Chapters

In addition to gladiatorial fights, the Romans also loved horse racing. The fans were divided into specific factions (factiones), depending on the colours. In ancient Rome, four fan clubs were classically distinguished: Red (russata), Green (prasina), White (albata) and Blue (veneta). In the times of Domitian, two additional teams were introduced: Purple and Gold; but soon after his death in 96 CE, they disappeared. Certainly, the most popular factions were the Blues and Greens – supported by the Emperor’s entourage – as evidenced by the small number of sources regarding Red and White.

But where exactly did these colours represent the teams? In the third century CE, Tertullian mentioned that the Reds were consecrated to Mars, the White Marshmallow, the Greens to Mother Earth or spring, and the Blue to sky and sea or autumn1.

As a curiosity, it is worth mentioning that the admirer of green was emperor Caligula, who spent hours sitting in their stables. Due to the colour of the carriage drivers’ tunes, parties were formed among the audience, whose members often behaved similarly to modern football fans. The viewer who thought that the race should be repeated got up and waved his gown or tunic – when the majority did, the race was interrupted and repeated. Importantly, each team had a maximum of three teams for each race.

The best drivers were great stars in Rome. They have often won a great fortune and worship of Roman women. Most of the coachmen were recruited from slaves. It happened, however, that some impoverished citizens decided on this path to gain wealth and fame. During the race, in order not to let the reins go, they tied them up (and that’s why they always wore knives so that they could cut the reins in the event of an accident – which did not always work).

During the races, there was often cooperation between individual teams to push one of the coachmen onto a spin. Interestingly, in Rome, the exchange of players was also popular, as players now move to other clubs.

The carriage took place in a standing position. The coachmen wore a tunic in a colour matching the colours of the party they represented. The arena of Circus Maximus had its great heroes. Gaius Appuleius Diocles won in 1462, and in 1437 races he came in second place.

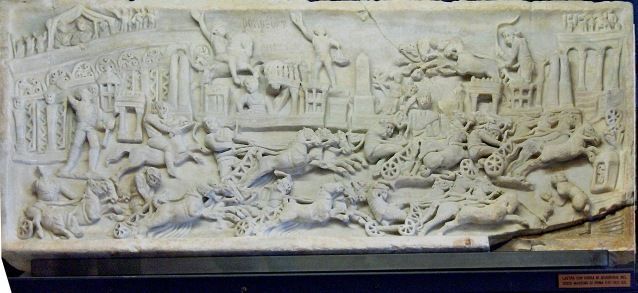

The chariot (currus) was built for maximum speed and the weight was low. The chariots were drawn to two (biga) or four horses (quadriga), but there were also teams with more horses. The quadriga was driven from a standing position and was used mainly for racing and as a car serving during triumphal marches (currus triumphalis) during various ceremonies. Woźnica was called auriga, and the best horse was funalis.

The normal distance was 7 laps, which in the Great Circus gave a distance of 4000 meters. However, the number of laps was changed between 5 and 14 laps.

