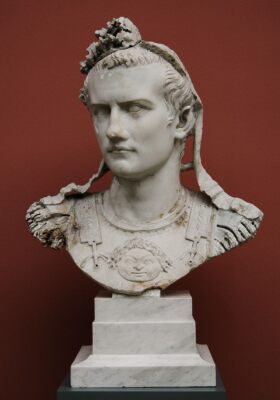

Antiquity abounds in many colourful characters with interesting lives. Both positive and negative. There is no shortage of statesmen, warriors, chiefs as well as torturers, psychopaths and deviants. One of such characters is undoubtedly Caligula, actually Gaius Iulius Caesar Germanicus.

It was assumed that he was a bloody sexual pervert, which was probably influenced by the famous film adaptation from 19791, as well as the general belief (rather resulting from some part of the historiography) that our hero was such a degenerate. Of course, there is a bit of truth in these performances, but let’s take a closer look at his biography and try to answer how big is that bit.

Before I deal with the figure of Caligula for good, I will outline in a few sentences the reality of the era in which our hero lived. Caligula was born on August 31, 12 CE in the Roman Empire, the largest empire in the world at that time. The Roman legions still ruled the ancient battlefields. But significant changes took place at that time in the very structures of the Roman state. The political events that took place in the first century BCE led to political turmoil (including the civil war), and consequently initiated the process of changing the political system from republic to empire. As usual in such cases, we observe a fierce political struggle at the top of power. Also, poisonings, assassinations, and the like were nothing unusual and strange. Bloody gladiatorial fights and public executions were the daily bread of an inhabitant of ancient Rome. Therefore, when assessing the figures of that era, we must keep this in mind. In most of the studies and information, Caligula is presented in an extremely negative way, as an indomitable deviant and an idiot who is insane. Roland Auguet in the biography of Caligula presents him, however, as a politician who is inexperienced, but far from madness or psychosis. I will try to analyze these views.

Caligula was born in the family of the famous commander Germanicus. He gained his nickname Caligula when, as a small child, he wore a soldier’s outfit made especially for him, and it was so accurately reproduced that he also wore miniature soldier’s sandals2. Caligula’s father was a very popular person among the Romans, and especially among soldiers. He waged campaigns against the Germans but with varying luck. Eventually, he was fingered in the Middle East by the reigning Emperor Tiberius. So I think that young Caligula was brought up by his father to be an enlightened statesman and military commander. Unfortunately, Germanicus himself was not able to complete his son’s education. He died suddenly when Caligula was only 7 years old. Undoubtedly, the emperor feared his popularity and growing influence, which was probably the reason for his dismissal from Germania and sending him to the east. We have strong grounds to claim that the death was not natural (most historiographers say that he was poisoned by Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso – the governor of Syria). Germanicus made no attempt to reach power despite the occasion. However, it is highly likely that this did not convince Tiberius, who feared his growing popularity, especially in military circles. These fears were not unfounded, as the news of his death mourned him in crowds in the streets. Caligula’s mother, Agrippina the Elder, immediately after the death of her husband became an opponent of the reigning emperor. An opposition dissatisfied with the rule of the ruling ruler gathered in her house3. Young Caligula grew up in such realities. Of course, Agrippina’s attitude could not be without consequences, and she and her family became the subject of an investigation at the behest of Tiberius. It was led by the emperor’s henchman at the time, Sejanus. A ruthless and ruthless man, which he soon paid with his life4. He gathered numerous testimonies against Caligula’s mother, mostly denunciations and false information, which were also provided to him by senators and the aristocracy, which may later imply such hatred of Caligula towards the above institutions. As a result of the proceedings, Caligula’s mother and brothers were sent into exile, where they soon ended their lives. Caligula never forgot or forgave it. Caligula himself was placed on Kapri next to Tiberius – the murderer of his family, where he stayed until his death. He was forced to pretend that he did not care about the fate of his family. The fact of death and succession after Tiberius is presented in various ways. Caligula is accused here of hastening the death of the ruler and strangling him with a pillow while he was lying sick in the bed. I think it is probable, but it seems to me that it is more important that he made an alliance with Makron, the praetorian prefect, which would enable him, with his help, to succeed Tiberius without any problems (you can read in the sources that he and Macron choked Tiberius5). This shows eloquently that during this period he thought very logically and in perspective, creating alliances so necessary in politics. Interestingly, the seal of this alliance was the relationship with Macron’s wife, which may illustrate how sexuality was perceived in Rome at that time, it was not as taboo as it is in today’s era.

