Chapters

The Roman villa in Eigeltingen, Germany, is one of approximately 3,500 Roman farms in what is today the Land of Baden-Württemberg. The area on which the farm was located is looked after by the Association for the Support of the Roman Farm in Eigeltingen.

Short history

It is the year 80 CE. In Rome, the Emperor Titus Flavius opens the Colosseum with great festivities. 950 kilometers or some 635 Roman miles north of the Eternal City, a Roman legionary – we would never meet him again – after twenty years of faithful service, receives a retirement land on the border of Upper Germania and Raetia. This form of remuneration was common at that time. Perhaps, after a long journey with the whole family and servants, he will reach this place from which, in clear weather, he can see the Alps, and behind them somewhere Rome, where panem et circenses are taking place: hundreds of gladiators fight and the crowd howls delight, eating free bread and washing it down with thin vinum. From this new place of settlement, the day of march will take him to Lacus Venetus, today called Lake Constance, on which at that time was sailing a small Roman fleet stationed in Brigantum (today’s Bregenz in Austria), or in Felix Arbon (today’s Arbon in Switzerland). It will take him a day to walk to Area Flaviae (today’s Rottweil – the oldest city of Baden-Wuerttemberg) – a large city at that time, where he will be able to buy glassware, pots from Galia or wine from Dalmatia. He will sell his farm products – mainly cereals and vegetables as well as pig meat – a few miles away in Vicus (today’s Orsingen), where 1800 years later a local boy would find a beautifully preserved statue of Jupiter at a furniture shop construction site.

Let’s go back to our retired legionary, who started a new life by building a solid villa rustica (46 x 32 m), a two-story barn – or rather a farm building (16 x 20 x 15 m) and many auxiliary buildings (including a bathhouse). Stone for construction is provided by the copper quarry. His farm will be small: barely eight hectares of fields in slightly undulating terrain. Two other farms are in sight, and almost 3,500 of them would be discovered within the boundaries of today’s federal state of Baden-Wuerttemberg. What our legionary builds will live on for the next eight generations, until in the dramatic year of 260 CE when his last descendants fleeing the Alemans leave these areas to avoid being murdered. The wild Germanic hordes will build their wooden huts inside Roman buildings and will never turn on the hypocaust – floor heating or hot water in the baths. They will bring a cultural and civilization collapse for hundreds of years. Sitting at his old age in the atrium of his villa rustica, our legionary does not know that in the age of smartphones his villa rustica will be covered with earth, because of lack of money to bring it back to life. The currency of the Empire: the denarius will be replaced by the currency of a certain union: the euro. Our legionary has respect for the forests; not far from here, the silva nigra, the so-called Schwarzwald (Black Forest), begins. Before his death, he set up a votive stone for Silvan, the god of the forest. Read the inscription: IN H (ONOREM) D (OMUS) D (IVINAE) DEO SILVANO CLE ……… EX V (OTO) S (OLVIT) L (IBENS) L (AETUS) M (ERITO (in honor of the house of the forest god) he was pleased with prayer and protected). A coin would be found next to the votive stone and will become a symbol of the place: the dupondius of Emperor Marcus Aurelius from the second century.

Association

Twenty years ago there was a group of enthusiasts. It is such an almost mystical process. It is not known how and from where you suddenly develop a real delight and loving interest for the past centuries. You “light up” – hence the heat. (Professor Niwiński once told me at a congress of Egyptologists in Florence that it is inhaled from the air like a virus and is not curable at all). They began to discover the past of our legionary and his offspring. The location of the ruins was known from earlier 19th-century research. They found a kind-hearted county archaeologist, founded an association called: Förderverein Römischer Gutshof in Eigeltingen, which translates into the English language: the Patron Association for the Roman Farm in Eigeltingen.

