Chapters

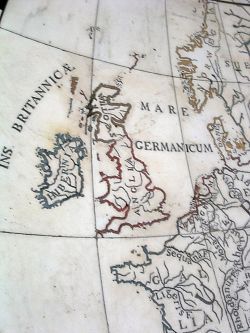

The name Britannia was used by the Romans to refer to the two largest British Isles. Another name the Romans gave to Britain was Insula Albionum. Today’s Great Britain was referred to as Britannia Maior (Greater Britain), while today’s Ireland was referred to as Britannia Hibernia (Hibernia).

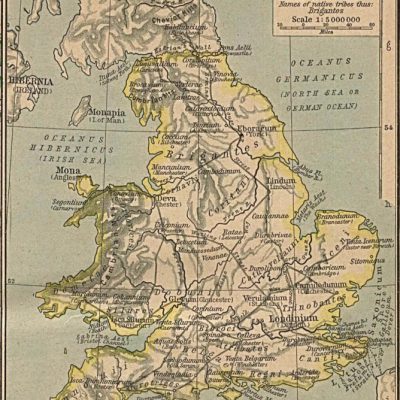

Britain in Roman times was inhabited mainly by Celtic people, Britons in what is now England and Wales, Scots in Ireland, and non-Indo-European Picts in what is now Scotland.

The town of Verulamium, located in what is now the city of St Albans in Hertfordshire, England (United Kingdom) and situated on the River Ver, was the largest next to Londinium a Roman centre in Britain and from c. 60 CE the capital (municipium) of the Roman province of Britain.

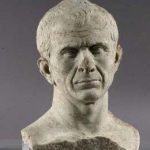

Gaius Julius Caesar attempted to subjugate this island, but the actual conquest was initiated only by the emperor Claudius, who invaded in 43 CE. Over the next years, there was a gradual conquest of the island.

Julius Agricola should be mentioned here, who managed to reach Scotland (Caledonia) and also stated that Britain is an island. In the years 122-126 CE, Emperor Hadrian decided to build a rampart of fortifications between the Solway Firth and the Tyne Estuary (Hadrian’s Wall).

During the reign of Antonin Pius, the border was further shifted and the construction of the so-called Antonin’s Wall (connecting the Firths of Forth and Firths of Clyde). Emperor Commodus resigned from these acquisitions.

The Romans left Britain only in 407 CE when Constantine decided to do this in the fight for the crown with Honorius.

The strategic city of the province was Londinum (present-day London).

Britain in the 5th century CE

The fate of Britain in the first half of the 5th century CE is probably one of the most mysterious cards in European history. Britain, the northernmost province of the Roman Empire, has always been treated somewhat neglectfully by its rulers. Romanization had the least impact here, Roman cities and military colonies were built the least. No wonder, then, that this misty, cold island was the first to be written off in the face of the impending catastrophe of the entire Western Empire.

In 396 CE a great invasion came upon Britain from almost all sides. The Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Iro-Scots and Picts flooded the island with a mighty wave. This time, however, for the last time, Rome took care of its farthest possession. The rescue expedition was led by the regent of the west himself, half Vandal, Stilichon. He defeated all the barbarians one by one, then thoroughly cleared the island of garrisons and rushed back to Italy to fight the Visigoths. His retreat in 402 left the Isle virtually defenceless. The disaster brought by the hard winter of 406 CE also affected Britain. The Alans, Suebi, Vandals and Burgundians crossed the frozen Rhine and thus cut Britain off from all help from the continent. In the face of another intensification of Saxon attacks, the Romano-British sent a letter begging for help to the emperor Honorius himself. They picked a bit of a bad time. The year was 410 CE and Alaric’s Visigoths were just taking everything of value out of Rome. It is not known exactly whether Honorius replied to the letter. In any case, the commanders and aristocracy of Roman Britain were left to their own devices.

The British-Roman aristocracy, the Celtic communities and the remnants of the legions of the northern army – this whole conglomerate was left without a supreme authority. Local commanders, latifundists and chieftains quickly turned into independent rulers. The “political map” of Britain at that time is unfortunately impossible to recreate. However, archeology provides us with some valuable information. For example, there are no signs that the fortresses along Hadrian’s Wall were suddenly evacuated or destroyed. Probably the defence of the northern border held all the time. Welsh tradition mentions the alleged last commander of the British legions, calling him the Celtic name of Coel Hen.

