Chapters

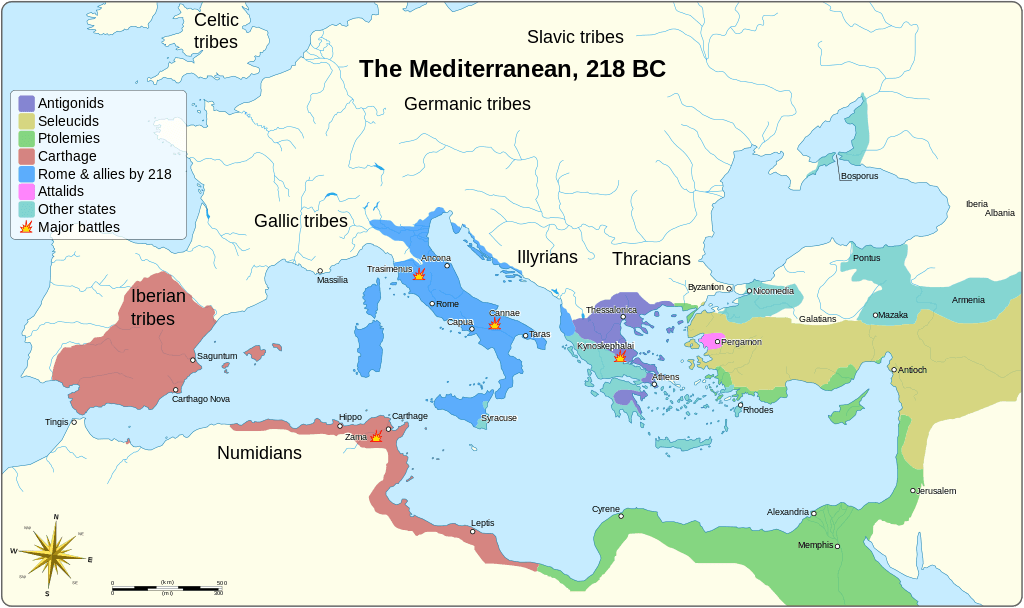

During the third century B.C.E Rome continually fought other Mediterranean states. The end of the First Punic War left the Punic empire considerably lessened, and many Carthage’s nobles disgruntled with the peace treaty and expansion into Spain. The resulting clash with Rome influenced both the republic and other states that were in conflict with it at the time, e.g. Macedonia. Hannibal’s victories over the legions convinced the Macedonian leader that Romans can be beaten and routed and that an alliance with victorious Carthage would be politically advantageous.

Historical background

The king of Macedonia, Philip V, had been watching the growth of Roman influence along the Illyrian coast with growing concern. Following their successful expeditions against Illyrian pirates in 229 and 219 B.C.E, the Romans forged Alliances with multiple settlements in the area, including Lissos and Apollonia. Moreover, the senate kept inciting Scerdilaidas, the Illyrian ruler of the Ardiaean Kingom, against Macedonia. Already in the summer of 217 B.C.E Scerdilaidas impounded Macedonian ships near Leukas against an alleged payment being due from Philip. His next move was to invade Pelagonia and Dassaretia as well as ravage northern Macedonia.

The presence of Roman emissaries among the Illyrian tribes at the time of that invasion was no mere coincidence. The audacious raid was soon repelled by Philip, who took back the invaded lands and thus almost became a neighbour of a Roman protectorate. News of difficulties faced by Rome in Italy, particularly of defeat at Lake Trasimene, prompted Philip to grab Roman lands in Illyria. The King was further incited by the suggestions of Demetrius of Pharos who was present at the court in Pella at the time. However, in order for the undertaking to be successful, Philip needed a large war fleet. Therefore the King brought in Illyrian shipwrights, who immediately commenced the construction of 100 agile lemboi (skiffs), enough to transport 5 000 soldiers. In the summer of 216 BCE Macedonian fleet took to the sea for necessary drills. Afterwards, it sailed around the Malea peninsula in Peloponnese and moored near the islands of Leukas and Kephallenia, where the king learned from his spies about the presence of Roman fleet near the western shores of Sicily. Philip dismissed the threat and sailed north in order to take Apollonia, one of the chief settlements of Roman protectorate. By seizing the city he intended to secure the lines of communication with Macedonia and to bring additional fresh troops. As the Macedonian fleet neared the city walls, news were brought about the movements of Roman armada, which by that time was reported at the city of Region on the coast of Italy. Apparently Scerdilaidas, stunned by Philip’s actions, requested Roman assistance, which was promptly granted. Upon hearing the news Philip cancelled the assault and swiftly withdrew the ships to Kephallenia. His stance was changed again by the news about the rout of Roman army at Cannae on the 2nd of August 216 BCE Philip became convinced that utter defeat of the Republic is only a matter of time and decided to take advantage of that by obliterating Rome’s assets on the Adriatic coast. This plan was to be brought to fruition by an alliance with triumphant Hannibal.

