspect that it was under Magnesia among the Seleucid forces. However, this claim is false, because the Carthaginian commander commanded Antiochus’ fleet and, after a series of defeats, retired to Crete, fearing that Antiochus, seeking a compromise, would decide to hand him over to his opponents. Eventually, Hannibal fled to the king’s court in Bithynia.

Antiochus, expecting the invasion of the Romans, decided to choose a favourable area for the camp. He secured the approach to Sardis and the naval base at Ephesus, and waited for the enemy.

Troops of Antiochus

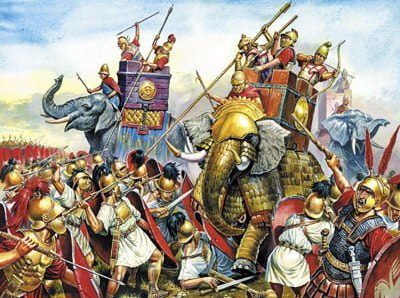

Titus Livius and Appian of Alexandria1report that Antiochus for battle fielded 16,000 hoplites sarissofori arranged – on the Macedonian model – in units (taxeis) of 1600 people each; 50 people wide and 32 people deep. There were breaks between the units, in which he placed 2 war elephants, where each animal was accompanied by 50 skirmishers. This is how Livius described the elephants of Antiochus:

[…] elephants, standing out especially conspicuously among the soldiers. They were of great size; head-armour and crests and towers placed upon their backs, and, in addition to the driver, four soldiers riding in each tower, added to their impressiveness.

– Titus Livy, Ab urbe condita, 37.40.8

According to Appian, the phalanx supported by elephants resembled a wall with towers. On both sides of the phalanx, there were 1.5 thousand Galatians from Galatia. To the left and right of them was a heavy ride – cataphracts – totalling 3,000. On the right, Silver Shields (elite infantry argyraspides) and mounted Dahs, famous for firing arrows from their bows backwards. Further on the left-wing stood Oriental infantry, 2,000 mercenaries from the son-in-law of Antiochus – Ariarathes IV, 2,700 Oriental light infantry and 1,000 excellent cavalry regia cohors, as Livius called it. At the very end of the left flank, Antiochus additionally placed 2,500 Celtic horsemen and 500 horse spearmen called tarantines in order not to get flanked.

On the front of the left flank there were about 40 four-horse war chariots, which were to shred the enemy cavalry with scythes mounted at the wheels. They were to be supported by Arab riders, who, according to Appian, sit on very tall camels and easily shoot bows from above, and when they approach the enemy, they use narrow swords. In the second line of Antiochus’ army were 32 war elephants, and in front of the main army were light-armed blasters.

Antiochus took command of the right flank, handing the left flank to his son Seleucus and his cousin Antipatra. Philip, the elephant commander, ruled in the centre. Antiochus felt respect for Roman troops, therefore he departed from the classical deployment of Hellenic troops with hoplites in the centre and riding on the sides, forming the army into a “sandbox” of infantry, cavalry and elephants.

Roman troops

When the Roman armies entered Anatolia, they were joined by the king of Pergamum – Eumenes II. The Roman army – under the command of Lucius Cornelius Scipio – together with allies totaled about 30,000 infantry and 3,000 cavalry. The Roman forces were positioned as standard: two legions in the center (5,400 men each), Latin allies on the sides (similar forces had two wings), and on the right-wing, an additional three thousand Achaean and Pergamon infantry. On the edge of both wings, there was a cavalry of the king of Pergamon, numbering 800. Summing up the cavalry of Pergamum, Romans and Italians, the army numbered 3,000 cavalry on the right-wing. Lightly armed mercenaries and velites (6,000) stood in front of the army to start the battle. The legionaries were arranged in a triple formation triplex acies – a chessboard that could be up to 3 km long. At the rear of the Roman army stood 16 elephants of Scipio, provided by an ally from Numidia, Masinissa – the Roman commander was aware of the enemy’s superiority in the number of elephants. Livy described the Roman battle line as having uniform character as to the type of people and as to weapons.

The left-wing of the Roman army was based on the bank of the Phrygios River, therefore there were only four cavalry units (turmae) in this part of the battlefield – 120 cavalry in total. The natural protection on the left side allows you to concentrate the entire ride on the right flank. Emunes went to command on the right flank; on the left wing was commanded by the legate Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus; he left the center to himself.

Both Livy and Appian agree that about 30,000 people took part in the battle on the Roman side; and Antiochus 70,000. Modern authors increase the number of Romans to 50,000.

Antiochus was outnumbered, but the Roman army was much better armed, uniform and experienced (there were many veterans of Scipio in the army). Seleucid’s disadvantage was the fact that his army had many new recruits and differed greatly in origin and equipment.

The main assault Lucius Cornelius Scipio wanted to carry out on his right flank, overcome the enemy’s seven-thousandth cavalry, and then surround the Seleucid phalanx. Antiochus made a big mistake here, concentrating large troops of hoplites in a small space, thus not using his main strength.

Battle

Scipio, a Roman commander, wanted to settle the conflict before winter before a new consul would be elected in his place, which would surely put a brake on the campaign. To this end, he marched as quickly as possible towards the army of Antiochus and set up a camp 4 km from the enemy.