Caligula became emperor. One of his first actions was going to the place of exile for his mother for her ashes. The sources here agree and emphasize that despite the stormy season and high risk, the young ruler went on a journey immediately6. In my opinion, this proves that he had great affection for my mother, which may later explain such a far-reaching hatred for the senate and for people who participated in the process of persecuting her. He also demolished the property where she was imprisoned, wanting to erase from the world every trace that could remind of the persecution of his family, and also to emphasize that he condemns and dissociates himself from the politics of his predecessor. Apart from the young emperor, his three sisters – Agrippina the Younger, Julia Drusilla and Julia Livilla – also left the family slaughter.

Apart from the administrative and political actions, about which Caligula is about to do one more symbolic act. He had a bridge built (something like a pontoon bridge that required tremendous resources and engineering creativity) from cargo ships in Baja Bay. According to most authors, this gesture shows undoubtedly mental disorders in the young emperor. Auguet explains here7, however, quite convincingly that it was possibly a test of strength with earlier great rulers Xerxes8or Alexander the Great. In addition, during the proud crossing of the bridge, he was accompanied by Parthian hostages, with whom the empire undoubtedly had a big problem, which, according to Auguet, was to show them the power of the Roman state. I believe that one more factor was very important. We have records that the dream of Tiberius was known, which proclaimed that Caligula would become emperor when he crossed the Bay of Baja on horseback. Considering how superstitious the Romans and ancient civilizations were, I would see this fact as the cause of this extravagance. He organized this show before his illness, which was to be the beginning and the reason for the change of the ruler’s behaviour, which in a way refutes this cause.

I will now present the administrative and political activities at the beginning of the reign of the young emperor. Undoubtedly, they started very promisingly for the people of Rome. Caligula burned the case file for the persecution of his mother, publicly promising that he would not take any consequences against her persecutors. As I will present below, things happened differently, which, however, may not mean a mental change of the emperor, but simply an attempt to lull the senators and political forces to sleep until they strengthen their position in the office. It abolished the hated and abused law “on the image of majesty”. Censorship, instead of prosecuting forbidden works, found them and published them in public. He rehabilitated those sentenced by the Tiberius administration. He gave the confiscated property. He restored the right to elect a magistrate to the centurial committees, which he definitely did to the senate. He also paid outstanding and current financial obligations to the soldiers and the people of Rome. He renewed the custom of the annual reporting of the financial status tiones imperii. As we can see the enlightened decisions themselves, which unfortunately were followed by a mysterious disease and a radical change. Below I am going to present popular facts from Caligula’s life, wondering whether he was actually insane or whether he fell victim to distortion.

One of the first moves was the slaying of his political ally, Macron, and the underage, still the main rival to the throne, Tiberius Gemellus. Of course, at first glance, these actions are vile through and through, but let’s think about it. In the realities of the time, after a six-month reign and consolidation of one’s power, is an attempt to strengthen it an illogical symptom? Of course, killing a young boy is a cruel act and in today’s moral realities unacceptable. In the Rome of the first century, however, it is a thoroughly logical operation. As for Macron, Caligula saw exactly what Sejanus was doing in the court of Tiberius, so maybe he was afraid, I think, moreover, that it was right that Makron would do likewise and, anticipating the mishaps, made a preemptive move. Is it a symptom of a mental illness? In my opinion, no. The emperor simply dropped his mask and began to take revenge on his family’s torturers. It cannot be said that this is a glorious behaviour, but given the realities of the epoch and the situation, I will risk saying that it is normal. Of course, such a procedure could not go without a senate response. There was a conspiracy. The main actors were the army commander Getulik and Marcus Emilius Lepidus, former husband of Drusilla. And here the things that followed can be interpreted in two ways. Reading literally Suetonius we will learn about other illogical, harmful and ridiculous facts9. Auguet interprets them in a completely different way, however. He claims that going personally in a hurry to the place of the rebellion was the most logical matter. Upon arrival, he immediately lost the leaders of the rebellion, and purged the army, replacing the commanders even of those who were to get retirement rights soon – it is hard to deny this argumentation. The commander was Galba, who attached great importance to discipline, and introduced discipline in the army, which Getulik abandoned. Suetonius now describes the antics of Caligula related to a game of “cat and mouse”, in which the army led by him took part. In turn Auguet interprets it as military maneuvers10. Logic cannot be denied to this argument as well.

