Chapters

Plebeian tribune (tribunus plebis) was an official in the Roman Republic. This post was created in 494 BCE to protect the interests of citizens, especially plebeians against the domination of patricians in the senate.

Establishment of the position of plebeian tribune – 494 BCE

The early Roman republic was headed by two consuls (executive power) and a senate (legislative power). Both institutions were available only to patricians. The most important and powerful Roman families concentrated in their hands all the power that they exchanged. Members of the commoners, in their opinion, had only economic and military value, which was regularly used. Moreover, the public land conquered as a result of hostilities was accumulated in the hands of gens (the most important Roman families), who were even further away from the commoners.

In 495 BCE, the plebs increasingly expressed their dissatisfaction with the debt he owed to the proprietary class, the patricians. A huge number of Roman farmers were mobilized for the war with the Latins, winning the battle of Lake Regillus. Plebs, being in the war, could not generate profits from their farms. As a result, he had to go into debt to support himself and pay his taxes. Failure to repay debts, in turn, allowed lenders to torture and exploit ex-soldiers; and even enslave them.

Roman historian, Titus Livius describes the story of an elderly man with scars on his skin (this proved his sacrifice on the battlefield), pale and sick skin, a long beard, and worn-out robes, he fell to the ground in the Forum Romanum – the city centre. There, he told other citizens his story. As it turned out, he was an officer in the Roman army in the war against the Sabines. During the conflict, his farm was burned and the cattle were slaughtered by the enemy army. Moreover, a tax was imposed on him which he was unable to pay. He had to take out a loan, but he had nothing to cover. As a result, he lost his grandfather and father’s farm. Lack of further funds to pay off his debt left him imprisoned, faced with death threats and scourged.

An agitated crowd gathered at the Forum Romanum and demanded a response and reforms from consuls Servilius and Appius Claudius Sabinus Regillensis and the Senate. Finally, the plebeians were heard by Servilius, who needed recruits to fight the Volscians who had invaded Rome’s Latin allies. In an effort to calm the crowd, the consul announced that no citizen would be imprisoned for refusing to report to military service. Moreover, if a legionary takes part in hostilities, his debt property will not be confiscated or sold; and his children and grandchildren will not be arrested. The debtors in prisons were released immediately. The actions of the consul calmed down the crowd and allowed him to gather the army with which he defeated the Wolsków.

After returning from hostilities, the plebs demanded specific decisions to improve the fate of the oppressed. The lack of threat from the outside made the patricians feel strong again and, through the second consul – Appius – took steps to enforce debts and imprison people who were unable to settle their obligations. The indignant crowd demanded a reaction from Servilius, who had promised them reforms before the war. Servilius – despite his sincere intentions – was unable to win the support of the aristocracy. He was thus hated by both camps: the plebeians considered him a traitor; patricians too weak.

Another threat was the combined invasion of the Roman lands by Volsci, Sabines and Aequi in 494 BCE. During this hard time, Manius Valerius Maximus was appointed dictator, who led the legions to victory. After returning to the capital, the dictator decided to ask the Senate to settle the issue of debts that plagued his soldiers. However, the lack of clear decisions and the tardiness of the senators meant that Valerius resigned from his position. However, his involvement was appreciated by the plebs.

Another threat from the Aequas forced the senate to announce the recruitment again. Plebeians, who were already completely discouraged from the patriciate and their empty promises, did not appear for conscription. What’s more, at the call of a man named Lucius Sicinius Vellutus, it was decided to leave Rome en masse. Most of the citizens of the “Eternal City” went to the nearby mountain Mons Sacer (“Sacred Mountain”) across the Anio River (the so-called plebeian secession to the Aequi Mountain – secesio ad montem Sacrum). A fort was built there, and around it, ditches and embankments. lex sacrata was voted, which entailed exsecratio – Jupiter’s anger in the event of breaking the law. The office of tribuni plebis was established, with a range of powers and the rank of the official.

The Senate, realizing that Rome would not defend itself only with the help of patricians, decided to send an emissary who would conclude an agreement with the separatists. Agrippa’s consul Menenius Lanatus persuaded the plebeians to return by comparing Rome to the human body. He suggestively proved that both plebeians and patricians must work together to keep the Republic alive. The plebeians were impressed by this comparison, which suggested that they are as important as the ruling class.

