Chapters

Sertorius was a Roman commander and politician living at the turn of the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE, who opposed the Roman war machine. Due to his belonging to the popular camp, he was forced to leave Rome and finally headed the Iberian tribes and resisted in the 80-73 BCE.

Background of events

The beginning of the 1st century BCE heralded an extremely bloody century for the Roman Republic. The political division into optimates (supporters of maintaining power by the elite and rich) and popular (supporters of reforms and improving the fate of the lower classes) led to a strong destabilization of the Roman state. The rivalry of ambitious politicians Lucius Cornelius Sulla and Gaius Marius formed strong divisions in Rome, which resulted in bloody clashes of supporters in the streets, murders, legions marching on the capital and the assumption of an unlimited dictatorship by Sulla.

Sertorius

Sertorius (Quintus Sertorius) was a Roman commander and politician who lived in the years 126-73 BCE. He had the status of equestrian. He came from central Italy, and his political career was associated with Gaius Marius, leader of the popular party and main rival of Lucius Cornelius Sulla (optimates). Under Marius’s orders, he served in the war against Cymbrom and Teutons. In 98 BCE he fought as a military tribune in Spain during the Social War (helium sociale, 90- 88 BCE), where he commanded one of the Roman legions.

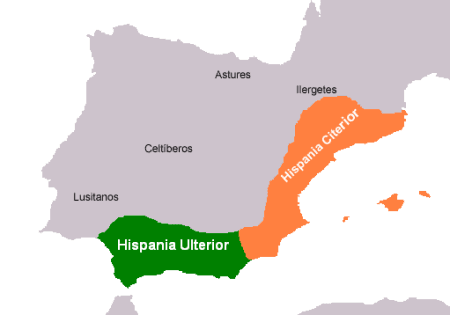

During the Civil War in 87 BCE, he was a member of the popular party and one of the four Marian leaders. In 83 BCE he was to take over the governorship of the Province of Closer Spain (Hispania Citerior). This was to force him to leave Rome, where he was to become a consul. Before he could leave, however, the nomination was withdrawn by the senate dominated by the optimates. Sertorius gathered a small detachment of followers with whom he travelled 82 BCE to the Iberian Peninsula, where he gained the support of the Celtic tribes. With time, however, under pressure from Sulla’s commanders, who sentenced him to death, he was forced to leave Spain. He took refuge in what was then Moorish Morocco, where he fought in the local war in the city of Tangier and from where he made an expedition to the Canary Islands.

Uprising in Spain

In the first century BCE, the Iberian tribes, subordinate to Rome, felt the yoke of the Empire more and more strongly. The Iberians were forced to constantly supply their fighters to Rome’s numerous war campaigns. Moreover, Spanish communities complained about Roman tax collectors or moneylenders who plundered them mercilessly. The tribes were forced to pay for the Roman legions stationed on the Peninsula, what’s more, without having the status of Roman citizens.

The Lusitanians sacrificed prisoners, their entrails were used for divination. In addition, Strabo, a Greek geographer and historian, describes the Lusitanians in “Geographia” as a people drinking beer, using butter and baking bread from ground acorns, based on the work of Artemidor.

One of the more rebellious peoples was the Lusitanians, who occupied the central-eastern part of Spain. After long resistance, they were conquered by Rome in 139 BCE and were gradually romanized. The widespread hatred of the Romans and the internal divisions in the Roman state encouraged them to look for a “better future”. To this end, in 80 BCE, the Lusitans sent emissaries to Sertorius with a proposal to return to the Iberian Peninsula from Africa. He was to lead the uprising against Rome, under the authority of Sulla. Sertorius, unable to count on an amnesty, probably decided that using Lusitan’s independence aspirations was the best solution for this situation. He believed that this way he would defeat Sulla’s camp.

