Chapters

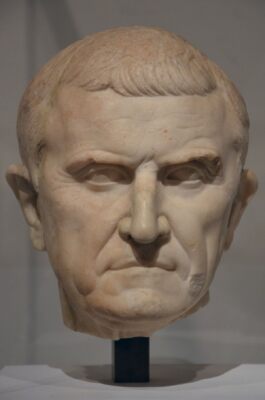

Marcus Licinius Crassus was born in 114 BCE. He was a Roman politician and commander, a member of the First Triumvirate. Known for his wealth, he died in the battle of Carrhae. Crassus, despite his great political importance in the first century BCE, remained in the shadow of Pompey and Caesar.

Family and background

Crassus came from a rich family with senatorial traditions. He was the second of three sons of an influential senator Publius Licinius Crassus – consul vir triumphalis in 97 BCE and censor in 89 BCE. His ancestor was supposed to be, among others, Publius Licinius Crassus Dives, which is currently questioned. The eldest brother, Publius (born c. 116 BCE), died shortly before the Social War (91-88 BCE). Marcus, after his brother’s death, married his wife. Father and younger brother Gaius committed suicide later during winter in 87/6 BCE in order to avoid being captured by the forces of Gaius Marius.

Gens Licinia possessed three branches in the second and first century BCE, and it is difficult to identify Crassus’ ancestors. His homonymous great-grandfather Marcus Licinius Crassus, praetor in 126 BCE, received a funny Greek pseudonym Agelastus (Gloomy) from the contemporary living Lucilius – the creator of satire as a literary form. Great grandfather was the son of Publius Licinius Crassus, consul in 171 BCE. Another line of Licinii gave birth to a certain Lucius Licinius Crassus, a consul in 95 BCE, who was the most famous speaker before Cicero. Marcus Crassus was also a talented orator and a very energetic advocate.

Youth

After the purges led by the supporters of Gaius Marius and his unexpected death, consul Lucius Cornelius Cinna (better known as Julius Caesar’s father-in-law) ordered proscriptions to punish the living senators and equites who supported Lucius Cornelius Sulla in his march to Rome in 88 BCE and overthrowing the Roman order.

His family lost its fortune as a result of Cinna’s proscriptions, as he wanted to punish the followers of Sulla, including Crassus. This situation forced Crassus to flee to Spain. After Cinna’s death in 84 BCE Crassus went to Africa, where Sulla’s followers were gathering. When Sulla returned from a successful Parthian expedition and took up the invasion of Italy, Crassus joined forces of Sulla and Quintus Caecilus Metellus Pius. He was a commander during the battle of the Colline Gate on 1 November 82 BCE. This battle was a decisive one and ended the Populares’ rule in Italy. Sulla was declared a lifetime dictator, ruling until his death in 78 BCE.

Marcus Crassus, thanks to the victory over Sulla’s supporters, could take up the property of his family, plundered during the rule of Cinna. According to Plutarch, during the dictatorship of Sulla, he benefited from proscriptions against the Populares, rebuilding family assets. He made a lot of money on construction, silver mining and – illegal in the light of Lex Claudia de senatoribus – loans on interest. He organized a “fire brigade” for Rome. At the time when the fire broke out Crassus with his “firemen” (a branch of 500 slaves – architects and builders) appeared on the spot and first bought the building with the land for a very low price, and then his people proceeded to extinguish the fire. This way he became the owner of a large part of Roman estates. Crassus also aggrandized his wealth in a more traditional way, engaging in slave trade. Plutarch estimated Crassus’ wealth at 200 million sesterces. According to this historian, his wealth grew from less than 300 to 7100 talents, or about 25 billion zlotys. Such estimates are given by Plutarch just before Crassus’ expedition to the Party in the 1st century BCE.

Political career

After rebuilding his fortune, Crassus decided to focus on politics. As a follower of Sulla, the richest citizen and descendant of consuls and praetors he had a clear cursus honorum. However, his person was regularly effaced by a political competitor – ambitious Pompey, who forced dictator Sulla to allow him to triumph in Rome for his victory over the Roman rebels in Africa. It was the first time that a Roman general would triumph after defeating native Romans. Crassus, moreover, was jealous of Pompey as he did not become a praetor before having triumph. The rivalry and jealousy were to determine the future career of Crassus.

