Chapters

Caesar’s invasion of Britain in 55-54 BCE was an ambitious military campaign which proved that for this commander nothing was impossible.

Background of events

During the conquest of Gaul Caesar’s legionaries were constantly in contact with volunteers from Britain. In Britain itself, there were significant religious centres of the Celts, whose priests probably incited the peoples of the continent to fight against the Romans. In addition, they supplied weapons for the tribes and probably food supplies, using a well-developed merchant fleet of sailing Venets from today’s Vendée (western France). Anyone who felt an enemy of Rome found a safe haven there. An island separated by a canal could feel relatively safe against a formidable opponent who was Julius Caesar.

As if these reasons were not enough, there were legends on the continent about fabulous pearls, gold and riches. Roman merchant companies, tied to politicians by family and financial ties, probably also added their three cents. They took over ports in Northern Gaul. In order for trade with Britain to increase, trading posts, ports, roads and military crews were needed on the island to guard all goods and commercial infrastructure. Not to mention the new legions of slaves that would be transported to the continent.

The attempt to subdue Britain was also indirectly influenced by the general decline in interest in Caesar in Rome. The short campaign in Germania went unnoticed, which had nothing to do with the fame of the quick conquest of Gaul. Caesar himself, in 55 BCE, was after the aforementioned battles in Germania. The 18 days spent there meant that the Sugambras left their belongings in the escape, and the legions confiscated their grain and burned it, which could be burned. On the other hand, the Suebi were preparing themselves in fear to defend their territories. Caesar, content with the fear that the Germans had, decided to do the same in Britain.

Analysis of the Celts’ resistance to Caesar

First expedition in 55 BCE

From Caesar’s diaries, we learn that the author realized how little time he had left for the campaign, as the summer was drawing to a close. However, he feared that the Britons would continue to support the resistance movement of the fellow Celtic tribes of Gaul. The only option was to undertake an expedition similar to the ‘punitive expedition’ he had already made in Germany. Preparations began and the legions began to concentrate in the land of the Morins, at Portus Itus (today Bulogne). Caesar decided to learn a bit about the area he was going to subjugate. As Suetonius writes in “Julius Caesar”:

In the conduct of his campaigns it is a question whether he was more cautious or more daring, for he never led his army where ambuscades were possible without carefully reconnoitring the country, and he did not cross to Britain without making personal inquiries about the harbours, the course, and the approach to the island. But on the other hand, when news came that his camp in Germany was beleaguered, he made his way to his men through the enemies’ pickets, disguised as a Gaul. 2 He crossed from Brundisium to Dyrrachium in winter time, running the blockade of the enemy’s fleets; and when the troops which he had ordered to follow him delayed to do so, and he had sent to fetch them many times in vain, at last in secret and alone he boarded a small boat at night with his head muffled up; and he did not reveal who he was, or suffer the helmsman to give way to the gale blowing in their teeth, until he was all but overwhelmed by the waves.

– Suetonius, Julius Caesar, 58

On the other hand, thanks to the merchants, the news of the impending attack reached the island. The terrified Britons immediately send envoys with loyal promises. Caesar sends with them Comius, the leader of the Atrebates, so that he persuades as many tribes as possible to surrender to the authority of Rome. Meanwhile, the fleet gathers at Portus Itus. Eighty transport ships and a dozen warships were to set off with two legions on decks VII and X. So Caesar had about 10,000 legionaries along with several hundred horsemen. The cavalry had 18 transporters at its disposal, but had problems setting out. It took several hours for the fleet to reach the shores of the island. However, the place where it was moored had a steep, high coast. Fearing an ambush and attacks by barbarians who would have the upper hand under these circumstances, Caesar ordered to sail farther east towards Rutupiae, the oppidum of the Cantia tribe (today’s Richborough in Kent). The British packs moved in the same direction.