Macedonian-Carthaginian cooperation treaty

First contact between the interested parties was made at the turn of 216 BCE, and in the summer of 215 BCE Philip sent envoys to Hannibal in order to sign the treaty of cooperation. The legation was led by an experienced commander, Xenophanes of Athens. Landing in Brindisium or Tarentum was out of the question as those sections of Italian coast were being patrolled by Roman squadrons, therefore the envoys disembarked only at the tip of the Italian ‘boot’, near the town of Crotone, manned by Hannibal’s troops. They gathered from the locals that Hannibal is camped near Arpi in Apulia. On the way, however, the legation was intercepted by Romans and brought before praetor M. Valerius Laevinus. Fortunately, Xenophanes showed great presence of mind and told Laevinus that the legacy is headed for Rome in order to secure a friendly treaty.

Laevinus professed his satisfaction with the mission, assigned the ambassadors an escort and sent them on their way. As information from Laevinus included the location of both Roman and Carthaginian camps, the envoys easily reached Hannibal and sealed the treaty. On the return trip, however, Xenophanes ran out of luck. Philip’s envoys were recaptured and brought to prefect P. Valerius Flaccus. This time the cunning Xenophanes could not mislead the prefect, as the legacy now included Punic envoys, conspicuous by their speech and apparel. Thus the Romans found themselves in possession of a copy of the treaty as well as Hannibal’s letter to Philip. Sometime later the king of Macedonia sent another legation to Italy, which confirmed the treaty valid and returned without setbacks.

The document was concerned with relations between Carthage, its subjects and allies in Italia, Liguria and Gaul, and king Philip and other countries of Hellenic Symmachia allied with him. Both interested parties vowed to support each other against Romans if necessary, according to further stipulations, until victory was achieved. In the event Romans, or any other nation, declares and commences war upon any of the signatories, the other party was bound to support the defenders within its capabilities. One notable point is a stipulation regarding territorial transformations on the coast of Adriatic. The treaty specified that in an event of Roman defeat, they must forgo the ownership of Corcyra, Apollonia, Pharos, Epidamnos, Dimale, Parthus, and Atintania. It is evident that Hannibal did not intend Rome to be destroyed altogether but only significantly reduced, possibly to the territorial extent of Latium.

Experts disagree whether Philip planned to invade Italy itself or if he would only dismantle Roman settlements in Illyria. In light of imprecise stipulations of the treaty, missing details regarding military cooperation in juxtaposition with precise territorial aspirations of the Macedon, it may be inferred that Hannibal wished to keep its ally well out of the Italian war theatre. Apparently Philip was merely to keep a part of Roman forces engaged away from Italy, as the Punic leader wished to bring war to Sicily and Sardinia. However, at some point of the conflict the Macedonian king was able to actually land his forces in Italy, as clearly he understood that it was there that the fate of his kingdom will be decided after the alliance with Hannibal is signed. Moreover, Hannibal himself could be in need of Philip’s help as the Romans took back the initiative.

Significance of the treaty

The Romans responded swiftly. The Quirites declared “Just war” on Philip and the Hellenic Symmachia allied with him, thus accusing the Macedonian king of causing the conflict. According to Livius, the Roman squadron under the command of prefect Valerius Flaccus was increased from 25 to 50 ships. Their crews were to be supported by crews stationed in Tarentum. Prefect Flaccus was charged with careful scrutiny of Macedonian movements across the Adriatic. In the event that Philip’s intentions to invade Italy were confirmed, the command of the squadron was to pass to praetor Valerius Laevinus. Next, a Roman force was to land on Macedon shores with orders to contain Philip within the borders of his kingdom.

According to Livius, in the autumn of 215 BCE praetor Laevinus was sent to Brundisium in order to repel a potential Macedonian invasion. His forces consisted of 2 legions which arrived from Sicily and were later reduced to 1 legion, which was still augmented by strong navy. Having learned that Philip had moved against Apollonia and Oricum, Laevinus sent a relief force to the latter city. Roman landing force took Oricum and placed a strong contingent in the settlement. Next the Romans sent a part of their force to Apollonia. The legions entered the town by night and launched an excursion against the poorly defended Macedonian camp. Romans also gained allegiance of Macedonia’s chief enemies in Greece, the Etolians, by signing a treaty with them in 211 BCE against Macedonia. The treaty was open to the possibility of joining the alliance by other Greek states hostile to the Macedon, like Elis, Sparta or Pergamum.

Some researchers are of the opinion that it was wrong of Philip to join the seemingly victorious Carthage. He would have done better if he kept his neutrality, instead of risking Roman retribution against himself and other Hellenic states. However, taking into consideration common diplomatic practice of the Roman Empire, such claim can be only partially validated. Even if Macedonia had stayed neutral during the war, it seems likely that the patres would find some pretext to assault the Hellenic East. Warlike and expansionist, Roman Republic was in this respect no different from other antique states, but there can be no doubt that the patres never forgave Philip for “backstabbing” them when their country was facing complete obliteration. Afterwards Philip, in the eyes of Roman public, became a synonym of a jackal and hyena, which sped up action against him considerably and precipitated First and Second Macedonian War.