Chapters

| Name | Flavius Theodosius |

|---|---|

| Ruled as | Flavius Theodosius Augustus |

| Reign | 19 January 379 – 17 January 395 CE |

| Born | 11 January 347 CE |

| Died | 17 January 395 CE |

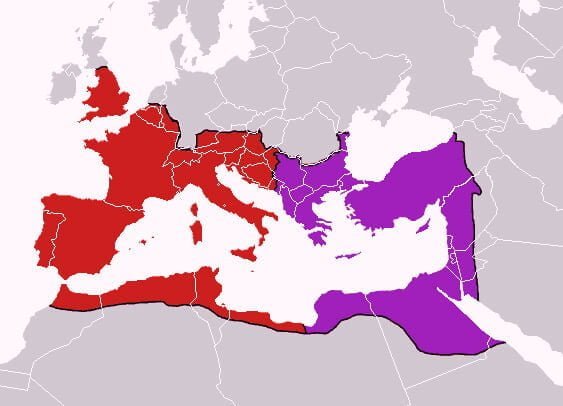

Theodosius I the Great was born on January 11, 347 CE in Spain as Flavius Theodosius (Flavius Theodosius). He was the last emperor to rule both the eastern and western parts of the Roman Empire. He ruled from 379, initially together with Gratian (up to 383) and Valentinian II (up to 392 CE), then independently. During his reign, the Goths settled south of the Danube within the borders of the empire. He was the author of the decrees that recognized Christianity as the state religion in the Roman Empire.

He had two wives. The first, Aelia Flacilla, bore him sons Arkadius and Honorius, and a daughter Pulcheria. After his wife’s death in CE 386, Theodosius married Galla – Valentinian II’s sister – with whom he had a daughter, Gala Placidia.

Background and career

Flavius Theodosius, according to the teachings of Hydatius and Zozimos, was born in Cauca in Gallaecia in Spain or, according to Marcellinus Komes, in the town of Italica in Batica in Spain. He was the son of a prominent Spanish chief, Theodosius the Elder, who was executed under unclear circumstances in 376 CE. Young Theodosius learned his military trade from his father, accompanying him in campaigns in Britain in 367-368 CE suppressing a local revolt.

In about 373 CE, Theodosius was appointed governor of Upper Moesia, where he also oversaw the Roman armies against the Sarmatians and then the Alemans. In 374 CE he was chief (dux) of Moesia, a Roman province on the lower Danube. During his tenure, he lost two legions to the Sarmatians.

Following the unexpected execution of his father in CE 376, he left for Spain. It is believed that Theodosius’ temporary withdrawal from the political life of the country was not forced by Emperor Valentinian I.

The unexpected death of Valentinian in 375 CE caused a serious political crisis in the Roman state. Fearing persecution in connection with his father, Theodosius went to his family estate in the province of Gallaecia (modern Spain and northern Portugal), where he lived temporarily.

Coordinator and independent emperor

The years 364-375 CE are the reign of the brothers: the aforementioned Valentinian I and Valens. The death of the former in CE 375 brought his sons Valentinian II and Gratian to the throne in the western part of the empire. In 378 CE, after the great defeat of the Roman army at Adrianople, where Valens himself died, Gratian decided to summon Theodosius of Spain to take command of the troops in Illyria. As Valens had no successor, the invitation to Theodosius to take command in the East was associated with de facto his appointment in August in the East of the Empire. Despite the help from the West and the increased recruitment to the army in the East, it was not possible to oust the Goths, additionally powered by successive troops arriving from the Carpathian Basin and the Black Sea steppe. Theodosius resorted to diplomacy – he took advantage of the barbarian quarrels, dragged weaker groups to his side and in 382 CE he managed to make peace with everyone. The Goths became foederati – allies of Rome– settlements on the lower Danube, received extensive autonomy but were obliged to provide the empire with soldiers, though only auxiliary troops, fighting under an independent, Gothic, command. These conditions, outrageous for many Romans, allowed to calm the situation on the border and rebuild the imperial army in the East. Theodosius gained great authority among the barbarians, which made them keep their commitments until his death.

After Gratian was killed in a rebellion in CE 383, Theodosius appointed his eldest son, Arcadius, co-ruler in the East. In the struggle for power in the western part of the empire, he backed Valentinian II against Maximus and won a victory in 388 CE. After the death of Valentinian II (392 CE), Theodosius became an independent ruler of both the eastern and western parts of the Empire.

