We currently have a wealth of Roman materials. They are of two kinds. So we have inscriptions: on statues, stone slabs that have survived two thousand years of wars, actions of nature and devastation. Information was also obtained from pieces of bronze, dug most often in arable fields. Many factors could have contributed to the destruction of the historical evidence.

However, one of the most frequently used sources of texts is the records of people living at that time. Most often they were little-known or simple people who tried to complain and describe their difficult life situations. They presented their everyday life, love troubles, and fear for their own lives. However, there are also records that were left by soldiers or army commanders. Thanks to them, we get to know in detail what the drill, the day’s march or the construction of the camp looked like.

The inscriptions tell us about the history of people such as Gaius Mannius, a legionary from the 20th legion “Victrix”, from a village near Turin, or the life of Tiberius Maximus, an officer of the cavalry of Philippi who in 106 CE he had tracked down the escaped king of Dacia, Decebalus, just as he was about to cut his throat. Another author, Gaius Minicius, a 27-year-old colonel from Aquileia who served under Vespasian in the Civil War of 69 and won the highest Roman decoration for bravery.

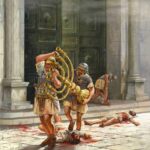

The historical writings at our disposal today are numerous and rich. Different authors describe the same event in different ways. Thus, we are not able to clearly state who is telling the truth and who is lying. Take for example the bloody death of the emperor Vitellius (he was followed by Vespasian), which has been variously reported in the writings of Plutarch, Suetonius, and Cassius Dio. None of them was eyewitnesses to this event, and each was based on other people’s stories. Another example is the attitude of Titus (son of Vespasian and commander of the Roman army in the Jewish uprising) to the destruction of a huge complex of buildings and the question of temple courtyards in Jerusalem. During the fighting, the Roman command considered whether to burn the tabernacle or keep it. Titus in Josephus (a Jewish insurgent and later writer) did not want to destroy the temple. However, an ancient writer – admittedly much later, but perhaps based on credible accounts – claims that it was Titus who sought the destruction of the temple, believing that this was the only way to break the Jewish spirit of resistance once and for all. So, as you can see, one cannot blindly trust the accounts of one historian. Be objective and try to present the most balanced, yet broadest view of the matter.

The history of Rome is very long, dating back from 753 BCE to 476 CE, not including the history of the Byzantine Empire, which was formally part of the Empire until 1453. The trustworthy history of Rome begins only in 280 BCE when the Greeks began to be interested in the history of the Romans. Historiography also became a passion for the Romans, who, especially in the 1st century CE created numerous works. As you can see, when trying to explore the true version of history, to understand what events really took place in the past, we must rely on the sometimes unreliable works of Roman and Greek historians; personal notes or other types of historical sources. We need to objectively look at the works of such historians as: Plutarch, Suetonius, Dio, Tacitus, Josephus, Livius, and Pliny the Elder and the Younger.