Plebeian tribune office

Finally, an agreement was reached, which assumed the official creation of the said office – a plebeian tribune (originally there were two or five officials), which was to uphold the rights of the plebeians and was elected only from among the commoners. The tribune protected the plebeians from the authority of the consuls; what is more, he was guaranteed safety – a violation of the tribune’s inviolability was punishable by death (sacrosancti).

Plebeian tribunes were appointed by plebeian assemblies (concilia plebis), in which only plebeians cast their votes. During the assembly, the tribunes sat on special benches at the Forum Romanum.

In 457 BCE the number of stands was increased to ten, and this number was maintained until the end of the republic’s existence in 27 BCE. Such a drastic multiplication of the office resulted from the actions of the senate, which thus wanted to limit the influence of plebeians on state policy.

The term of office of the tribune was one year. Only a plebeian could become a tribune of the people. In turn, if a patrician wanted to take this position, he had to first move to the plebeian state. A famous example is Publius Clodius Pulcher.

The re-election of people’s tribunes was forbidden and was maintained in this form throughout the existence of the office. However, in the beginning of the Republic (the time of rivalry between plebeians and patricians) and later (e.g. the tribunate of Gaius Gracchus), the law was omitted and the same person occupied the office. It was the election of Gaius Gracchus to the post of tribunus plebis in 122 BCE. it has given a kind of a gate for this type of practice.

Powers of plebeian tribunes

Plebeian tribunes were endowed with great powers, which grew over time, especially in the later period of the republic after intense battles between the state plebeians and patricians. Ultimately, tremendous power was concentrated in the hands of the tribunes. In order for them to be able to exercise it freely, a special resolution of the people (lex sacrata) guaranteed them holy inviolability (sacrosanctitas). Violation of this inviolability was punished with the loss of rights and even death. However, in order to limit their powers a bit, the Senate decided to reduce the sphere of the internal politics of the tribunes only to Rome. In addition, the tribune could have vetoed the decisions of the other tribune. Importantly, no other government official could object to the tribunal’s decision – apart from an emergency and an appointed dictator.

The tribunes could interfere in the activities of the entire magistracy (a group of offices), except for the dictator and censor. Moreover, they had the right to call a plebeian assembly and pass resolutions there, which, however, only concerned plebeians (the so-called plebiscita). The position of the tribune was so strong that many politicians tried to appoint their allies to this office so that they could effectively influence the lower spheres of Rome.

The tribunes also exercised the judiciary in political matters in the city. Over time, they obtained the right to apply the objection (intercessioor ius intercessionis) at the assembly (concilium plebis) against the senate’s motions, if they considered them harmful to the plebeians. It was the tribunal’s veto that changed the senate’s resolution from the binding (senatus consulltum) to the opinion-giving resolution (senatus auctoritas). From the 3rd century BCE, the tribunes were given the power to convene a senate to present a resolution.

The tribune also had the power to defend citizens against the Roman magistrate. As late as 300 BCE, the lex Valeria de provocatione law was adopted, which did not allow the consul to condemn a Roman citizen to death without first appealing to the people’s court (provocatio ad populum). Later this law was strengthened and the citizen could appeal against the decision of the official to one of the plebeian tribunes (the so-called appello tribunos! – “I call upon the tribunes” or provoco ad populum! – “I appeal to the people”). The summoned tribune assessed the legitimacy of the official’s decision and de facto granted extraordinary rights to the inhabitants of Rome. When perceived a violation of the law, the tribunal applied ius intercessionis and reversed the official’s decision.

Naturally, the plebeian tribunes had the right to listen to the deliberations of the senate and even to speak. It is worth emphasizing that the powers of the tribunes were valid only in the case of his physical presence.

Famous People’s Tribunes

The following examples show how much power the tribunes of the people had in their hands, how in practice, at the end of the republic, disputes were settled and social agreements were complied with.

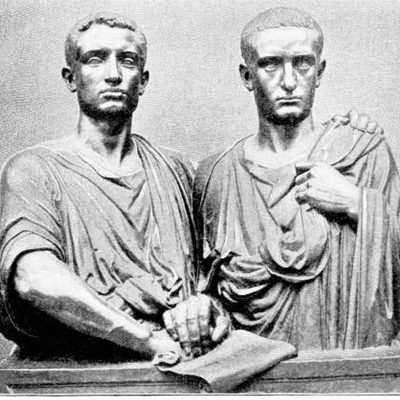

Tiberius and Gaius Sempronius Gracchus

In the second half of the second century BCE, a crisis was growing in Roman society, caused by the rapid changes after the conquests. The amazing territorial development of the Roman state allowed high social groups to increase their wealth at the expense of the poorer strata.