War with Eugenius

When, after the death of Valentinian II in 392 CE, the Frankish leader Arbogast appointed an ex-teacher of rhetoric, a supporter of the pagans of Eugene, to the role of a pretender, Theodosius tightened the prohibition against worshipping any gods, making sacrifices before gods’ images, lighting them with lights, burning incense, and hanging wreaths. He made the examination of the entrails of the sacrificial animals a crime of offending majesty. He ordered all pagan places of worship to be taken over by the state treasury. Any violation of these ordinances was to be punished with severe penalties: judges, city governors and city council members were summoned to execute the decree. When the imperial edict was published in the East, Roman senators, encouraged by Eugene, solemnly resumed their pagan ceremonies. Then Theodosius decided to undertake an armed expedition against Arbogast and Eugene.

In 394 CE he set out with the eastern army into the field against Eugene, who manned the passes of the Julian Alps. On September 6, 394, Theodosius was victorious in the Battle of the River Frigidus when a storm suddenly came from the north. Eugenius and Arbogast died. Nicomachus, who received the prefecture of Italy from the usurper, died during the war. His son, who was the city’s prefect, sought refuge in the church, was forgiven, and converted to Christianity. Theodosius entered Rome victorious and showed grace to the survivors. He also felt that this was a great time to appoint his second son, Honorius, co-ruler in the West. On January 23, 393 CE, he made a conciliatory gesture to the senate, whom he introduced as the successor to his younger son, Honorius. Of course, the senate accepted the proposal.

Defeating the usurper Eugene in the Battle of the Frigidus River restored peace to the Empire.

Faith and Religious Policy

From the beginning of his reign, Theodosius was consistently on the side of opponents of Arianism and against the pagan faith. Under the influence of the Bishop of Milan – St. Ambrose – an enemy of Arianism, he was the promoter of the Nicaea confession of faith. On February 28, 380, he issued a law known as the Edict of Thessalonians, in which he wrote:

It is our desire that all the various nations which are subject to our Clemency and Moderation, should continue to profess that religion which was delivered to the Romans by the divine Apostle Peter, as it has been preserved by faithful tradition, and which is now professed by the Pontiff Damasus and by Peter, Bishop of Alexandria, a man of apostolic holiness. According to the apostolic teaching and the doctrine of the Gospel, let us believe in the one deity of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, in equal majesty and in a holy Trinity. We order the followers of this law to embrace the name of Catholic Christians; but as for the others, since, in our judgment they are foolish madmen, we decree that they shall be branded with the ignominious name of heretics, and shall not presume to give to their conventicles the name of churches. They will suffer in the first place the chastisement of the divine condemnation and in the second the punishment of our authority which in accordance with the will of Heaven we shall decide to inflict.

Under this law, heresy became a crime prosecuted by the state. In January 381 CE, Theodosius decreed that heretics (some were mentioned by name) had to hand over their worship premises to orthodox bishops. Heretics could not ordain their clergy; those who had already been ordained were denied their ecclesiastical dignity. They were not allowed to teach their faith or hold synods. Following the introduction of the Edict of Thessalonian, adherence to the traditional pagan religion was punishable by the confiscation of property and death. Thus, in 381, all pagans and heretics were removed from office. In 382, by order of Emperor Gratian, the statue of the goddess Victoria was taken out of the Senate’s meeting room.

In 381, the matter of religion in terms of church jurisdiction was also settled throughout the empire. An ecumenical council called on May 1, 381 CE in Constantinople, which, inter alia, was to settle the dispute over certain bishop’s churches, he adopted a formula which, by adding the Holy Spirit, made the symbol of Nicaea a confession of faith in the Holy Trinity. Further decisions of the council adjusted the church organization to the structure of the empire even more than before. The bishop, whose seat was the capital of the state diocese, was given priority over other metropolitans. The bishop of Constantinople was to occupy a position behind the bishop of Rome, because his city was “the second Rome”.

Although Theodosius opened the assembly of the Council of Constantinople in the parade hall of his palace, he did not participate in its further deliberations, overseeing what was happening from a distance. After closing the session, the emperor confirmed the council’s decisions with his edict.

Soon the emperor issued further executive orders to the basic law: heretical churches were ordered to be attached and the Manichaeans were deprived of the right to profess their faith. In order to solve other questions, there were synods in Constantinople in 382 and 383 CE. On the occasion of the second, an attempt was made to persuade heretical leaders to agree. As this failed, the religious formulas of the heretics had to be submitted to the emperor for decision. Theodosius, however, tore up the petitions in front of the authors.

In 388 CE, Theodosius forbade public discussion of doctrine. Heretics had drastically limited civil rights. If they belonged to the elite, they lost their state privileges and their right to hold office. Their ability to pass property through a will and accept legates was also limited; nor could they be legal guardians. The situation of the apostates was similar. The Manichaeans and their related groups mentioned in the law were subject to more severe repression: they were removed from the empire, and those who dared to return faced the death penalty.

At the emperor’s initiative, systematic enforcement of earlier laws on the closure of pagan places of worship in those places where these laws remained a dead letter was started. The symbol of the defeat of paganism was the destruction of Serapejon in Alexandria, a famous and supposedly very beautiful sanctuary. E-hulhul (House of Joy) – the main temple of the god Sin in Harran (c. 382) was also demolished. The rights of the Jews were also restricted.

