Chapters

Roman triumph (triumphus) dates back to royal times. It was due to the victorious ruler, and initially, it was associated with the ritual of cleansing the soldiers – so it was primarily a religious ceremony. Over time, however, it gradually lost its religious character, becoming a more and more spectacular show to the satisfaction of the commoners. Of course, the propaganda function was also important, both state-owned and private, i.e. ancestral. After all, every Roman leader dreamed of full triumph and gaining glory for himself and his family.

As time passed, the potential winner began to be subject to certain conditions that had to be met first to be able to claim the right to triumph.

Conditions for granting the right to triumph |

|

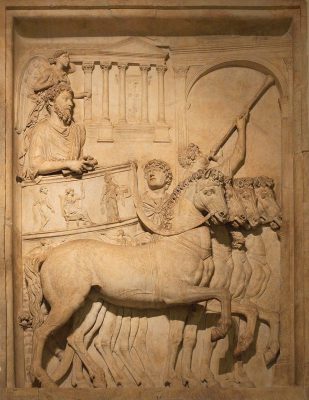

Two types of triumphs were distinguished: triumphus curulis (the so-called great triumph), during which the winner was riding a quadriga-type chariot (currus triumphalis) and the conditions set for the emperor were presented above. The second type of triumph is ovatio (ovation) when the chief rode a horse or walked. However, their varieties were also distinguished.

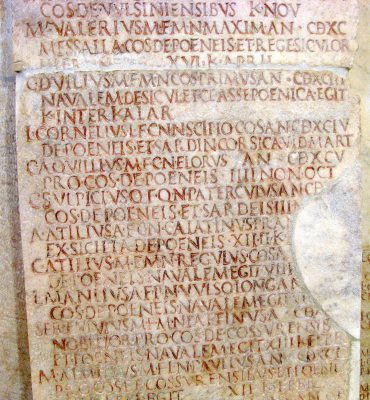

The proper triumph – “great” (triumphus curulis) took place in Rome with the consent of the Senate and at the expense of the state. Failing to obtain such permission, the chief, at his own expense, celebrated triumph on the Albanian Mountain (triumphus in Monte Albano). This kind of celebration dates back to 231 BCE. Its course and significance did not differ in any way from the city triumph, but it was certainly less grand and honourable. Along with the victories of the Roman fleet at sea, there was also triumphus navalis, which was connected with the setting in the city of columna rostrata (a column decorated with beaks protruding from the shaft) defeated ships). The last variation of the triumph was the aforementioned ovatio (ovation “little triumph”, minor triumphus), the beginning of which we date to the period of the Republic.

A proper triumph

The triumph had two essential features: on the one hand, it was a tribute to the gods, and on the other, it was an honour to the leader. The sacred element of this institution was supplicationes. They were arranged mainly on the occasion of victory and in honour of the victor, although they belonged to the gods. Over time, the religious aspect turned into a secular one. During the empire, supplicationes honoured a victorious leader. With the end of the Republic and the beginning of the Empire, the religious aspect gave way to the political aspect.

Another sacred element was the conviction that triumph was a duty to the gods, linked by votum (a promise to the deity) with the auspices of a leader. Equipped with auspices, the commander also received the approval of the gods for the war campaign. Asking for this consent, before going to the battlefield, he made sacrifices in the temple, through which he made requests to the gods, at the same time committing himself to fulfil them. Hence, the spoils of war offered to the gods during the triumph were the fulfilment of the conditions set for victory between the chief and the god. Triumph was a sacred duty, and any refusal to triumph was tantamount to offending God and the winner. It is not known how the above duty to a god was fulfilled in the event of a refusal of this honour. One solution could then be the aforementioned triumph on the Albanian Mountain, held without the consent of the Senate at the request and expense of the commander himself.

There was also a magical sacred aspect in the triumphal ceremony. It was included in the act of passing a triumphal march through the triumphal gate, which had a purifying meaning. The army then freed itself from all the evil that war brings with it. The laurel worn during the festival by the triumphant or by soldiers had the same meaning. Apart from the cathartic aspect, we also observe the existence of an apotropaic aspect. Defence against demons and evil spirits was provided by amulets placed on the triumphal carriage and the body of the triumphant. The purple robes, and the staining of the face would pass, must also have an apotropaic meaning. The slave’s word behind the triumphant was to ward off evil spirits.

In summary, the triumph was reserved only for those leaders who owned the empire and waged a suis auspiciis war (according to the auspices). In addition, only Roman citizens by birth could have this honour. From the times of Octavian Augustus (27 BCE – 14 CE), only the emperor and his family members were entitled to triumph, while other chiefs received ornamenta triumphalia. Auspices covered only the duration of the war and ended with the crossing of the city border (pomerium). If the winner entered Rome before the triumph, he immediately lost the right to it because of the auspices thus lost. For this reason, reports on the course of the war were submitted by the commander to the Senate outside the city walls. The Senate also passed a resolution on the triumph outside the city walls. When granting consent to celebrate the holiday, the Senate took into account the conditions that had to be met. Triumph, therefore, was only due to a successful war, not a single battle. It was impossible to achieve triumph for victory over pirates or slaves. Moreover, the declaration of war should have been carried out by the law, and the leader who was to conduct it had to have the consent and authorization of the Senate and the Roman people.