It is also worth adding that the two sisters of Caligula were involved in the plot. As proof of this, their private correspondence was obtained and made public. They were sentenced to exile and their property confiscated. Does the fact that the toil and the evidence were made public indicate the behaviour of a foolish, sick, bloodthirsty beast? There are reasonable doubts about this.

Another issue is the invasion of Britain planned by Caligula, which was to follow the suppression of the conspiracy in the legions of Germania. It is often given as one more example of unsynchronized, ill-considered actions taken in a frenzy. Undoubtedly, preparations for the invasion have taken place. This is evidenced by the fact that shortly after Caligula’s attempt, such an invasion was made by Claudius, probably drawing some funds and some preparations from Caligula’s work. Suetonius writes about the whole affair very laconically in a few sentences. It’s even hard to conclude that the emperor is planning an invasion. According to Auguet, the matter is more complex. He claims that the entire campaign was prepared and at the last moment the soldiers refused to board the prepared ships, fearing fighting in a foreign land11. The fact that the invasion was prepared also indirectly belies the thesis that Caligula squandered the entire state treasury that Tiberius had left behind. But returning to the invasion, according to Auguet, Caligula, in his helplessness, ordered his troops to collect shells on the beach. According to Suetonius, this is another prank, and according to Auguet, it is a consequence of the situation in which he found himself. Considering the military history of Rome and the discipline of the legions for which they were famous, it is difficult to imagine such far-reaching insubordination. Therefore, in my opinion, if there were any factors preventing the invasion, they had to be other than the open revolt of soldiers. On the other hand, even Julius Gaius Caesar, looking at it, had trouble with his soldiers. As we read in About the Gallic War12, his legions also did not want to go on an expedition against the Germans. In this case, however, Caesar, who had disproportionately greater authority, personality and experience, dealt easily with this fact. He said that since the soldiers were afraid to go alone, then he would go alone at the head of the 10th legion, in which he fully trusted. So maybe the order to collect seashells on the beach was an attempt, if probably ineffective, to mobilize soldiers. Well, the fact that Caligula could not compare with his illustrious ancestor is incontestable.

Personally, I would be inclined to the thesis that if there were in fact any factors preventing the invasion, they had to be other than the open revolt of soldiers. Perhaps it was a lack of authority, an ineptitude, a desire for Caligula’s apparent and easy success so that he could have a triumph, or an ovation.

Another issue in Caligula’s life was religion. He elevated his deceased sister, whom he respected very much, to divine dignity. Of course, he also saw himself in the pantheon of God. The conflict between Caligula and the Jews is characteristic here. On the wave of his divinity, he decided to place his statue in the Temple of Jerusalem. And here this issue is highlighted as a manifestation of Caligula’s unbalance, and it was rather about Caligula’s ignorance of the Jewish religion, and also the fact that he did not foresee how much conflict it could cause. Auguet writes that after hearing the Jewish delegation, the emperor withdraws his decision13. Józef Flavius presents the matter differently. He says that Caligula did not change his mind, but the legate of Syria Publius Petronius, after hearing the Jewish delegation that told him that all Jews would die sooner than allow the statue to be brought into their temple, tried to persuade the emperor to change his mind. The one in the letter for this hesitation ordered him to commit suicide, but fate wanted Caligula to be murdered soon after, and the letter he sent to Petronius arrived later than the information that the emperor was dead. Therefore, the statue was not placed in the temple and Petronius could still enjoy life14. The case is also described by Philo of Alexandria in his letter, giving as an example the riots that resulted from the famous case of shields15, which would have resulted from an act that was disproportionately worse in the eyes of the Jews. Would an unstable psychopath who does nothing but himself and his divinity change his mind under the influence of someone else’s advice? The very idea of putting your likeness in the temple is not surprising at the time, so many did before Caligula and after him. He did not have to have, and probably did not, know-how seriously Jews treat their religion. So only after gaining knowledge on this subject, he made a decision to cancel the previous order. Personally, I am in favour of the sentence presented by Auguet.

Most of the studies accuse Caligula of ruining the state treasury and administrative anarchy. However, after his four-year rule, the successor could easily pay army bonuses and other state obligations, and in CE 43 he undertook an invasion of Britain, which was quite successful. Maybe in fact inheriting a full treasury from Tiberius avoided the alleged total ruin of the state’s finances, but in my opinion, the assessment of Caligula in this matter should at least be softened.

