The younger son of Vespasian did not seem to be a bad ruler. With time, however, he turned into a cruel man, who was decided to be removed from the throne by force. What was the fall of the last emperor from the Flavian dynasty and what signs were to accompany him?

Titus Flavius Domitian was born on October 24, 51 CE as the younger son of Vespasian and Flavia Domitilla. He was the third emperor of the Flavian dynasty. He assumed power in the Empire after the death of his older brother, Titus.

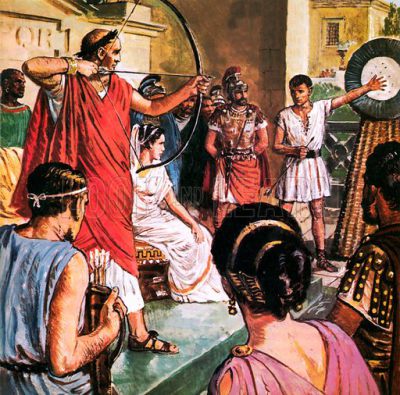

If from among Domitian’s predecessors, he had had to choose his soul mate, the choice would probably be Caligula. The young emperor, who looked pretty good, turned into a cruel paranoid without measure. Domitian, as Suetonius points out, looked good, even in spite of his visible flaws. Vespasian’s younger son was vain, not overworking himself. He rarely rode horses. Even during military campaigns, he preferred to move in a litter. However, he loved archery, in which he became very proficient. Domitian also appreciated as he himself called it, bed-wrestling. Suetonius also mentions a rather peculiar hobby that Flavius found for himself. The emperor was supposed to lock himself in his office and catch flies, which he would later pierce with delight with the stylus. In Lives of the Caesars we can also read about the witty teasing of the famous speaker, Quintus Vibius Crispus. When asked if there was anyone with the emperor, he was said to say that Not even a fly. Domitian was also supposed to abuse his power and position, even by using cruelty, even in his father’s time.

Suetonius argues, however, that at the beginning of his principality, Domitian many times showed generosity, and there was no sign of greed in his behaviour. In Lives of the Caesars we read: he treated all his intimates most generously, and there was nothing which he urged them more frequently, or with greater insistence, than that they should be niggardly in none of their acts. He would not accept inheritances left him by those who had children. He also carefully approached the repair of the Roman judiciary. He curbed the abuse of power by city officials and stigmatized corrupt judges. By imposing a very heavy penalty on false accusers, he also reduced the number of denunciations. He was to say: emperor who does not punish informers hounds them on. All these values, which Domitian was to uphold at the beginning of his reign, however, became the exact opposite of his future deeds.

The third of the Flavian dynasty became cruel, murdering without moderation and for every little thing. On the list of his victims, Suetonius includes, among others Cornelius Scipio Salvidienus Orphytus, Manius Acilius Glabrio, Elius Lamia, Salvius Cocceianus, Salustius Lucullus, and even his cousin, Flavius Clement. Domitian became paranoid and looked for conspirators everywhere. Fearing that someone might be attacking his life, he ordered a shiny stone to be placed on the walls of the porticoes where he was walking. This allowed him to see what was happening behind his back at any time.

It can be said that Domitian brought upon himself a self-fulfilling prophecy. Suetonius writes that the murder of Flavius Clement poured out a cup of bitterness. Moreover, he initiated a series of strange signs that would indicate the imminent end of Domitian. For eight months, there were to be exceptionally numerous storms over Rome. The temple of Jupiter of the Capitol was struck and that of the Flavian family, as well as the Palace and the emperor’s own bedroom. The inscription too on the base of a triumphal statue of his was torn off in a violent tempest and fell upon a neighbouring tomb, Suetonius relates. The emperor was also about to dream that he had lost the protection of the Minerva whose temple he was building. Domitian, however, was most touched by the Askletarion case. The astrologer was accused of proclaiming his visions openly. The emperor was to ask what end the soothsayer would predict for himself. Askletarion replied that the dogs would tear him apart. Flavius decided to outsmart the astrologer. He had him killed and bury immediately so that no dogs would find him. Only that while burying the corpse, another storm broke out, which spread the grave. Then the dogs came running and torn apart the fortune teller’s body.

Domitian, however, sensed his end. And while he used to say that the emperors would not believe reports of the plot until they were murdered, he himself was murdered. The attack was, of course, described by Suetonius. We can read from him that the initiative was shown by a certain Stefanus, who was accused of appropriating money. He was the manager of the court of Flavius Clement’s wife, Domicillian. It simulated an injury to his left arm, most likely a cut, to get Domitian used to the fact that he was wearing a wool dressing still wrapped in bandages. On the day of the murder of the emperor, September 18, 96 CE, he put a dagger under the dressing. It is ironic that he drew the ruler’s attention by informing him of the plot on his life. I will recall Suetonius’s account for the next time. He was reading a paper which the assassin handed him, and stood in a state of amazement. As the wounded prince attempted to resist, he was slain with seven wounds by Clodianus, a subaltern, Maximus, a freedman of Parthenius, Satur, decurion of the chamberlains, and a gladiator from the imperial school. Titus Flavius Domitian fell, wounded by seven thrusts. As if Marcus Junius Brutus, sic semper tyrannis would say. It is worth noting that Domitian’s wife, Domicja Longina, was also to participate in the plot.

The death of Domitian ended the rule of the Flavian house in the Empire. He was succeeded by Nerva, from which began the long and successful rule of Rome for the Antonine Dynasty.