After the triumph, the victorious commander ordered the minting of coins commemorating this event. For example, the coin Pompey the Great– a golden aureus – from one of the triumphs showed on the obverse a head personifying the conquered Africa, the title of Pompey Magnus, meaning “the Great” and the wand and the pitcher as symbols of his divination. On the reverse, in turn, was Victoria on a chariot.

The commander was allowed to wear the robes and attributes of the winner for one day only. Later, these items were placed in a place of honour in the atrium so that every visitor to the household had a chance to admire the power of the family. Any attempts to wear these items or clothes in public have been criticized and, as in the case of Julius Caesar, have led to suspicions of an attempt to restore the monarchy and his murder. In the event of the chief’s death, in the funeral procession, the actors used attributes related to the triumph and put on triumphal robes or a laurel wreath to emphasize his achievements.

The victory of the leader, his triumph and the huge spoils of war he had won allowed ambitious politicians to participate in public, e.g. by commissioning and paying for the construction of temples or theatres. For example, Pompey in 55 BCE commissioned the construction of the first stone theatre in Rome, which became a gift to the Roman people. Julius Caesar, in turn, in 46 BCE, after his triumph, founded the temple of Venus as his and the patron saint of his family.

The early triumphs of the royal and early republican era were certainly modest. They were to welcome the victorious leader and the army, admire the spoils of war, and finally celebrate divine intercession by making offerings. However, with the growth of the Roman state, the number of victories and the multitude of spoils and successes, the way of celebration changed.

The course of proper triumph

The victorious commander stood with the army in front of the holy borders of the city borders (pomerium) and asked Senate members for their arrival1, to present a detailed report to the Senate, including a list of victories, spoils of war, conquered areas. Then the Senate considered the request, but there were cases where the Senate itself issued a resolution awarding this honour to the winner. In the event of approval, the Senate referred the matter to the plebeian assembly, which, if it also accepted the request, the triumph could be organized at the expense of the state.

Having received permission, the triumphant could enter the city without fear of losing the title of emperor. The route was clearly defined and led from the Field of Mars, via Forum Boarium, Circus Maximus (a few laps were made for 150,000 spectators), near the Palatine Hill and via Sacra at Forum Romanumand further to the Capitol2. Perhaps some prisoners sentenced to execution were left in the vicinity of Tullianum (prison). The whole procession (pump) took about 4 km and was slow; the triumph began with the appearance of the first rays of the sun. All economic activity on that day was dying down, and the inhabitants gathered along the established route of triumph, wanting to admire the treasures and the unknown, conquered world.

The winner stood on a quadriga (circular, richly decorated with gilding and ivory inlays, closed on all sides and always harnessed by four white horses), wearing a purple, gold-trimmed toga (toga picta) He held a laurel twig in his left hand and an ivory sceptre topped with an eagle in his right hand. His face was painted red like the statue of Jupiter3. Behind him on the chariot was often a state slave, holding a golden wreath over his head, reminding him now and then that he was only a mortal (“Remember you are mortal”). In this way, they wanted to limit the aspirations of ambitious leaders who, taking part in the triumph, were to personify, above all, the entire victorious Roman nation. However, apart from the moral aspect, the triumph was an opportunity to show off to the masses of Romans and a great tool for creating your political image.

The procession was opened by models and images of conquered lands and cities or crossed mountains and rivers, which were transported on huge carts. In the case of conquering truly exotic places, wild animals (e.g. elephants, giraffes) that were unknown to the Romans were also led. There were also paintings and visualizations of key, victorious battles of Roman legions on the wagons. For example, Julius Caesar, after the victory over Ponte, was ordered to carry the famous inscription: veni, vidi, vici, that is: “I came, I saw, I conquered”. Among the ornaments, images of cities and rivers: the Rhine and the Rhone were carried. The ocean is depicted as a young boy painted gold.

Then the spoils of war (armour, weapons, wealth) were taken and prisoners of war (in chains) were led, headed by the kings of conquered countries or the heads of conquered tribes. The next were senators and officials; then likers of the triumphant chief, who had fasces decorated with laurel wreaths. Only behind them was the winner, then immediate family and allies; his disarmed soldiers (dressed in togas and wreaths on their heads) followed, uttering: io trumphe and singing indecent songs about their leader. For example, Suetonius describes how soldiers sang songs in honour of Caesar during his triumph in 46 BCE.

Caesar vanquished the Gauls, Nicomedes Caesar, Caesar who vanquished the Gauls now triumphs. Nicomedes does not triumph, who vanquished Caesar […]

Citizens, keep an eye on your wives, we’re bringing back the bald adulterer. He’s fucked away the gold in Gaul that you loaned him here in Rome. […]

– Suetonius, Julius Caesar, 49, 51

Liberated Roman citizens also walked with the soldiers. Two white oxen (with gilded horns), who were to be sacrificed to Jupiter, also participated in the procession. Along with the bull sacrifice, the public execution (strangulation) of selected prisoners in front of a crowd of Romans took place.