Please visit the website: www.eigeltingia.de, which I manage rather amateurishly. Unfortunately it is in German. However, you can guess a lot. Quite a few everyday people from the village or Eigeltingen contracted this bacillus: among them a teacher, a farmer, a bank employee, a communal worker, a pensioner, a social worker … They managed to lift the walls of the farm building up to a height of 1.4 meters, lay paths for visitors, put up five informational panels with explanations. Unfortunately, the remains of the villa rustica had to be covered with earth for protection and left for future generations. To rebuild the walls of the farm building, 105 tons of stone were needed, which we were looking for all over Europe, to match the original’s structure and color. The Hungarian quarry was flooded with floodwater just before delivery so we had to look elsewhere. The whole thing was finished solely with voluntary work. People have dedicated dozens of hours and their own days off. Financial support was provided by donations; subsidies from monument protection offices were rather symbolic. Today you can walk around this place or sit down and dive into the Ancient Roman past. It is a tourist attraction. The opening of the ruins was a great festival for the entire region. Faithfully following Roman rituals, we sacrificed a replica of a votive stone. I admire how eagerly the members of the association gather to mow the grass, repair and clean the paths, check or fix something, etc. They organize trips and lectures. Yes, Rome invokes by chance. Even after almost two thousand years. But that’s another story.

A few words about Roman agriculture in the I – III century north of the Alps

Agriculture in Roman provinces was used mainly to supply troops. It was their duty and their sense of existence. For this purpose, a piece of land was often leased to veterans who, after completing military service, were honorably released (and only then could they officially get married). The location was chosen very carefully: it had to be a healthy and fertile place, a spring or a clean stream was needed near the farm; and the terrain should be slightly sloped so that the areas are a bit drier or wetter – of course in the immediate vicinity of the Villa. For this purpose, specialized advisers, the so-called Clairvoyants were used. They checked the soil, water, health of the local population and the flight of birds and even the guts of native wild animals to avoid the area’s negative impact on agriculture.

The basic food of the legionary (and the entire population) was grain. It was eaten as bread or porridge and used to feed animals. Straw was produced as a by-product, which, like hay, was urgently needed in the stables. In the areas north of the Alps, mainly spelt and barley were grown, as well as oat and, in good places, wheat. Sometimes rye and millet also grew, depending on the region of the Roman Empire from which the court ruler came – and what he himself learned and valued in his youth. The beans were dried (if necessary) and then stored in large buildings. Storage pests were a problem. Currently, it is estimated that even a third of the yield was unusable. The vegetables differed a bit from today’s vegetables, not in the way they were grown (of course only outside…), but in their selection. The varieties were richer than today, we would be happy if we could have so many regional varieties. High-yielders were lacking, and the “Americans” (tomatoes, potatoes, peppers, corn, and string beans) were not yet known, so native, Mediterranean and Asian crops were grown.

The climate favored the cultivation of carrots, turnips and cabbage (the Romans only got to know it after crossing the Alps), as were the onions, garlic, leeks and asparagus they brought with them. Legumes, such as peas and beans, were important for the supply of protein. Many native fruits have been used to provide vitamins – even if the “vitamin” component was not yet known – but the health value of the fruit was known. Apples, pears, cherries and the widespread wild fruit were already used by the Celts. The Romans brought plums from the Middle East with them – and peaches were tasted every now and then, with varying degrees of success depending on the location. It was the same with wine. The local vines were too tart for many Romans; they were used mainly as table grapes. It was preferred to drink sweeter wines from the south, a Mediterranean area with great locations in today’s Italy, France and Greece. Villa Rustica’s herb garden was as well stocked as it is today – most of the herbs in our kitchen come from the Mediterranean. However, the products were not only intended for personal consumption.

