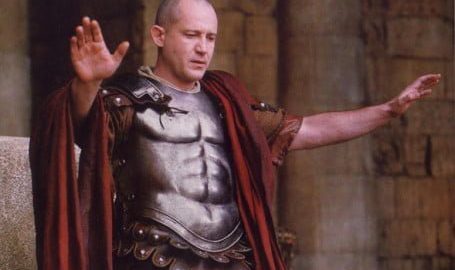

The governors of the Roman provinces had such power that they could use the subordinated territory in an absolute way. This situation took place practically throughout the entire period of the existence of the Roman state, but we have extensive knowledge especially about the first century BCE. Rarely then, there was a fair and reasonable administrator, the example of Cicero.

Cicero described the relations in the provinces as follows:

All provinces are crying, all independent peoples are complaining, all kingdoms are complaining about our greed and rape; there is no place on earth so far away that our officials’ arbitrariness and injustice would not reach. Rome does not have to be afraid of foreign peoples, but of complaints, tears and regrets, not weapons and war1.

As a result of rip-offs in the provinces, the aristocracy’s wealth increased significantly. People living in the provinces were often obliged by the governor to pay high taxes to the state and fill the private treasury.

The self-will of administrators, however, was not without response from the more moral elites. Rip-off trials (de repetundis) have been formed in Republican Rome. Many Roman politicians were brought before the tribunal: in 69 BCE the promoter of Gallia Narbonensis Marcus Fonteius, in 66 the historian and speaker Gaius Licinius Macer and Dundanius or the tribune of Manilius. In 65 BCE before the tribunal, Catiline is brought for embezzlement and rip-offs in Africa; in 63 Gaius Calpurnius Piso was accused of abuse of power in Gallia Narbonensis; and in 59, Lucius Valerius Flaccus for his activities in Asia.

However, they were not always guilty in court. It happened that the former governor avoided the trial due to an influential friend – e.g., Salustius with the help of Caesar.