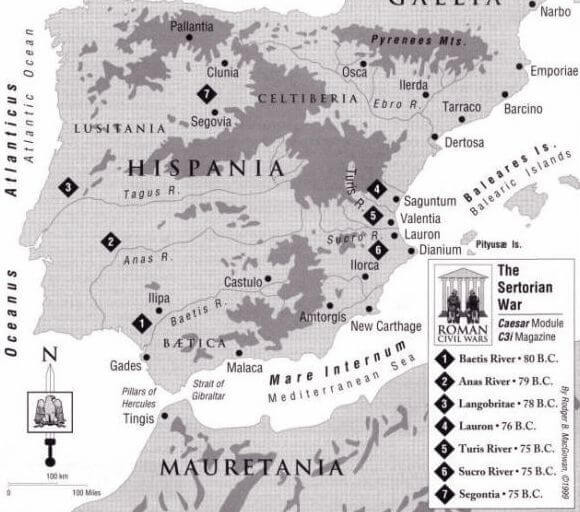

Sertorius, after the destruction of the Roman fleet of Gaius Aurelius Kota, landed on the Iberian Peninsula. According to Plutarch, he first went to Lusitania to organize the tribes there, and then rushed into battle. Sertorius’ forces defeated the Roman army led by Fulfidius in the Battle of the Guadalquivir (some historians, such as Philip Spann, claim that the battle took place during the march to Lusitania).

Sertorius, having appeared on the lands of Lusitan, set about organizing an independent state. He made the city of Osca (now Huesca) the capital of this political entity. Following the example of the Roman system, he created the Spanish senate, which, however, included representatives of the expelled Romans. He entrusted some of the command positions in the army to local leaders and princes, which also managed to gain the support of part of the Spanish aristocracy. Sertorius exempted the natives from some taxes, reformed the courts and, most importantly, founded a school for children and youth of local nobles. This step significantly accelerated the romanization of the province, despite the fall of the uprising.

Concerned by the growing threat, Sulla decided to appoint their best chief and the current consul Quintus Cecilius Metellus Pius as proconsul and give him governing powers in Further Spain (Hispania Ulterior). Pius established the city of Metellinum (now Medellín) as his base and launched attacks on the areas occupied by the rebels led by Sertorius. Despite efficient operations, all attacks were repulsed, and the Roman army additionally had to deal with extensive guerrilla activities. Moreover, Sertorius enjoyed enormous popularity among local tribes.

In the two years of fighting, the proconsul Metellus Pius and his army were devastated. In addition, Sertorius’ subordinate, Lucius Hurteleus, defeated the army of Marcus Calvinus Calvinus. Sertorius has proved his military genius. Successive armies sent by the Senate could not match the rebels in the field. Sertorius bravely faced them both in the open field and in a guerrilla war, tearing Roman ranks and cutting off the Roman legionaries’ food supply, and sometimes even pay.

Soon, Sertorius’ forces, strengthened by Sulla’s opponents escaping from Italy, mainly popular, took over a large part of Spain. Mark Perperna’s troops, once part of the army of Mark Emilius Lepidus (consul for 78 BCE), arrived from Sardinia. At first, Perperna was reluctant to come under the command of Sertorius. However, with news of the coming troops of 29-year-old Gnaeus Pompey (summoned to help by Pius), his men forced him to officially support the rebels in 77 BCE. Moreover, Sertorius he made an agreement with the King of Pontus, Mithridates VI Eupator, fighting at the same time with the Romans in Asia Minor; sources say that he sent to the king of Pontus an army unit commanded by Marius, who was the commander of the Aegean fleet of the ruler of Pontus.

Plutarch tells us Sertorius’ dismissive attitude towards his younger Pompey:

Thereupon Sertorius disseminated haughty speeches against Pompey, and scoffingly said he should have needed but a cane and whip for this boy, were he not in fear of that old woman, meaning Metellus. In fact, however, he kept very close watch on Pompey, and was afraid of him, and therefore conducted his campaign with more caution.

– Plutarch, Pompey, 18

Pompey, after arriving in Iberia, decided to first clear the coastal roads and deal with the charges of Sertorius. Many settlements so far neutral and even supporting Sertorius began to recognize the power of Pompey, who was a respected commander despite his young age. The city of Lauro1, which Sertorius immediately moved to, passed over to Pompey’s side. It was to be the biggest clash of war in Spain.

Battle of Lauro

Based on the accounts of Plutarch of Chaeronea (Sertorius) and Frontinus (Strategemata), we know that Sertorius set up a camp on a hill near the city, and Pompey a short distance from him. Sertorius, however, set a trap for his rival, dividing the army into two parts, wherein one, three legions and 2,000 cavalry, commanded Hirtuleius.