The battle took place near the road from Sardis to Smyrna, between the rivers Phrygios and Hermos. Apparently, the day of the battle was misty and gloomy, and the drizzle soaked both armies and, as Livius reported, took the elasticity of bows and thongs.

The fight began with Antiochus, who hit the right-wing. The right-wing, commanded by the Seleucid king, broke through the light infantry and heavily armed Latin troops. However, instead of attacking the Roman army from behind, Antiochus chased the escapees and left the battlefield. The escaped soldiers headed towards the Roman camp, 1 km away, commanded by the military tribune Marcus Emilius Lepidus. He rebuked the fleeing legionaries, whom he had ordered to kill if they continued to flee. This worked and the Romans formed a battle line and repelled the attack of Antiochus’ cavalry, is additionally supported by the 200-man cavalry from the battlefield.

At the same time, the war chariots on the left flank set out on the enemy cavalry. Eurenes sent horse spearmen to throw missiles at chariots and horses. Under the influence of the cloud of bullets and wounds, the horses pulling the chariots fell into a panic and began to mow their own strength with scythes. The Romans took advantage of this chaos, completely eliminating the resistance on their right-wing, despite the support of the returning royal cavalry.

In the centre, the Macedonian phalanx moved to the first Roman line – hastati. The soldiers of the republic began to retreat under the pressure of a stronger enemy. Hoplites effectively prevented the Romans from fighting in a short distance, which meant that the phalanx did not suffer any losses.

Ultimately, however, the full victory of the Romans on its right flank meant that the centre of Antiochus, dominated by heavily armed infantry, had to fight from the front, side, and repel the attacks of the Roman cavalry from the rear. In addition, they were fired with bows and piled with piles. The elephants between the squads of hoplites began to panic and trample their own lines. The Romans took advantage of the disorganization and launched a frontal attack that forced the enemy to flee.

The battle ended with the complete victory of the Romans and the massacre of Antiochus’ troops. This is how Titus Livius described the slaughter at Magnesia:

But a greater peril to the fugitives, the chariots and elephants and camels being mingled with them, was the disordered mob of their own men, since their ranks once broken, as if blind they rushed one over the other or were trampled down by the charging beasts.

– Titus Livy, Ab urbe condita, 37.43.9

The fleeing infantry was trampled by Eumenes’ cavalry. The Roman infantry, in turn, moved to the hostile camp, from which it was repulsed the first time. The second time, however, the legionaries captured the camp and out of anger alone, carried out a greater massacre there.

According to Livy, about 50,000 infantrymen, 3,000 cavalry, died on the battlefield. 1,400 people and 15 elephants were taken into captivity. Appian, in turn, claimed that about 56,000 infantry, some elephants, and 15 of these animals were captured. The losses of the winners were reportedly limited to only 300 legionaries and 24 horsemen, 25 of Eumenes’ men.

The main cause of the defeat of Antiochus was the tactical mistakes he made, the use of obsolete weapons – chariots with scythes, wrong positioning of the elephants and distancing himself from the main forces. As a result of this defeat, Antiochus lost the war with Rome and had to relinquish his possessions in Asia Minor. Appian gives accusations under the direction of Antiochus:

They accused him of his latest blunder in rendering the strongest part of his army useless by its cramped position, and for putting his reliance on the promiscuous multitude of raw recruits rather than on men who had become skilled in military affairs by long training, and had been hardened by many wars to the highest state of valor and endurance.

– Appian, The Syrian Wars, 8.37

Consequences

The Romans presented Antioch with the same conditions of peace as they had set him before, but with minor changes regarding the border. He had to withdraw completely from Europe and from Asia in the previously agreed part. According to the arrangements in Apamea, the king was obliged to give up some of the important lands in Asia Minor (giving up the lands north of the Taurus Mountains – that is Thrace and almost all of Asia Minor) and to cover the war costs of 15,000 talents – about 300 tons of silver – to Rome in twelve years. Moreover, he had to hand over prisoners, fugitives, some of the ships, and all the war elephants, which he was not allowed to possess in the future.

In addition, the Romans were to choose 20 hostages for themselves (including the younger son of Antiochus), which had to be replaced every 3 years (except for the son of Antiochus). Antiochus could not recruit mercenaries in the countries under Rome’s control, nor accept fugitives. He could have only 12 ships, the number of which he could, however, increase in the event of a war in the country. The layout was engraved on bronze plaques and placed on the Capitol.

The territories conquered by the Syrian king in Asia Minor were divided between Eumenes of Pergamum and Rhodes, especially the former became the ruler of the most powerful kingdom in Asia Minor. Other immediate consequences of the defeat of the great king were perturbations in the eastern frontiers of the state, when news of the defeat of the “invincible king” reached there, the satraps raised revolts and numerous barbarian tribes began to invade the empire.

The defeat at Magnesia had very serious consequences for the world then, and especially for the Seleucid monarchy. First of all, the state of Antiochus lost its power status (at least as far as the West and Europe are concerned), since then the Syrian kings were no longer able to conduct a fully independent international policy as regards the Mediterranean basin. The Seleucid dynasty lost its former splendour forever.