Theodosius zealously strengthened the position of the Orthodox Church through legislative activity, rather he supported church matters. This kind of patronage from a distance, backed by legislation that was in line with the intentions of the leaders of the Catholic Church, generally suited them. However, not everything Theodosius did was in keeping with their position. The emperor tried to limit the scope of the church asylum, excluding from it certain categories of criminals (especially debtors of the state treasury), and also to reduce the scope of church interventions in the field of the judiciary. The law ordering the monks to leave the cities, although it was well suited to many bishops facing difficulties with an unmanageable anarchist element, could not arouse enthusiasm in such a radical form; not everywhere were monks frowned upon by the clergy.

Theodosius gradually pushed Rome’s traditional beliefs away. In 391 CE he issued a strict prohibition on sacrificing, visiting temples, and worshipping statues. In 392 CE (other sources mention 380 and 395) banned religion other than Christianity, raising it to the status of the state religion. He forbade the organization of the ancient Olympic Games in 393 CE as a relic of paganism. These decrees are known as theodosian decrees.

Penance of Theodosius

In 388 CE, Theodosius learned from a report by the Comes Orienti that at Callinikum, in Mesopotamia, monks had encouraged a crowd of Christians to destroy a synagogue and a chapel belonging to the Valentinian sect. The emperor ordered the bishop of Kallinikum to rebuild the synagogue. Bishop Ambrose reacted very harshly, declaring that he would not celebrate the Holy Mass in the presence of the Emperor if he did not cancel the order. Theodosius relented.

In 390 CE, on the orders of Theodosius, there was a massacre of the people of Thessaloniki. Earlier, the emperor issued a law providing for the death penalty for homosexual sex. On its basis, the magister millitum, the commander of the Buteric troops, ordered the arrest of a circus coachman who had openly engaged in homoerotic sex. It ended in tumult and the death of Buteric. The emperor wanted to discourage the population of other cities from similar acts and ordered bloody repression. Bishop Ambrose admonished him and insisted that the order be revoked, to which Theodosius agreed, but this decision reached Thessaloniki post factum. In the summer of 390, the emperor appointed Nikomacha Flavian, a well-known pagan, to the position of the praetorium prefect. In June, he issued a law on deaconesses, which, by prohibiting them from holding this function before the age of 60 (in accordance with church regulations), did not allow them to make testamentary legates for the Church, clergy or the poor if they had children of their own. As a result of Ambrose’s objection, Theodosius sent the imperial dignitary Rufin to engage in talks with Ambrose. In August, the emperor issued a law ordering the execution of convicts only 30 days after the sentence and, also in August, he cancelled the law on deacons. He appointed pagan consuls for the next year, and on September 2, he signed a law prohibiting monks from staying in cities. In the end, however, he accepted Ambrose’s conditions, and after repentance, he was re-admitted to the group of the faithful. This happened on Christmas 390 CE

Death and the Permanent Division of the Empire

Emperor Theodosius I died in Milan on January 17, 395 CE as a result of complications due to severe swelling. After his death, Bishop Ambrose gave a panegyric entitled De Obitu Theodosii to Flavius Stilicho and Honorius, in which he praised Theodosius’ suppression of paganism. Theodosius was buried in Constantinople on November 8, 395 CE.

His successors were sons: 10-year-old Honorius in the West (Latin-Romanesque part) and 18-year-old Arkadius in the East (Greek part). None of them showed great management skills. As if feeling that both of them would not be able to effectively rule their parts, Theodosius appointed them Stilicho’s guardian. This de facto ruled the Western Empire on behalf of Honorius; in turn, in the East, Flavius Rufinus dominated.

Are you really big?

To this day, it is commonly referred to as Theodosius I, founder of the Theodosian Dynasty, “the Great”. This nickname was given to the ruler by Christians, who during his reign finally triumphed throughout the Mediterranean world. At present, however, it is difficult to conclude that Theodosius deserves such a nickname. His barbaric politics, marked by hostility to ancient Roman cults and traditions, make him believe that the emperor has severed his roots with the entire history of the Roman Empire. The prohibitions on cultivating the native faith in the public sphere were gradually extended to the private sphere. It was forbidden to burn incense or pour liquids in honour of the Lara or the Genius. The emperor agreed to destroy pagan temples and statues of gods. The aforementioned ban on the organization of ancient games only confirmed which ideology guided the actions of the ruler.

Theodosius cannot be denied leadership and management skills. His decisions strengthened the state during his reign. The division of the Empire in 395 CE was the result of historical processes and only confirmed that a country with such a large area and administrative weakness was not able to survive in a combined form. There had been divisions of the Empire before; this time, however, the separation was permanent.