The ancient Romans used to say: Nihil agendo homines male agere discunt, meaning: “men, by doing nothing, learn to do ill”. For the Romans, descendants of farmers and soldiers, work (labor) was as important as piety (pietas) or destiny (fatum). These concepts formed the backbone of Roman consciousness and identity. They were so important that at a time when manual labour aroused only reluctance and repulsion in the Romans, one of the most outstanding Roman poets, Virgil, wrote a treatise on farm work entitled Georgicon libri IV (The four books of the Georgics).

This work did not help the poet to convince his sophisticated and worldly friends to take up the plow; that wasn’t the point either; Virgil, referring to a wider audience, tried to reinforce in them the conviction that hard work is conducive to moral development and happiness, builds man’s dignitas – his dignity. This talented poet knew how to write light and ephemeral works, and yet he assumed the role of an artist operating in the current of political propaganda. Emperor Octavian Augustus saw him in this role. Besides, they weren’t the only ones who claimed that work was the way to a new, reborn Rome, similar to the ideal community of bees. Perhaps it is worth noting that in the times of great geographical discoveries, the epics of Homer, especially the Odyssey, were extremely popular throughout Europe, while in the Commonwealth the Georgics were still eagerly used. Labor (work, toil, toil) is a rather general term. All forms of public and political activity, commercial and monetary interests, obligations to friends and lawsuits were quite often referred to by the word negotium.

The nature and scope of negotium were conditioned by one’s place in Roman society. However, some activities were the same for all citizens. The Roman, who was also the head of the family, cared for the whole family: his attention was occupied by economic matters, and religious and family duties. He made offerings, settled disputes, and received clients. He was involved in public life: he sought admission to priestly colleges or societies; as long as the Romans had an army composed of citizens and not professional soldiers, he was called to arms; deciding to embark on a political career, he thought about ways to run a successful campaign; held offices; discharging his civic duties, he participated in elections. Holding office was regarded as an honour, and it was not without reason that climbing the ranks of an official career was referred to as cursus honorum; many Romans considered this form of civic activity as a service to the state. It is also understandable that Roman officials came more often from wealthy than poor families: running a political campaign or seeking popularity among voters required considerable financial outlays.

The nature and quality of education in ancient Rome – among many other factors – influenced the course of a political career. Little Romans first learned to read, write and count, then they got to know the literature. Those who were not prepared for public duties did not receive further education. They were not sent to schools run by excellent Greek rhetoricians. The art of speaking, the art of persuasion was the basis of success in politics and in court. It is worth remembering that the Romans willingly settled disputes in court. One of the most famous Romans, Cato the Elder (the same one who, stubbornly seeking to resume the war with Carthage, ended his speeches in the Senate with: Ceterum censeo Carthaginem esse delendam, meaning: “Besides, I believe that Carthage must be destroyed”) has spoken in court in his own defence more than forty times. The Roman statesman, orator and writer, Cicero (104 – 43 BCE) was familiar with about one hundred and fifty of his political and judicial speeches. For those who wanted to appear on the political scene, oratorical talent was indispensable.

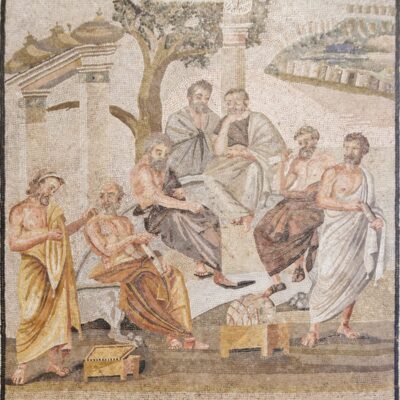

Time free from these activities and spent on all forms of intellectual activity, literary work and its fruits is otium. This term was used to describe all non-public and political activities, meditation, discussion, reading, literary creation, studies, time spent with friends and family, physical activity and leisure. Otium is supposed to give respite to a tired man. There was a popular saying: “Rest after work” (Otium post negotium). There was, of course, a difference between the otium of a simple citizen and the otium of a well-born, educated Roman who cared about his political career.