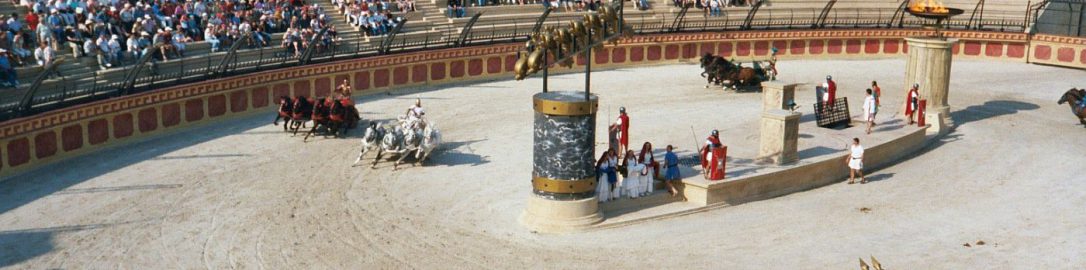

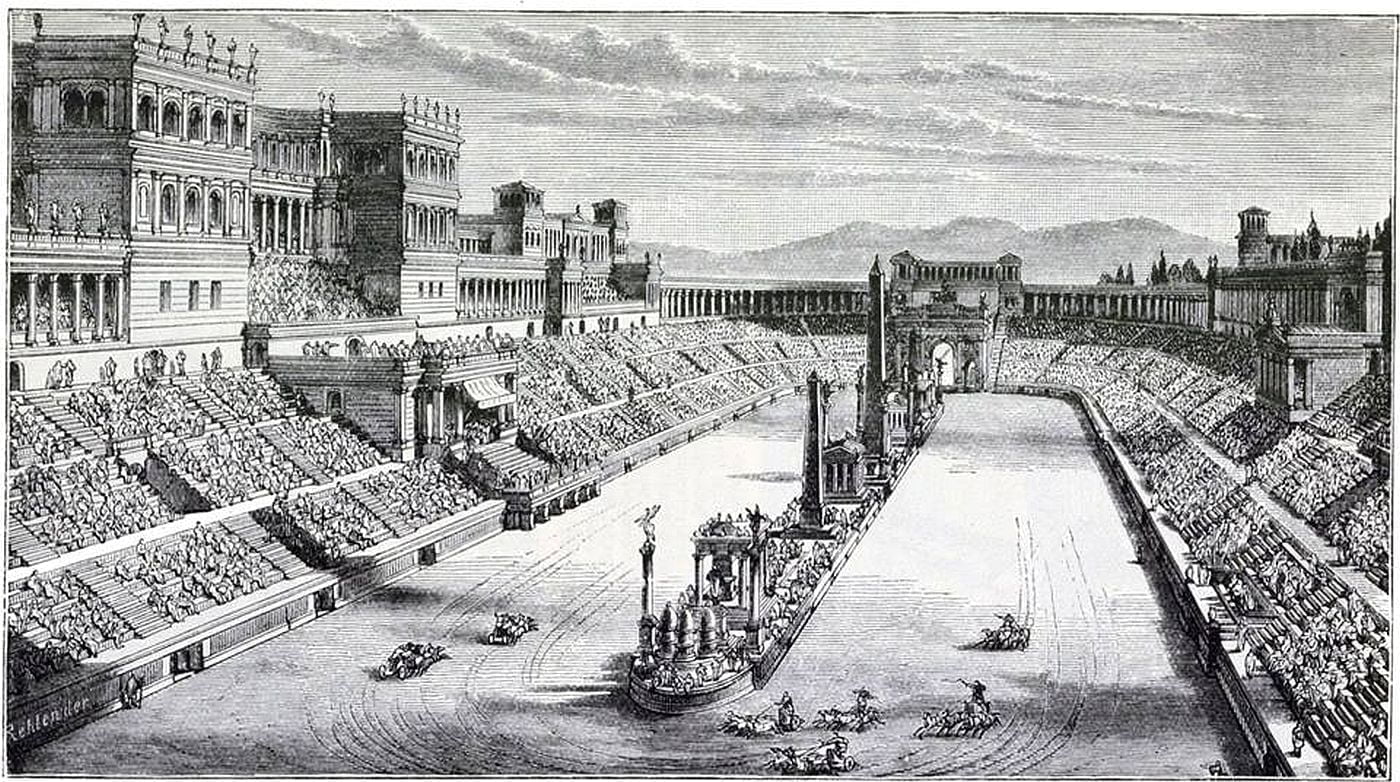

Chariot races took place in a building called circus. The Roman circus resembled a Greek hippodrome. It consisted of an audience and an arena. The latter was very elongated. One of the two short sides had a semicircular shape, and the other had an arch whose chord ran diagonally to the long sides. In the middle of this arch was the main entrance gate, and on both sides of it rose six rooms, so-called carceres for racing cars.

From the side of the arena, they were closed with decorative bars that had devices allowing them to be opened simultaneously with a pull of a rope. Above the coach house, there was a box for the racing chairman. This part of the building, called oppidum, was flanked by two towers. The special slope of the oppidum in relation to the long sides was intended to align the length of the route of all cars. Opposite the entrance gate, on the other, shorter side of the circus, was the triumphal gate (porta triumphalis). From this gate to the oppidum towers, rows of seats arranged amphitheatrically on both sides of the arena. Like in the theatre, they were divided by vertical passages. The outer wall of the circus was arcaded portico. Every third intercolumn was the entrance to the circus. The others housed stalls, small shops or alcoves for rest.

In the middle of the arena covered with a layer of sand, parallel to its long sides, there was a foundation called spina, around which racing cars circled. Both ends of the spins, treated as the finish, were decorated with three conical poles. The finish closer to the triumphal gate was called the first because the wagons first passed it. The finish next to the oppidum, at which the race began, was considered the second. Various ornaments hung on the spin, such as statues, obelisks, shrines and two porticos. One of them was decorated with seven eggs at the top, the other with seven dolphins. After each lap of the spins through the carts, one egg and one dolphin were lowered to help viewers orientate.

The last quadriga races took place in Rome in 549 CE.

Heroes on arenas

Roman inscriptions allow us to meet many heroes of the Roman Games. One of them was a certain Marcus Aurelius Mollicius, a coachman born in Rome who lived barely 20 years.

The inscription mentions that Marcus has won chariot races 125 times during his lifetime, including 89 for the Red team, 24 for the Green, 5 for the Blue and 7 for the White. In addition, he won the 40,000 sestertii award twice.

His brother – Marcus Aurelius Polyneices – was an even better driver. He won together in 739 races, where 655 in Red, 55 for Green, 12 for blue and 17 for White. He took the team three times with six horses, eight times with eight and nine times with ten. He lived to 29 years old.

Based on the preserved inscriptions, the researchers calculated that the average age of the coachman participating in the chariot races in ancient Rome was 22 years. Participation in races made it easy to gain fame and money, but at the cost of a short life.