In the final period of the existence of the Roman Republic, violence became an integral part of politics. In the period under discussion, it was mainly the responsibility of Publius Clodius and Titus Milo. However, apart from them, another politician, Publius Sestius, also played a role in the fighting in the streets.

Sestius was born in the 90s of the 1st century BCE. He assumed his first public office in 68 BCE when he was elected a tribune. In the following years, he continued his career, becoming a quaestor in 63 BCE. This year, Sestius developed a close relationship with Cicero and began spying on Gaius Antony for him, suspected of collaborating with Catilina. Cicero appreciated his merits in this field so much that he mentioned him in his speech on November 8 (he described him as “a wonderful young man”). When, after defeating Catilina, Antony went to Macedonia, Sestius followed him. He did not return until 60 BCE

He returned to politics two years later – on December 10 he took the office of the tribune. One of his first activities was to present a project to restore Cicero from exile, which once again won him the favour of the orator. It was then that he got involved in fighting in the streets. Publius Clodius – who benefited greatly from Cicero’s exile – tried to stop Cicero’s pardon. To this end, at the head of a group of gladiators on January 23, he attacked the People’s Assembly – before it was able to accept the request. To stop further acts of aggression by Clodius, Pompey ordered Titus Milon and Sestius to organize their own armed groups. It was with the activities of these groups that the Sestius trial of the following year was connected. On February 10, 56 BCE, Sestius was accused by a certain Mark Tullius (of course, he had no connection with Cicero) of political violence. The defence of Sestius was undertaken by Cicero himself, supported by Hortensius and Crassus.

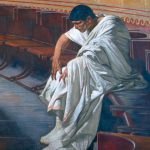

During the trial, the prosecutors were to be Publius Albinovanus and Titus Claudius. The indictment line was based on the assumption that Sestius had organized an armed group with the intention of robbery. To prove this, the prosecution called Publius Watinius as a witness. In addition to his own testimony, he presented Sestius’ public and private statements to prove that he had planned an open fight with Clodius from the beginning. Moreover, Albinovanus and Claudius compared Sestius with Milo and pointed out that Milo initially tried to communicate with Clodius. In their opinion – since Sestius did not do it, it should be concluded that he had to strive for confrontation from the very beginning. In this situation, Cicero decided to partially agree with the accusers. Instead of denying all the accusations, he decided to present Sestius’ creation of his “gang” as justified. To this end, he presented it in court as an act of self-defence of Sestius, who – attacked by Clodius’ people – was to fear for his life. Additionally, he presented all the actions taken by Sestius, i.e. attempts to ensure Cicero’s return to Rome and the fight against Clodius as actions for the good of the state. To this end, he recalled the memory of the radicals gathered around Catilina and argued that Clodius was, in fact, a continuator of their activities. To support this argument, he called as a witness, inter alia, Pompey, which surely gave him additional favour from the judges. Cicero also referred to specific events in Clodius’ life, such as the attack of his people on Cicero himself or the scandal with the Mysteries of the Good Goddess.

Ultimately, Cicero’s speech, which went down in history as “Pro Sestio”, led to the acquittal of Sestius. In the years that followed, he continued to be a supporter of Pompey and remained so until the outbreak of the Civil War, when he became governor of Cilicia. Sestius, however, betrayed Pompey shortly after the outbreak of the war and went to Caesar’s camp. One of the last pieces of information about him is that in 48 BCE he was sent by Caesar to Cappadocia.