One of the few written sources, De Excidio Britanicae, written by the British priest Gildas (mid-sixth century), claims that the autocrats of Britain once again turned to Flavius Aetius for help. “The barbarians drive us into the sea, and the sea drives us back among the barbarians,” the chronicler quotes this semi-fictitious letter. Aetius, however, with the whole Gallic mess on his head and, in addition, the Huns preparing for the invasion, had absolutely no strength and resources to cross the Mare Germanicum.

In this situation, however, a man appeared who managed to concentrate power over Britain in his hands. The Welsh chronicler Nenniusmentions a war between two chieftains: Ambrosius Aurelius and Vitalinus. Nennius mentions the former’s ancestors “wearing purple”, surviving in Welsh lore as Emrys. That’s pretty much all we know about him. The second, Vitalinus, won the war and numerous references to him appear in various sources – Gidas, Nennius, and even the venerable Beda in his famous Historia Ecclesiastica Gentis Anglorum (Beda’s work is the primary source for the era, unfortunately, the author was a typical Anglo-Saxon nationalist).

Vitalinus is mentioned in the sources as Gwrtheyrn or Vawr-Tigherne – Vortigern, meaning “high chieftain” or “overlord”. He probably came from the western British colony of Glevum, and Welsh legends speak of him as the founder of the famous Powys dynasty. Gidas writes about him as the absolute ruler of all of Britain, but unfortunately, this source is not entirely objective – Gildas is, after all, a British-Roman who criticizes the Anglo-Saxons at every turn. Today, opinions about Vorigern are also divided. Celtophilic historians see in him what was introduced in Britain by the office of the high king (following the Irish Ard-Ri of Tara). Others see him as a hegemon or even just a distinguished Celto-Roman chief. It is even believed that he abandoned Christianity and practised polygamy.

Regardless of who Vortigern was and what his official or unofficial function was, it is certain that he brought Hengest to Britain. Hengest was a German of not entirely clear origin. He might have been Angle or Dane, though he might as well have had the blood of both tribes in his veins. The house he was supposed to represent was said to be called the Scyldings. The story of Hengest is one of the subplots of the famous epic poem Beowulf as well as other Anglo-Saxon sagas. Hengest was to engage in battle with the Frisian king Finn and, after numerous adventures and intrigues, kill him. These events, known as Freswael and later regarded by the Angles as the “myth of origins”, made him famous, but also hated by many northern pirates, such as the Angles, Saxons, Frisians, Jutes and Danes. Seeing that the earth was burning under his feet, Hengest gathered a small but experienced and well-equipped band of mercenaries from various tribes and decided to hire himself somewhere far from his homeland – as long as there were too many enemies. There is one more problem with Hengest and his brother Horsa – namely their names. Hengest means “steed” in Old Germanic, while Horsa means “horse”. They were probably not names, but typical pirate nicknames, or names related to their tribal or team mark. Besides, most historians dispute the existence of Horsa.

Tabula Peutingeriana is a map showing the military road connections of the Roman Empire. It was an ancient “tourist map”. The original map (only copies have survived) is dated to the 4th century CE. Covers Europe, part of Asia (India with the Ganges), Ceylon Island (Insula Trapobane), Indian Ocean, China and North Africa.

