History hides unfathomable layers of secrets and puzzles, the solution of which is sometimes at your fingertips, and other times it is lost in the abyss of oblivion and will never be found again. This is one of the things that attracts me to it – searching, discovering, wandering among possibilities. The knowledge of the ultimate truth is not always the most important thing, sometimes the enigmatic nature stimulates the imagination and allows theories to be made, developing intelligence and motivating for research. This is also the case here – IX Legio Hispana.

The exact date of the legion’s formation is of course unknown. It appears for the first time in the history of Rome’s war with allies 91-88 BCE, where it takes part in the siege of the city of Asculum under the command of a legate Pompey Strabo (father of Pompey the Great). After the end of the allied wars, the legion with units (VI, VII and VIII) is transferred to Spain in 65 BCE, where they watch over the security of Roman provinces and fight the Iberian tribes not fully recognizing the domination of Rome.

Pursuant to the force law granting the governorship of the province of Pre-Alpine Gaul and Illyria with the border on the Rubicon River and Narbonne Gaul Gaius Julius Caesar the legion, along with three others, is once again transferred to Aquileia, where it is rolling battles against the Illyrian tribes. In the meantime, Caesar is planning a preventive attack on the land of the Helvetians (today’s Switzerland), which is a prelude to further actions in Gaul – later called the Gallic Wars. In the meantime, new legions (XI and XII) are formed. All six legions along with auxiliary units take part in the war, including the victorious battle of Bibrakte. Meanwhile, after the victorious campaign, Caesar’s eyes are on the Gauls and the Germanic Suebi. The 11th Legion along with other units takes part in a series of skirmishes, battles, and sieges. The IX troops also secure Caesar’s preparations for the first expedition to Britain in Gesoriakum as well as participated in the battle of the second more successful invasion by fighting with the Britons on the Stour and Thames rivers. Caesar achieved, above all, the main goal of his expedition, which is “to get to know the local people and get information about towns, marinas and access to land”. Appian of Alexandria also mentions the great spoils that Caesar brought from Britain and Gaul, but from the descriptions of the chief himself, in which no “gold” is visible, we can conclude that it was probably about grain, cattle, maybe a supply of tin.

We are now moving into the period of the famous rebellion of Gallic chieftain Vercingetorix, where the IX Legion and other units fight in a losing battle near Gergovia. At this point, it should be mentioned that the IX and X legions, as 2 of the 6 legions taking part in the conquest of the city and the fight against the Gallic army, did not “panic” and with dignity covered the retreat of other units. Again, the Romans and the Gauls meet at Alesia, which goes down in history as the largest siege operation in the history of ancient wars. For the first time, the Roman army built fortifications of such gigantic dimensions. One strip of fortifications was to prevent Vercingetorix from getting out of Alesia, and the other was to protect Caesar’s army from Gallic reinforcements, which soon drew some 80,000 men. The Gauls did not manage to break the siege, and the besieged in Alesia surrendered due to starvation. Caesar won a great victory. According to modern research, Caesar paid for his success with great loss of life among his soldiers.

It is 53 BCE, the Roman legions under the command of Marcus Crassus are defeated by the Parthians at Carrhae this very first triumvirate is falling apart. The conflict between Caesar and Pompey hangs in the balance. Crossing the Rubicon, Caesar begins a civil war at the head of his troops. The IX legion fights again this time against a worthy opponent, the troops of Pompey and the Optimates in the battles of Dyrrachium (where it suffers heavy losses), Farsalos and Thapsus. The legion is disbanded after the final victory, and the veterans are settled in the Picenum area – but not for long.

Caesar’s murder changes everything – civil war breaks out again and IX is reactivated by Wentidius Bassus on the orders of Octavian, heir of Julius Caesar, to defeat Sextus Pompey, who occupied Sicily. Then, after fighting in the Balkans, the 9th Legion fought in the Battle of Actium against Marcus Antony’s army, which brought Octavian to ultimate supremacy. The key war that brought fame to IX was the campaign of Octavian Augustus against the Roman province of Hispania Tarraconensis, the so-called Cantabrian War, where other legions also fought, incl. I Germanica, VI Victrix, X Gemina. The effect of their successful warfare was giving the honourable nickname of the IX legion – “Hispana”.

After this event, the legion was likely part of the imperial army on the border of the Rhine, which was campaigning against the Germanic tribes. After leaving the eastern part of the Rhine (the defeat in the Teutoburg Forest), it found himself in the area of Pannonia. The legion reappears in the annals of history during Emperor Claudius’ invasion of Britain in 43 CE where it wages a successful fight under the command of Aulus Plautius establishing a network of garrisons and, under the command of the new legate Publius Scapulia, defeating the Katuwelauns

Caratacus at the Battle of Caer Caradoc. Since then, the fate of the legion is inextricably linked with Britain.

During the rebellion of Queen Iceni Boudica, the legion is smashed at Camulodunum. Quintus Petlius Cerialis saves the remnants of the troops, which are later replenished with soldiers of Germanic origin.