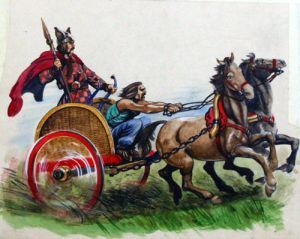

The Romans saw the ranks of the Celtic troops. Britons painted in the colors of war, who shouted loudly encouraged each other to fight. On the beach they maneuvered esseda (by this term, borrowed from the continental Gauls, the Romans called Celtic two-horse chariots, creases, which they knew at home for their parade and racing applications, but were used by British Celts in combat), which they made quite an impression on the Romans. Mounted and foot warriors were ready to meet. Unfortunately for Caesar, the transport ships, due to their size, cannot reach the shore. The first troops jumped from the ships straight into the deep water and engaged in hand-to-hand combat with the warriors. During each invasion, the landing party was put at a disadvantage. So also now “soldiers unfamiliar with the terrain, with their hands busy, laden with the great and heavy ballast of combat equipment, had to simultaneously jump off the ships, maintain balance among the waves and fight with the full freedom of body movements and perfect knowledge of the terrain, they threw missiles at our people and pressed horses tame with the sea on them “. The chief of the legions immediately sent for the warships that stood behind the transports. They swam from the flank to the exposed side of the Celtic troops and began firing from the machines on the decks. The firepower must have been considerable, since the defenders of the coast, surprised by this, withdrew, which enabled the Romans to bring all their forces into the fight. The famous scene follows in which the aqulifer (ensign) of the X Legion called for the taking of the legionary to land on the beach without fear. The cohorts discharged under “fire” and immediately clashed with the enemy. The fight was fierce and ruthless, and where the Britons had an advantage, reinforcements were immediately sent by boats and liburnias. In the end, a strong counterattack by the legions threw their enemies aside and forced them to flee. The chase was short-lived, because the tired legionaries could not run very far, and the ride had not depressed yet.

After the battle, there is a ceasefire. The defeated Britons promise to bring hostages and send Comius Atrebata, who was previously imprisoned with a 30-person escort. It was the only cavalry unit Caesar had since. It seems quite strange that Comius returns unscathed to Caesar. After all, the traitor and agent he was meant to be when he acted for the Romans should be at least tortured. Caesar only mentions the chains. It is known how the Celts could deal with prisoners. Perhaps the shackles were just an empty phrase, and the ride was separated from the Comius so that she would not be aware of the facts. The chief of the Atrebates could spread to the islanders a vision of Britain under the yoke of the Romans and urge them to fight against the total forces led by Caesar. After the battle, having their man, Commius, in the legion camp, they could be further informed about the leader’s steps. Atrebata could still pretend to be a friend of the Romans and wait for the opportune moment to reveal his true face. This only happened in Gaul.

In any case, both sides have several days’ time. On the fourth day, the legionaries can observe the fight of their fleet with the element. These 18 ridden transport ships attempted to reach their comrades, but dispersed, they succumb to a severe storm and return to the mainland. On the same night, a massive storm destroys 12 transports and seriously damages many others. Morale in the legions must have dropped seriously, the more so as no larger supplies were taken with them. The specter of wintering in Britain has become quite real. The waters of the canal could be very turbulent at the end of summer.

The Britons, informed of the troubles plaguing the legions by nature, decide to “start an uprising”. Apparently, Caesar thought too hastily that the Britons were already subjugated. The mere escape of the hostages from the camp suggests that there was someone who made it possible for them (read: Comius). Caesar vaguely calls it “sneaking out”, but it is strange that among several thousand legionaries there would be no guard in the camp. Meanwhile, the soldiers are making the appropriate repairs and clearing the surrounding fields of grain from the surrounding fields. These are the necessary preparations to leave the island and provide yourself with food. The Britons, informed of the separation of forces, (when one legion was in the camp, the other was sweeping the fields of grain) gathered their troops and prepared an ambush, into which the 7th Legion fell. Caesar rushes back with reinforcements and rejects the enemy. Fearing for the abandoned camp, he returns to it after some time.

Under these circumstances, our men being dismayed by the novelty of this mode of battle, Caesar most seasonably brought assistance; for upon his arrival the enemy paused, and our men recovered from their fear; upon which thinking the time unfavorable for provoking the enemy and coming to an action, he kept himself in his own quarter, and, a short time having intervened, drew back the legions into the camp. While these things are going on, and all our men engaged, the rest of the Britons, who were in the fields, departed. Storms then set in for several successive days, which both confined our men to the camp and hindered the enemy from attacking us. In the mean time the barbarians dispatched messengers to all parts, and reported to their people the small number of our soldiers, and how good an opportunity was given for obtaining spoil and for liberating themselves forever, if they should only drive the Romans from their camp. Having by these means speedily got together a large force of infantry and of cavalry they came up to the camp.