Throughout the triumph, music played, people shouted slogans in honour of the winner, and flowers were thrown along the procession.

After the triumph, the victorious generals organized feasts for the people and separate feasts for the aristocracy at their own expense. Roman writer Marcus Terentius Varro recalls how his uncle earned 20,000 sesterces for delivering feasts after the triumph of Cecilus Metellus over Sertorius in 71 BCE 5,000 thrushes.

Sometimes the triumphs were associated with games (ludi) as an expression of gratitude to the gods; an example is, for example, Marcus Fulwius Nobilior, who combined the two occasions after defeating the Aetolian League in 189 BCE – after the triumph, 10-day games took place.

Ovation

Ovation (ovatio) was a minor triumph awarded to victorious chiefs after the end of their war; often against slaves, pirates or enemies who posed little threat. Ovation, originally was supposed to completely replace the institution of triumph. The latter was perceived negatively at the beginning of the Republic, it was associated with the remnants of the times when it was available only to kings. In the face of the regime change into a republican one, this relic of the old era resembled too much of an old royal feast. Hence the reluctance of the Romans to exalt anyone with an ovation. The tendencies to completely replace the solemn triumph with a more modest form – without a chariot, triumphal robes, a sceptre and a laurel wreath – gave way under the pressure of the aristocracy’s efforts, thanks to which the splendour of the former triumph was restored, without giving up the new form. If the victorious commander did not meet the requirements of a victory qualifying him to triumph, then the Senate could adopt a compromise law and refuse this honour, or award an ovation in compensation.

The first years of the Republic were full of triumphant ceremonies, and there were more and more candidates to apply for this type of award. Hence the a need to introduce certain requirements and conditions, such as the appropriate number of enemies killed or the capture of new areas. It was done so that the glory of the highest honour would not become commonplace and would not lose its importance. Sources mentioning the ovation include fasti triumphales Capitolini and the literary accounts of Livy, Plutarch, Appian and Suetonius. Based on these sources, it is possible to establish the number of about 30 ovations that took place from the beginning of the Republic to the middle of the 1st century CE. From such a modest number it can be concluded that the new form of celebration of victory was not very popular. Triumphs were held much more often and more willingly. For comparison, note that Paul Orosius (c. 385 – 423 CE) gives the number of 320 triumphs from the earliest times to Vespasian.

The ovation took place either on horseback or on foot. The chief was dressed in toga praetexta and carried a wreath of myrtle on his head. Neither senators nor the army of the commander took part in the procession.

The oldest ovation was celebrated in 503 BCE by Publius Postumius Tubertus after his victory over the Sabini. Another ovation was given in 211 BCE by Marcus Claudius Marcellus. We know the course of this event thanks to Titus Livius:

on the day before his entry into the city he triumphed on the Alban Mount. Then in his ovation he caused a great amount of booty to be carried before him into the city. together with a representation of captured Syracuse were carried catapults and ballistae and all the other engines of war, and the adornments of a long peace and of royal wealth, a quantity of silverware and bronze ware, other furnishings and costly fabrics, and many notable statues, with which Syracuse had been adorned more highly than most cities of Greece. as a sign of triumph over Carthaginians as well, eight elephants were in the procession. And not the least spectacle, in advance of the general and wearing golden wreaths, were Sosis of Syracuse and Moericus6 the Spaniard.

– Titus Livius, Ab Urbe Condita,XXVI.21

Octavian Augustus gave a few ovations. Suetonius claims that the first took place after the Battle of Philippi, according to the Capitoline fasts and Dion, in 40 BCE, after making peace with Antony. A second ovation took place during the November Ides of 36 BCE, after the Sicilian victory. In Cicero’s letters, we find information about the third, earlier than the ovation above, although it is not known whether it took place.

During the period from August to Hadrian, six ovations were approved, one of which was ordained by a senator not belonging to the imperial family. Out of the number of six awarded ovations, only three were held. The ovation Germanicus in CE 18 as a reward for the successes achieved in Armenia, where he enthroned Artaxia, did not come to fruition due to the premature death of the young commander. In 21 CE, returning from the campaign Tiberius rejected the ovation passed by the Senate, as he considered it inane praemium (“invalid award”). The honour in question was met in 11 BCE by Drusius the Elder, the brother of Tiberius, who was celebrated in this way for his victories in Germania. Druzus, however, died on his way to Rome, which resulted in his ovation not being held. Tiberius received this type of distinction at the turn of the 8th and 9th CE as a reward for suppressing the Illyrian uprising. In the 40s of the first century CE, a small triumphal entry into Rome was made by Emperor Caligula due to his trip to Britain.

In total, we know 23 ovations from the times of the Republic and 7 from the times of the Empire.