Crassus traditionally and in accordance with the legal requirements successively filled the offices required in the so-called “path of glory”. Unexpectedly, Rome was shaken by two events: the Third War with Mithridates VI(73-63 BCE), the King of Pontus, and the slave uprising led by Spartacus (73-71 BCE). Facing such threats, the Senate sent Lucius Licinnius Lucullus to the east. Lucullus was to defeat the ruler of Pontus and stop his expansive intentions. At that time, Pompey fought in Spain against Sertorius, the last representative of the Marian army.

According to Appian in 73 or 72 BCE Crassus held the praetor office, which empowered him to command the Roman army. At first, the Senate did not treat the slave rebellion as a threat to Rome. Crassus, aware of the strength of the rebels, after a series of defeats, offered equipment, training and leading troops at his own expense.Eventually, the Senate agreed to that proposal. Initially, Crassus had problems predicting the movements of Spartacus troops and raising the morale of the legions. When one day the Roman army escaped from the battlefield, leaving equipment, Crassus decided to restore and apply the Roman military penalty – decimation. Plutarch mentions that the soldiers who watched the whole event witnessed terrible things. Crassus idea was so effective that the Roman legionaries became extremely punitive and were more afraid of his anger than the enemy.

Crassus along with, then young and inexperienced, Julius Caesar drove Spartacus to the headland of Italy, where he began to build fortifications in order to cut off his return journey. Spartacus decided to get to Sicily and join the slaves there. This plan, however, was not implemented, because the corsairs who were supposed provide ships, did not live up to their promises. Spartacus, however, managed to get out of the trap. Soon, in the army of rebels, another split occurred. Two Gallic chiefs stepped out of the army, taking their followers with them, which definitely weakened Spartacus. The troops that left Spartacus’ army were soon destroyed. The next battle was the one of the Salaries River in Lucania. Crassus defeated the gladiators, regaining the insignia of the defeated legions. Spartacus evacuated to the southern tip of Italy, where he won one battle.

Meanwhile, Pompey came from Spain in order to to help Crassus, and also the army of the governor of Macedonia, Lucullus, arrived in Brundisium. In 71 BCE in Apulia, close to Brundisium, there was a decisive battle of the Silarius River between the armies of Spartacus and Crassus. This is extraordinary event was described by a Greek historian, Appian of Alexandria:

When Spartacus learned that Lucullus had just arrived in Brundusium from his victory over Mithridates he despaired of everything and brought his forces, which were even then very numerous, to close quarters with Crassus. The battle was long and bloody, as might have been expected with so many thousands of desperate men. Spartacus was wounded in the thigh with a spear and sank upon his knee, holding his shield in front of him and contending in this way against his assailants until he and the great mass of those with him were surrounded and slain. The Roman loss was about 1000. The body of Spartacus was not found. A large number of his men fled from the battle-field to the mountains and Crassus followed them thither. They divided themselves in four parts, and continued to fight until they all perished except 6000, who were captured and crucified along the whole road from Capua to Rome.

– Appian of Alexandria, Roman history, XIII 120

In 71 BCE Crassus, the propraetor, suppressed Spartacus; uprising. He ordered to crucify six thousand captured slaves along via Appia. After this victory, he was granted the right to ovation (crossing Rome on foot and offering sheep as a sacrifice). The ovation was seen as a less significant glory to the winner than triumph. However, as historians point out, it was thought that suppressing the slave rebellion (despite its real threat to Rome) was not worthy of a triumph. In addition, Pompey and Crassus were elected consuls in 70 BCE. This year, Crassus showed off his wealth by organizing a public festival of Hercules. To this end, he organized a mass feast for the people and provided grain for each family for three months.

While filling the office, Crassus and Pompey fought the Optimates by allying with the Populares in the interest of whom they introduced the bill (Lex Pompeia Licinia de tribunica potestate) restoring all the powers to the tribunes of the people.

When his term of office came to an end, Crassus – in contrast to his political opponent, Pompey – remained in Rome and created a dedicated faction based on family connections and – above all – his financial power. Not much is known about his activity in the years 69-66 BCE. Controversy arouses from his alleged involvement in the Pisonian conspiracy (also known as the Catilinarian conspiracy) at the turn of 66 and 65 BCE. Then began his collaboration with another leader of the Populares, Gaius Julius Caesar, whom he supported financially. In 65 BCE Crassus was appointed censor (together with Quintus Lutacius Catullus). This office brought him a lot of splendor, although not real political benefits, because most of his plans were torpedoed by a colleague at the office. This concerned both attempts to give citizenship to the inhabitants of Gallia Transpadana, as well as a planned trip to Egypt, aimed at taking over the country in virtue of Ptolemy Alexander’s will. Both politicians renounced censorship before the end of the term.