Everything that could not be cultivated in our climate had to be imported – no Roman wanted to do without olives, especially oil was transported over long distances, as well as lentils, dried figs and spices. Oxen and donkeys (or mules) were kept as draught and transport animals, and horses bred for riders in legions. The horses were a bit smaller than today’s breeds – Norwegian horses are similar to those of that time. It should not be forgotten that, on average, Roman soldiers were slightly smaller than today’s inhabitants. Meat was very popular among the Romans and was initially supplied by pigs, sheep and goats, the latter giving milk for the production of cheese (milk was hardly drunk), as well as wool and leather. The forest was cut down to keep homes warm. There remained free areas that were only suitable as pastures. Therefore, cattle farming became more and more popular – and the eating habits of the Romans had to change. Meat cattle, short-horned breeds (also slightly smaller than today) appeared to be quite well adapted to the climatic conditions north of the Alps. Meat (especially veal), milk for cheese and the desired skin were provided. The addition of concentrated feed was still in its infancy. Think of poultry on such a farm as “loud and tasty”. The farm was inhabited by geese, ducks, chickens and pigeons. The bees were certainly useful, because honey was the only real sweetener apart from concentrated fruit or wine juice. The indigenous Germanic and Celtic peoples were already active in beekeeping – and thanks to honey, trade with the Romans flourished.

Since the army had to be looked after, large amounts of grain could hardly be mowed with a scythe and threshing by hand, so real “machines”, or at least devices powered by draught animals, were used. Good examples are donkey mills, a threshing roller with a man as “ballast” and, of course, a “lawn mower”. The plows of that time did not overturn the ground like today’s equipment, but were already reinforced with iron and had a wheel frame – these are the practical ancestors of modern plows. Heavy work, such as pulling carts, was done almost exclusively by oxen. Although they were slower than horses, they were much more enduring and stronger.

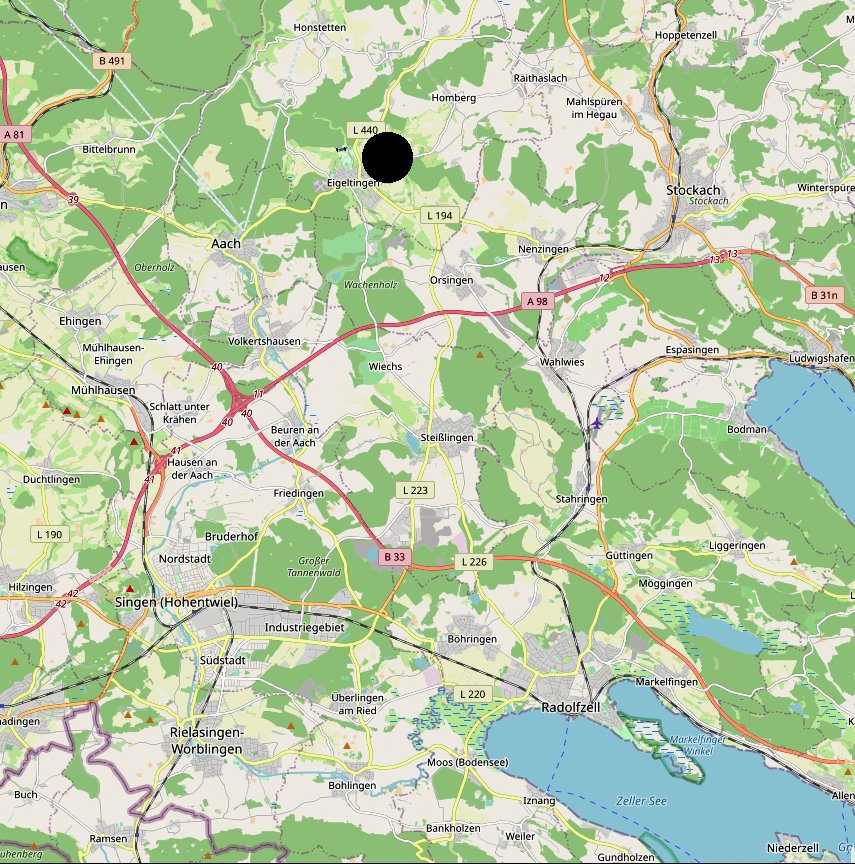

- Roman villa in Eigeltingen on the map

- Visualization of the farm building in Eigeltingen

- Votive stone and building in Eigeltingen

- General view of the farm building in Eigeltingen

- Visualization of the villa rustica in Eigeltingen