Chapters

In ancient Rome, the simplest method of conveying information or the content of your work was to deliver it – recitation (recitatio), which was certainly based on Greek symposiums (symposium). Seneca the Elder reports that a certain Asinius Pollio, who wrote during the reign of Octavian Augustus (27 BCE – 14 CE), invited guests to read his work1. Pliny the Younger, Martial and Juvenal regret that in their time there was a really big number of people reciting their songs.

The way of writing in ancient Rome

The works were written at:

- wooden plaques covered with wax,

- papyrus (made from papyrus cane)

- or parchment (made from animal skin).

Wooden signs covered with wax

One of the basic ways of writing was to use wax tablets on which you wrote down with a sharp stylus. They were so convenient to use that the writer could erase the wax and reuse the plaque. Such signs were also very popular in Greece and the Middle East. They were commonly used in administration, fiscal and judiciary, and bills and various registers were written on them. They were also used for correspondence (after blurring the wax layer, the return answer was placed on the same plate), as personal notebooks, or in schools – for learning to write and count, and for writing literary works. This is mentioned, among others, by Quintlian2. According to Marcjalis3, such tablets could be made of citrus or ivory wood. After receiving the news from his lover about the cancellation of the meeting, Ovid wrote: “I can do nothing in my anger but pray that old age gnaws you with woodworm and that your white wax may end in an ash heap”4.

In order to erase the notes on the wax, the tablet was heated to about 50°C and the surface was smooth. The writing was done with a tool called stylus which required more force than writing on papyrus or parchment in ink.

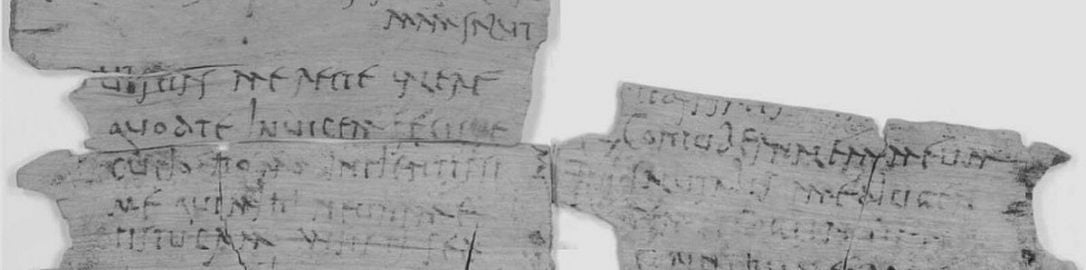

Tablets from Vindolanda

In 1973 an unusual discovery was made in the Roman camp of Vindolanda (England). Water-soaked tablets with Roman notes were taken from the ground. After the conservation works, it turned out that the artefacts are a great source of information about the lives of people who lived in the camp in ancient times. The people writing on the tablets used too much force, and the stylus also left marks on the wood. From the letters, we can read about, inter alia, orders for deliveries of bacon, oysters or honey; a message addressed to the legionary stating that more socks, sandals and underwear had been shipped; or the impressions of the Romans about the Britons.

Among the tablets, we can also find the official invitation of the sister of the camp prefect by his wife to a birthday feast:

Klaudia Sewera greets her Lepidina. Sister, on September 11, on your birthday, I warmly invite you to visit us to treat me with your presence. Give my warm regards to your Cerialis. My Aelius and my little son also greet you. I hope you will be there. Goodbye, sister, my dear little soul, and I hope for the best. To Sulpicja Lepidina, Cerialis’s wife, of Severus.

The notes of the wife of the prefect Aelius – Claudia have thus become the oldest example of the use of written Latin by a woman, which have survived to our times.

Wooden signs are found in various regions of the former Empire: North Africa, South Italy (especially Pompeii and Herculaneum), Switzerland, Britain (Hadrian’s wall), Egypt or the former Dacia.

Papyrus

Few Roman works on papyrus have survived to our times, especially in Latin. This is due to the fact that papyrus was produced in Egypt, and Greek was the more popular literature there. If any Roman material has survived in Latin, most of it was from the late Empire and related to Christianity. In antiquity, papyrus wrote in columns (paginae) that ran perpendicular to the length; the written papyrus was stored as a scroll. It was an effective way to store long materials. Moreover, rolling the papyrus was harmful to me, rather than folding it into smaller pieces.

Interestingly, in 2015, scientists used modified X-rays to try to read preserved, charred papyrus scrolls in the Herculaneum library. This method made it possible to extract individual letters from damaged documents. The scrolls were charred by the heat that fell on the city after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 CE. As it turned out, the library was full of works by Philodemus of Gadara (c. 110 – c. 39 BCE), a Greek poet and philosopher from the Epicurean school, who was the teacher of the poet Virgil.