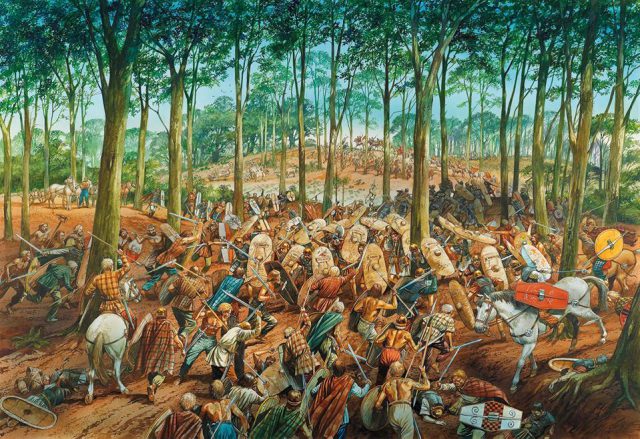

In 71-72 CE it led a fight with the Brigades in order to conquer the northern part of Britain – at the same time a camp was established in Eboracum (today’s York), where it was stationed for a long time. Another glorious page in the history of the legion is the campaign of Julius Agricola and the attempt to conquer Caledonia (today’s Scotland) and the battle

at Mons Graupius where the IX Hispana, the XX Valeria Legion, along with the Batavian auxiliary, break up the Caledonian tribes of Calgacus. Before the events described above, however, the legion was almost annihilated in a nightly attack on the marching camp near Forth. In desperate hand-to-hand combat, the Caledonians entered

the camp, but thanks to the conscious reaction of Agricola, who sent the cavalry on time, which smashed the attackers and, de facto, saved IX from destruction. The last known place of the 9th legion is, of course, the home base in Eboracum, where they participated in the expansion of the wooden camp of 108 CE

At this point, the legion disappears from history, of course, in Britain. There are many theories that suggest what might have happened next.

- IX is completely wrecked somewhere on the frontier of Britain and has not been opened. Of course, there is such a possibility, but previous examples showed us that the legion was replenished or at that time there was not enough human resources to open up. For example, the revolt that broke out in 117 CE, which explains the immediate arrival of the 6th Legion in Eboracum and the construction of the Hadrian’s Wall. The book, Rosemary Sutcliff, “The Ninth Legion,” and the movie of the same title are of course based on this theory. In addition, it is worth mentioning what prompted the writer to present such a theory. At Calleva Atrebatum (now Silchester), in 1866, a gilded damaged Roman eagle is found, mistaken for the Legion’s Aquila. Unfortunately, it was later found that the eagle is part of a statue of Jupiter (it was supposed to hold lightning in its claws).

- Damnatio memoriae (condemnation of memory, eternal oblivion) was of course a punishment in ancient Rome (known earlier in Egypt) for crimes against the broadly understood dignity of the Roman people. So what’s behind it? This punishment consisted in erasing the convict from the memory of posterity, forbidding his descendants to bear his surname and destroying all his images, numbers and documents. What, then, could have caused the legion to be sentenced to such a punishment? Of course, a rebellion, a defeat in a battle or a war that we know nothing about so far. It is worth adding that at least 8 legions suffered such a fate, including three numbered XVII, XVIII and XIX for the defeat in the Teutoburg Forest and one during the battle with the Parthians at Elegy in 161 CE, where the first centurion was to commit suicide and the legion annihilated. The sources, however, say neither the number nor the title of this legion.

- There is also a theory that the legion did not have to be destroyed in battle, but merged with another legion as a result of casualties. If the IX Legion was the weaker element in such a combination, it had to take the title and the number of the stronger IX legion was removed from the army list.

- Archaeological evidence. Several inscriptions confirm the presence of at least one delegated unit from the IX Legion on the Lower Rhine in Noviomagus Batavorum (now Nijmegen), incl. silver-plated bronze pendant, found in the 90s, part of an phalerae (military medal) with the words “LEG HISP IX” on the reverse, an altar of Apollo dating from this period was found in nearby Aquae Granni (Aachen, Germany), erected under oath by Lucius Latinius Macer, who describes himself as primus pilus (chief centurion) and as praefectus castrorum (“camp prefect”, i.e. third commander) IX Hispana. Archaeological evidence also seems to indicate that elements of the IX Legion were present in Noviomagus sometime after CE 104 (when the previous legion, the X Gemina, was transferred to the Danube). Hispana, on the other hand, was probably replaced by the XXX Ulpia Victrix legion not long after 120 CE. The vexillatio Britannica in Nijmegen was also mentioned (it is not known if it was an auxiliary force). In addition, the names of the commanders of the IX legion who could not serve in it before 122 CE are known, e.g. the governor of Arabia 142/143 CE Lucius Lucius Aemilius Karus.

- If we adopt theories that the legion was not destroyed but moved to another station, eg to suppress the Bar-Kochba uprising in Judea. The Romans are known to have suffered heavy losses during the war, the starting date of which fits neatly with the estimated time of IX Hispana’s departure from Nijmegen (CE 120-130). In this scenario, the ninth was sent to Judea to fortify the legions locally but was smashed by Jewish forces and the remnants of the unit disbanded. Moreover, another legion, probably XXII Deiotarian, which was based in Egypt – by a strange coincidence also appears in Judea (but it did not have to fight in it, perhaps XXII Deiotarian is destroyed by Parthians under Elegey), and all information about him also disappears after 120 CE. Possible that both legions had been destroyed by the Jews, but if so, it would have been the greatest Roman military defeat since the Battle of Teutoburg Forest.

Summarizing, the fate of the 9th Hispana Legion will remain the subject of lively debate.