– Julius Caesar, Gallic War, IV.34

It comes to the third fight, but in the battle in the open field, the Britons have no chance against the legions. They retreat with Commius riding on their necks. On the same day, the deputies arrive asking for peace once again. Caesar orders twice as many hostages to be sent to the continent. Taking advantage of good weather, the legions leave the island the same night.

Lessons from the first expedition

Caesar achieved, above all, the main goal of his expedition, which is “to get to know the local people and get information about towns, marinas and access to land”. There was not enough time for more active hostilities and the number of troops turned out to be too small. Nevertheless, the battles on land showed that the legions were second to none in the field. The scouting nature of the first expedition is evidenced by the fact that the legions did not take large amounts of food with them. Caesar got acquainted with the fighting technique of the Britons, who constantly use war chariots, already forgotten on the continent. He also learned about tribal politics, which was not much different from that of the Gauls. She was shaky, after each defeat, they wanted peace to immediately take advantage of any weakening of the Romans.

The Roman naval operations failed all along the line. The lack of more cavalry prevented the Romans from destroying the tribes of Southeast Britain. The Roman fleet knew too little of the waters and currents surrounding the island to the south. It took a time that Caesar did not have. It can be called luck that he managed to return safely through the canal with both legions. Strangely, no other Roman officers are mentioned by name in his memoirs. Perhaps they have failed in difficult situations, or have not done anything special.

Second Expedition

Caesar prepares much better for the second trip. Already in winter, the legates stationed on the beds have orders to repair old ships and build new ones. Keeping in mind the nightmare of winds and currents in the canal, he orders the construction of new types of ships resembling today’s amphibians. They were wider to accommodate more animals and lower to better use the strength of the oars. Relevant parts were delivered all the way from Spain. About 600 and 28 warships of such transporters were built, and including the old and private-funded ships, the entire fleet consisted of more than 800 ships and warships. The forces that were grouped for the second expedition were five legions (including VII) and 2000 cavalry Gallic allies (about 25-30 thousand people). Legate Titus Labienus remained at the base camp (Portus Itius) with 3 legions and a similar number of horsemen. His job was to “defend the harbors and provide corn, and discover what was going on in Gaul, and take measures according to the occasion and according to the circumstance”1. It proves the great trust he had in this officer. Of the higher officers who were taken by former officers: legate Gaius Trebonius and Quintus Atrius (probably praefectus castrorum). Caesar was accompanied by the son of the leader of the Trinobantes tribe, Mandubracius, who would play an important role in the second expedition. Most of the chiefs of the Gallic tribes were also taken aboard so that they would not use Caesar’s absence to cause revolts. In the summer of 54 BCE, a huge fleet leaves Portus Itius for what is today Kent.

Landing

Most likely the landing operation was in the Richborough or Deal (Walter) area, but some are leaning towards Folkestone Beach (Corinne Mills, Richard Hayton). The cause of the problem of determining the landing site lies in the troubles of the huge fleet. At first a favorable wind pushed her from the southwest, but in the middle of the night it stopped and the sea current carried the ships more to the open sea, which threatened to destroy the entire fleet. In the morning the coasts of the Cantium (Kent) region were seen to the left. The soldiers sat on the oars and, using another current (from the north-east), reached the beach. Whether it was the same beach as last year is unknown. Caesar only writes in his memoirs that he “ordered” to row with all his might to reach that part of the island which he knew from the previous summer had the best access. Unfortunately, “ordered” does not mean that they got there. It does not mention anything about the old camp, which, after all, did not blur and could probably use it to quickly build a new one.

After landing from setting up the camp to guard it, Caesar leaves a force of one legion and 300 horsemen to protect the fleet at the anchorage. Alone, with the rest of his strength, he sets off at night at the enemy concentrating across the river (Stour for sure) in the hills (maybe Bigbury). The Britons perfectly fortified the wooded hills by building ramparts to strengthen their natural defences. Caesar calls such fortifications “castles”. Immediately, the 7th Legion begins to build the embankment under the testudo (“turtle”, that is, a makeshift shelter roof made of planks or shields). Then, without losses in the dead, it gains these fortifications. Caesar does not send the chase because he did not know the local area and was afraid of an ambush. Probably another indication that the landing might not have been at Deal but elsewhere. He probably uses the same hill to prepare the camp (then those areas were covered with dense forests so it was difficult to look for a better place).