Vortigern, having dealt with internal disputes more or less, had to face the unflagging attacks of Germanic and Irish pirates for a moment. He probably decided to use the Roman method of pitting some barbarians against others. That’s why he called Hengest. Gildas, knowing the painful consequences of Vortigern’s action for the Britons, unscrupulously calls him a traitor blinded by stupidity. By contrast, Bede glorifies Hengest and explicitly states that “The Britons are worth nothing, but their land is perfect.” One conclusion can be drawn about the figure of Vortigern – he belongs to those unfortunate historical figures who have had no luck with historians at all. Based on the comparison of sources, it was not even possible to determine the date of Hengest’s arrival and taking possession of the island of Thanet (“bright”), granted by Vortigern. Bede believes it happened in 449 CE, and Nennius gives 428 for a change. However, the event itself certainly took place. Hengest and his brother Horsa did indeed arrive in “three ships” and began fighting the other barbarians. Their subordinate Cunneda, the chief of a small Votadin tribe, was to deal with the pirates and, according to another legend, give rise to the equally famous Welsh dynasty of Gwynned (today’s Snowdonia). As for the other peoples with whom Hengest fought, we have no certainty either. Gildas calls all those attacking Britain by the common term transmarini, and it must be remembered that the Picts also attacked from the sea, by boats avoiding the line of Hadrian’s Wall. An indication that they also fought the Picts is the name of a town in Scotland – Dumfries (“Fortress of the Frisians”). In any case, Hengest gradually grew stronger as Vortigern’s power waned. Increasing numbers of Germanic warriors, and eventually settlers, began to annoy the Britons. With the loss of supporters, Vortigern’s financial capabilities also decreased. There was no more money to pay the wages of the ever-increasing mercenaries. Hengest therefore decided to throw off the completely fictitious supremacy of his British principal. The war began around the 550s and did not end for hundreds of years. Gildas presents these events in truly apocalyptic colours, depicting Dantesque scenes of slaughter and massacres. Fortunately, archaeology allows us to verify this information. It proves unequivocally that Londinum, Virocontium, Noviomagus and several other major cities were not conquered at all and held out for a very long time. Besides, the Germans do not seem to be able to conquer entire areas at once. Probably their fortified settlements were for a long time just islands in the Celtic sea. The defence of the Romano-Celts was completely disorganized by Hengest’s vile betrayal. Invited by Vortigern to meet the elders of Britain, he ordered his men to hide knives in their boots and slaughter the defenceless Celtic chieftains. It is unknown how Vortigern survived. This is the last mention of this chief. His further fate remains completely unknown.

Bede calls the start of the war a “boot” or even an Anglo-Saxon “rebellion”. It is hard to imagine more hypocrisy and partiality in the approach to the issue. Hengest’s successes, such as the capture of Eboracum and Lindum, encouraged more and more Germans of all tribes to emigrate to the Isle. At the same time, representatives of the British-Roman elites began to flee from Britain. A group of villages on the Seine called “Bretteville” is one of the traces of this migration that has survived to this day.

However, it was not so easy for the Germans. The British counter-offensive, led probably by Vortigern’s son Vortimer, caused Hengest considerable trouble. Three fierce battles were fought in the prefectures of Londinum and Cantium. In one of them, over an unidentified Riobogael ford, Horsa was to die (hence the old English name of the place: Horseford). In another, Vortimer fell, and thus Hengest was able to defeat the Britons. He became the founder of a dynasty that ruled Cantium (now pagan Kent) through the 6th and 7th centuries.

Hengest appears in Bede’s chronicle for the last time in 473 CE. We do not know when he died. Kent was succeeded by his son, Oisc. During his lifetime, the capital of Cantium, Durovernum (“Fortress over the Swamp”), changed its name to Cantwaraburg (“Kent’s Fortress”). Ripuarium and Dubris became Richborough and Dover. Slowly, traces of the recent Roman rule began to disappear from Britain. Kent was the first Germanic outpost, soon followed by the Angles settling north of the mouth of the Thames and the Saxons on the banks of the Channel. Over the centuries that followed, the warfare between the Germans and the Celts was to go on almost continuously, until finally the Anglo-Saxon heptarchy kingdoms of Kent, East Anglia, Northumbria (i.e. Deira and Bernicia united), Mercia, Wessex, Sussex and Essex were to drive the Celts into the inhospitable, mountainous regions of the island. Some of the Britons went to sea and settled in Armorica, giving rise to Brittany, others formed the kingdom of Strathclyde in the north and numerous Welsh principalities in the west: Gwynned, Powys, Dyfed, Glywysing or Dumnonie in Cornwall Gildas, witness to the gradual displacement of the Britons further and further into the mountains, he poured out on parchment bitter regrets and anger at Vortigern. From today’s perspective, you have to look at Vortigern’s decision in a completely different way. It was undoubtedly difficult, and at first, there was no indication that Hengest would become so powerful and eventually defeat the hegemon of British-Roman Britain. Besides, attacked from all sides, abandoned Britain would probably succumb to the violence of the Germanic invaders quite quickly. Bringing in Hengest only systematized this process and perhaps also accelerated it. History still cannot decide how to classify the characters of Vortigern and Hengest. What is certain is that they are a perfect symbol of the great change in the history of Britain, which was the end of Roman rule and the beginning of the German conquest.