As far as administrative policy is concerned, even during his reign, although in fact very briefly, it did not have any apparent disruptive effects. The empire was quiet.

Finally, another plot was successful on January 24, 41; Cassius Chaerea murdered Caligula. At least two passages from The History of the Ancient Israel of Josephus Flavius are puzzling. The first, in which he bluntly writes that Caligula’s death does not please the people gathered in the theatre:

But when the rumor that Caius was slain reached the theater, they were astonished at it, and could not believe it; even some that entertained his destruction with great pleasure, and were more desirous of its happening than almost any other faction that could come to them, were under such a fear, that they could not believe it.

– Josephus Flavius , Jewish Antiquities, XIX.I.16

The second, where he describes how, after death, the crowd eagerly seeks and wants to punish the killer by gathering in the Forum, as opposed to the Senate:

Now the senate, during this interval, had met, and the people also assembled together in the accustomed form, and were both employed in searching after the murderers of Caius.

– Josephus Flavius , Jewish Antiquities, XIX.I.20

It is true that after the first fragment, he immediately tries to explain the fact that he was popular only among soldiers, slaves and, worse, women, but in the second case he does not make such allusions, and it is known that only Roman citizens had any vote at the assembly, which immediately eliminates women and slaves. Seen from the sideline and in retrospect, it seems obvious that Caligula had a human backing and was not widely recognized as the harmful deviant of the mentally ill portrayed him.

Details of Caligula’s reign, as found in Suetonius, remain to be assessed. In addition to the facts described above, you can find descriptions of blood-thinning veins. Ranging from accusations of incest, ubiquitous sexual excesses, including rape of wives of invited aristocrats to the murder of his rival to the throne and his recent political allies, as well as condemning people for pleasure, humiliating senators, sophisticated threats that become a tool of psychological torture. until you try to elevate your favourite horse to the rank of consul. Undoubtedly, Suetonius judges the emperor most severely. His work, or rather it’s the part devoted to Gaius Iulius Caesar Germanicus, is divided into three parts. The first tells about Germanicus, Caligula’s father, the second about the period between the death of Tiberius and a mysterious disease, after which the emperor’s behaviour changes drastically. The third part is a description of Caligula’s reign after the transformation caused by disease. The description of the emperor’s father is panegyric, his advantages and achievements in various fields are mentioned. First of all, his loyalty to the legitimate power of Tiberius is emphasized16, one gets the impression that his image is created as a later contrast to the actions of his son. The second part relates to Caligula’s reign before his illness. And here Suetonius describes a series of good things with which the new ruler began his reign. Then, after such an introduction, the very horrible crimes and infamy committed by Caligula are mentioned in one breath. In addition to those described above, about which I have already presented opinions and my opinion, I will also deal with those that are quoted only by Suetonius himself.

The matter of appointing a horse to the consul. Suetonius himself uses the phrase “supposedly”17, which should make us wonder about the authenticity of this statement. Personally, I think that it might be very likely that Caligula wanted to additionally humiliate the senate and aristocracy, which he never forgave for the persecution of his family.

It is also worth mentioning here how the group that “saved the Roman state from the monster” dealt with the wife and daughter of Caligula. Well, they were immediately killed without trial by the conspirators, the little daughter, as Josephus Flavius writes, was thrown against the wall.

Taking into account all the arguments presented above, deciding what really was, is extremely difficult. I think that the presented persecution can, however, be explained by the execution of revenge on senators and people who took part in the conspiracy prepared against Caligula and his family. It cannot be ruled out that in the “heat of the fight”, an innocent person was often hit or the punishment was disproportionate to the deeds, but unfortunately such are the realities of the world in which we live. Reading Suetonius’s account, I personally get the impression that he is extremely biased. Analyzing the facts from a different angle and comparing them with other source sources, I think that the assessment of Gaius Iulius Caesar Germanicus should be less harsh. Especially the descriptions of death presented by Josephus testify that in the eyes of the people he was not as bad as in the sense of senatorial historiography, which is, however, completely normal. Josephus, Flavius, undoubtedly did not respect Caligula, given the scandal involving the placement of the statue in the Temple of Jerusalem, considering that he was a practising Jew from a priestly family. Taking into account the above, I think that the image of Caligula should be revised. Taking into account the arguments presented above, I am inclined to Auguet’s version, according to which most of Caligula’s actions can be explained not by mental illness or madness, but by the need to act in a specific situation.