The rich bought large estates in which slaves worked, massively imported from various parts of the country. Small landowners, who were the backbone of the army, spent a long time in the war. This fact was used by the rich who seized their property. The loss of property led to the fall of the middle-class Romans below the property census. This, in turn, prevented them from joining the army. This situation on a mass scale could have tragic consequences for the entire country1.

In 133 BCE, Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus appointed the tribune of the people, who proposed agrarian reform to help the poorest people. The reform was largely based on the foundations of the law of 367 BCE, which was part of the so-called Leges Liciniae Sextiae. On this basis, it was decided to set the maximum area of land for one plot per 500 jugers (1 juger=2520.6 m2). Each farm could get an additional plot of 250 Jugers for the two eldest sons of the user ager publicus. It is easy to calculate that the maximum area of land distributed under the law in question could be 1000 Jugers. The area exceeding the boundaries indicated in the act was to be returned and then divided into 30 Juger plots, which were planned to be allocated to poor, landless peasants.

A special commission worked on the distribution of land, and Tiberius himself had a group of 3,000 helpers, which caused anxiety among the upper classes. Tiberius was accused of striving for a monarchy when, after the end of his term in office, he wanted to apply for a second tribunal for 132 BCE – which was contrary to previous social agreements.

On the day of the election, a group of clients and slaves attacked the former tribune, called the “enemy of the republic”, of the senators who were reluctant to Tiberius and the then high priest (pontifex maximus), Scipio Nasica. Together with the aforementioned group of allies, Tiberius took the Capitol, preparing for a possible armed struggle. During the fighting, Tiberius and about 300 supporters of the reform were killed. Some of the survivors were knocked off the Tarpeian Rock, and the rest were scattered throughout the city.

Tiberius was followed by his younger whip, Gaius, who did not abandon his plans for reform. In 126 BCE he received a tribunal. He confirmed the agrarian law of Tiberius and repealed all Senate legislation that blocked the reform. His reforms were also aimed at equality of rights for all inhabitants of Italy, which was to be expressed by granting Roman citizenship. A brave matter met with great resistance both from the optimists and the popular.

Gaius held his office for 123-122 BCE An attempt to extend his office to 121 BCE ended as tragically as it did for his brother. Ultimately, the dispute between the supporters of both parties took place on the Aventine Hill, occupied by Gaius and his people. On that day, 3,000 of his followers died along with Gaius.

Publius Clodius Pulcher

In December 59 BCE, Publius Clodius Pulcher became a plebeian tribune, previously leaving the patrician state. He managed to beat the other candidates because of the populist promises he made and later put them into effect. The most important of these was to provide free grain for the city’s citizens. After taking office, Clodius introduced a law according to which anyone who killed a Roman citizen without trial is to be expelled. It was aimed at Cicero. It was he who in 63 BCE, as a consul, ordered the loss of some of the allies of Catiline (including Lentulus Sura) who planned to overthrow the current government. Clodius, to emphasize his victory, demolished the house of Cicero and in its place erected a temple dedicated to Libertas.

After getting rid of Cicero, the position of Clodius increased significantly. He formed armed groups of his followers to support him. However, at the same time, his relationship with Pompey, Caesar and Crassus. In this situation, people loyal to Pompey – Titus Milo and Publius Sestius – organized their own “gangs” that could resist Clodius. The struggles of Milo and Clodius in the streets of Rome continued until the death of the latter and the exile of the first in 52 BCE. The events of these years perfectly illustrate how weak the Republic was and why it was replaced by a new order soon after.

Decline of the importance of office

With the victory of Octavian Augustus in the civil war, the office of the people’s tribune lost its importance, and some of his powers were taken over by princeps. Officially, elections were still held in the empire, and you could remain a people’s tribune until the 5th century CE. Until the third century CE, a plebeian, in order to be able to sit in the senate, had to obtain the office of people’s tribune; the role of the tribune, however, was only marginal and titular.