Pompey, after several days of waiting, began to experience food shortages. He decided to send one legion to provide supplies; however, returning the next day, he was attacked and cut down by the army of Sertorius. A similar fate befell the auxiliary unit, which was also killed. Pompey finally decided to leave the camp and fight, which ended in defeat, as his legions were surrounded on both sides by the troops of Sertorius and Hirtuleius. Pompey lost a total of almost 10,000 people and was forced to withdraw and recognize the advantage of his rival. Sertorius captured the city and burned it, and the people displaced to Lusitania.

Interestingly, Appian of Alexandria left us with an interesting story that was to take place during the conquest of the city of Lauro by the soldiers of Sertorius:

In this siege a woman tore out with her fingers the eyes of a soldier who had insulted her and was trying to commit an outrage upon her. When Sertorius heard of this he put to death the whole cohort that was supposed to be addicted to such brutality, although it was composed of Romans.

– Appian of Alexandria, Bella CiviliaI, 109

In 75 BCE Pompey managed to defeat the legates of Sertorius: Perperna and Herennius at Valentia (now Valencia), where the second of the chiefs were killed. At that time, Metellus Pius defeated Hurteley, who died in battle, in the battle of Italica. Despite the great will to fight, the forces of the insurgents began to run out. The Romans had almost unlimited access to human resources and enormous funds. The Spanish tribes realized this. Despite their bravery and courage, they were not able to compete with the Roman war machine.

Sertorius, upon the news of Hurteley’s defeat, decided that a battle should be brought about with Pompey’s army, before they could merge with the army of Metellus Pius, which was coming from the west. The Battle of the Sucro River which took place in 75 BCE ultimately did not provide a solution, as both one of the wings of Sertorius and Pompey withdrew from the battlefield under pressure from the enemy. Sertorius’ forces then faced the combined armies of Metellus Pius and Pompey, possibly near Saguntum(now Sagunto). In the end, Sertorius’ army was defeated. Sertorius withdrew to the well-fortified city of Clunia and bound the Pompeian forces. Thanks to this treatment, other divisions of Sertorius were able to rebuild and merge.

In 74 BCE Pompey and Metellus Pius waged warfare in the lands of the Celtoiber, and Sertorius gradually lost his influence. The mood in the rebel army worsened and the insurgent camp began to divide. Marcus Perperna, still unable to accept the role of the “other”, gradually criticized Sertorius more boldly. Perperna was backed by a section of the Roman elite who was unhappy with equating the Romans with “barbarians.” In addition, the Roman Senate passed an amnesty for all political fugitives, which thinned the ranks of Sertorius’ army. Sertorius, seeing the inevitable end of the fight, tried to introduce severe discipline in the army, which had already undermined his authority.

In the years 75-73 BCE the army of Pompey and Metellus Pius managed to oust Sertorius as far as the Ebro River valley. Then the pirates cooperating with Sertorius offered him transport to the so-called “Happy Islands”, which are equated with the Canary Islands. Sertorius was to consider this possibility but finally decided to fight.

Eventually, Marcus Perperna plotted against Sertorius in 72 BCE and killed the leader. Perperna himself was lured into a trap with the army, captured by Pompey and killed by Pompey. Plutarch gives the reason:

For Perpenna, who had come into possession of the papers of Sertorius, offered to produce letters from the chief men at Rome, who had desired to subvert the existing order and change the form of government, and had therefore invited Sertorius into Italy. Pompey, therefore, fearing that this might stir up greater wars than those now ended, put Perpenna to death and burned the letters without even reading them.

– Plutarch, Pompey, 20

Consequences

According to historian Howard Hayes Scullard, Pompey’s victorious troops showed a humanitarian approach to the defeated. Many of the optimists’ supporters were granted citizenships when the die-hard opponents were merely displaced to the Lugdunum Convenarumin southern Gaul.

After crushing a long rebellion in Spain, Pompey returned to Italy, where he supported Crassus in the liquidation of the Spartacus slave uprising. He was then awarded a triumph in Rome for his achievements.

In fact, the war of Sertorius was the last uprising of independence for the Spanish tribes. From that moment on, it was possible to talk about the consolidation of Roman authority in the region and the increase in the influence of native Iberians on the internal policy of the Roman Empire.