As probably the richest man in the world at the time, he joined, together with Pompey and Caesar, in the First Triumvirate in the year 60 BCE. Caesar himself had a great influence on this agreement, he was able to reconcile the ambitions and mutual hostility of Crassus and Pompey. The triumvirate was to be valid until the death of Crassus.

As it turned out, however, the agreement of politicians was not certain. Relations between Pompey and Crassus continued to be hostile. Pompey, at the beginning of the year 56 BCE, claimed during the the Senate’s meeting, that he knew about his planned assassination, which was supposed to be finance by Crassus. Such open hostility between the two triumvirs caused that the Optimates began to attack Caesar, whom they hated the most. There was a threat, if the consulate was granted to Lucius Domitius Ahenobarbus in 55 BCE, that Caesar would lose the governorship of Gaul. It could not be allowed. To this end, Caesar met Crassus in Ravenna, where they both agreed that an agreement should be made with Pompey and thus they renew the triumvirate.

Both triumvirs, in 56 BCE, went to the city of Luka (on the border of the province of the Cisalpine Gaul and Etruria), where also in April, after some hesitation, Pompey joined them. The triumvirs decided to maintain their binding arrangement. They determined that Crassus and Pompey would apply for the consulate the following year, and then receive governorship in the respective provinces. With obtaining the office in the year 55 BCE, a new bill, lex Trebonia at the request of the tribune Trebonius, was introduced on which basis each consul was granted 5-year governorship over the provinces – Crassus received Syria and an extraordinary power to begin war against the Parthians, and Pompey got Hispania Citerior and Ulterior.

War with the Parthians and death

Crassus, having received the rich province of Syria under his administration, dreamed of defeating the neighboring Parthian Empire. The entire eastern campaign resulted from Crassus’ need for the glory, who wanted to match the other triumvirs, Julius Caesar and Pompey the Great, with his military achievements. The neighborhood of the rich Parthian Empire, which controlled part of the Silk Road and trade between the Mediterranean world and India, stimulated Crassus’ imagination, who wanted easy Roman conquests in the East. He planned to cross the Euphrates at the head of the legions and conquer the exotic Parthian Empire. The King of Armenia, Artavasdes II, offered to support Crassus’ expedition with 40 000 armed men (10 000 cataphracts and 30 000 infantry), provided that Crassus invade the Parthian Empire from Armenia’s side. This way, the king would have an army in place, and Crassus would have a safe march. Crassus finally resigned from the offer and chose a faster route, crossing the Euphrates at the head of about 40 000 legionaries.

Battle of Carrhae

A detailed description of the defeat of the legions in the clash with the Parthian cavalry.

Finally in the year 53 BCE Crassus’ army was destroyed by the Parthians in the battle of Carrhae during which his son, Publius Crassus, was killed. Marcus Licinius Crassus tried to get to Armenia, but he was killed during peace negotiations with the messengers of Surenas, a Parthian commander. Roman messages say that the Parthians poured molted gold into Crassus’ throat. They mocked the rich man, asking how it tasted. Roman chief was then beheaded and his head sent to the Parthian King, Orodes II, to Seleucia over the Tigris. Greek actors at the Orodes’ court used her as a prop on the stage during the performance of Euripides’ Bacchae.

Crassus’ importance

Romans in China

Were the Romans in China?

With the death of Crassus, I triumvirate – an agreement between the three most important people in the state deciding about the political situation in Rome – broke. With time, this fact led to the aggravation of tension between Caesar and Pompey and the outbreak of civil war. It is worth mentioning that around 20 000 legionaries were killed in the battle of Carrhae, and 10 000 were captured. The latter, according to Pliny the Elder, were settled in Margiana (a land in central Asia, located near the Chinese state) in the eastern part of the Parthian Empire, to guard the borders against nomad invasion. To this day, it is not really known what happened to the Roman legionaries who had been taken prisoners. There are speculations that some of them escaped, went east and joined the wild Huns, and from there even got to China.

Crassus was undoubtedly a decisive person in Rome in the end of the Republic. His wealth allowed him to expand his network of allies and clients, whom he gained mainly through granting loans or defending them in court. His dreams of matching the fame and military achievements of Caesar and Pompey led him to the Parthian Empire. There he died in the summer of 53 BCE, covered with the sand of Mesopotamia.

The best summary of the person of Crassus can be found at Plutarch:

(…) the many virtues of Crassus were darkened by the one vice of avarice, and indeed he seemed to have no other but that; for it being the most predominant, obscured others to which he was inclined.