The chase, grouped in three columns, starts the next morning and, after travelling a long way, encounters the rearguard of the British army. At the same time, the fearful news comes that the weather has once again played a trick on Caesar’s fleet. During the night, a gale damaged most of the ships, and 40 were lost forever. Unable to expose himself to stay on the island for the winter, he must turn back to take care of the injured fleet. The legions, meanwhile, retreat to the camp by the sea in order.

Selected legionaries are engaged in the repair, and all the ships have been hauled ashore. Here they were connected to form an extension of the camp, and their hulls played the role of an aggeru (dam). It took 10 days and nights for him to repair. In the meantime, the British Celtic tribes unite under the sceptre of the strongest of the tribes, chief of the Catuvellauns – Cassivellaunus. Hitherto they had fought fierce wars for domination among themselves, but Caesar’s expedition brought them to consolidation as such. After securing all matters and a letter contact with Labienus, Caesar sets off again the same path as before and with the same forces. Cassivellaunus is waiting for him with united forces. As before, the British warriors were equipped with war chariots and painted in battle paintings with dyeing wets (after drying and pulverizing the leaves of the woad, you can get a strong blue dye2), which was the custom of tribes in Britain. During the march, the riders of both sides clash. The Celts have to back off, but some of Caesar’s horsemen die in ambushes prepared for too hotheads. The way of fighting was completely unacceptable for the Roman leader. Forests, “guerrilla attacks”, quick retreats of small and dispersed combat groups did not allow the use of legionaries in formation, and the cavalry could not move too far in pursuit of the escaping enemy. There was a shortage of light infantry auxiliaries in the Roman units, unlike the Roman legionary infantry that could function effectively in wooded areas. Caesar describes how the Britons manage to attack the camp by surprise during construction, and even the first two cohorts dispatched must receive support. One of the stands dies during these fierce battles. The decisive battle takes place while gaining supplies. The Britons, untrained by the defeat of last year, decide to attack the “supposed” scattered and seemingly easy to defeat legionaries. However, three legions sent for food were prepared for a surprise. They were commanded by the legate Gaius Trebonius, who strikes back to protect the foragers. The driving attack was conducted with such ferocity that many opponents were eliminated. After their defeat, Cassivellaunus’s allies leave, leaving the Katuwellauns on their own.

The next battle takes place on the only ford on the Thames, which was the gateway to the land of the Katuwellauns. The decisive attack of the cavalry and the legions was not stopped even by sharpened piles driven to the bottom. Caesar mentions that fugitives come to him before the battle, which can only mean the complete collapse of the alliance of the British tribes organized against him. The Romans breaking through the Thames and losing allies causes a “domino effect”. The Trinity departed from Cassivellaunus, and the son of the leader killed by him – Mandubratius takes power as an ally of the Romans. The next five tribes depart. Caesar’s opponent, left to his own devices, has only 4,000 warriors, mostly on essedas (chariots). The Romans no longer have to worry about looking for grain that will provide them with supplies from the Trinovites. During the march to Verlamion3(the Romans called Verulamium) – the enemy capital may even use the “scorched earth” technique to a limited extent.

Cassivellaunus clings to the last resort to defeat Caesar or turn his troops back. With the help of seaside Cantia, he hits the Roman camp. The entire operation ends in a complete fiasco, and the tribal warlord is taken prisoner. At the same time, the last stronghold of the fighting Katuwellauns falls, and Caesar acquires the food stored there and great herds of cattle. Comius Atrebata again becomes an intermediary between the leaders of both sides. Oddly enough, Caesar writes that “through the Atrebata of Comius he sent envoys to Caesar with a declaration that he was surrendering”. So either Comius was one of his allies or remained as a secret agent – “eyes and ears” of Caesar on the island at the turn of the year 55/54 BCE Perhaps it was, as already mentioned, the “plug” of the Britons, and now he played the role of “double agent”. In any case, Caesar receives hostages as guarantees and sets the levies that the Britons were to pay to Rome. Appian of Alexandria mentions the great spoils that Caesar brought from Britain and Gaul, but from the descriptions of the chief himself, in which no “gold” is visible, we can conclude that it was probably about grain, cattle, maybe a supply of tin. One of the conditions of peace was also to cover the Trinity and prohibit attacking them altogether.

After returning to the sea, the army is crossed in two kicks. Since Labienus’s ships (60 of which he built) could not reach the shores of Britain, Caesar ordered the soldiers to pack tighter and happily swam to Gaul. The commander was in a hurry before the fall and foul weather, and there were revolts in Gaul again.