Scientists have so far found around 1,800 charred and blackened paper rolls from which they tried to read any words. Some of the scrolls could be rolled out, but many are in such bad condition that no mechanical action can be afforded. Ultimately, scientists managed to get to know some of the notes from the two scrolls.

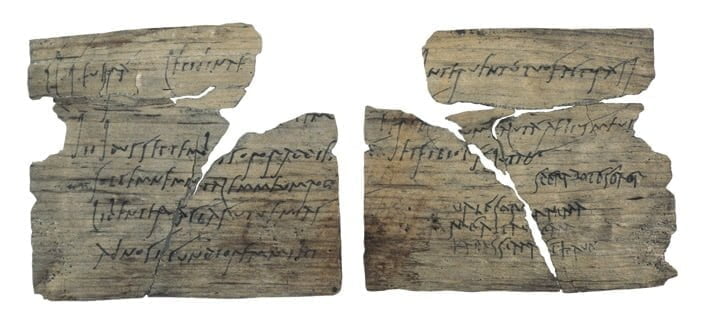

The oldest correspondence in Latin

The oldest correspondence in Latin comes from Egypt. In 30 BCE Egypt became part of the Roman Empire, and thus a provincial difficult to control. In 22 BCE the prefect of Egypt, Publius Petronius, in reaction to the invasions of Upper Egypt, sent a Roman garrison to the south of the country, which settled in Primis (today’s Qasr Ibrim). Soldiers of the vexillationes of the 3rd Augustus Legion served there for one or two years.

During this time, they travelled to the place where their main camp was located (probably Koptos on the Red Sea), and even to remote Alexandria. Koptos was a town of very important strategic importance – on the Nile (middle course of this river) and relatively close to the Red Sea. Earlier, the legionaries camped in Luxor, along the trade route from Asia. The soldiers, being outside the garrison, wrote letters to their companions. Papyrus notes did not constitute any greater value for those days. On the outside of the ancient wall, a substantial collection of papyri has been discovered. The papyri contain Greek and Latin texts. The latter are fewer, but they are the oldest handwritten texts in this language known to science. Most of the papyri are documentaries: the aforementioned private letters addressed to the soldiers of the Qasr Ibrim garrison dominate, there are also lists (supply of goods, legionaries present in the garrison). We also come across the usual letters of legionaries, probably written out of boredom.

One of the letters was written by a soldier – a trumpeter named Kajsios, who left a distant Egyptian post and went to Alexandria (approx. 1,200 km). From the capital, he wrote to a certain Likinios. The letter tells us, among other things, that the reason for the long journey was to bring the mouthpiece to the trumpet.

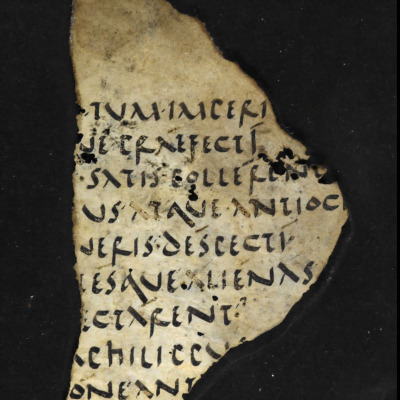

Parchment

With the development of Christianity in the Roman Empire, the papyrus scrolls began to depart, and the parchment or papyrus codes, which were much handier and had the form of current books, turned out to be a revolution. It cannot be ruled out that the Christians deliberately departed from the scrolls, due to the desire to clearly separate the Old Testament from the New, which began to be written in the form of a code. Codes also allowed for better storage and increased the durability of the works. Unfortunately, only some of the ancient works were transcribed into book form, and therefore the enormous achievements of the ancient world were lost. Classical literature was massively rewritten by scribes in the 4th century CE. on vellum, a high-quality, thin layer of leather.

Parchment could also be kept in the form of a notebook – the so-called membranae; Marcjalis claims that it was very handy and convenient to travel5.

Ancient Romans used ink, usually made of rubber and soot, to write on papyrus and parchment. They used red ink to better visualize the titles. The ancients also knew the “likeable” ink. Pliny the Elder mentions the tithymalos plant (known as tithymalos characias), which was referred to as a “milk plant” or “goat’s lettuce”. Writing the inscription with its juice, it is invisible after drying; in order to show the content, it was enough to sprinkle ashes6.

Other ways to save

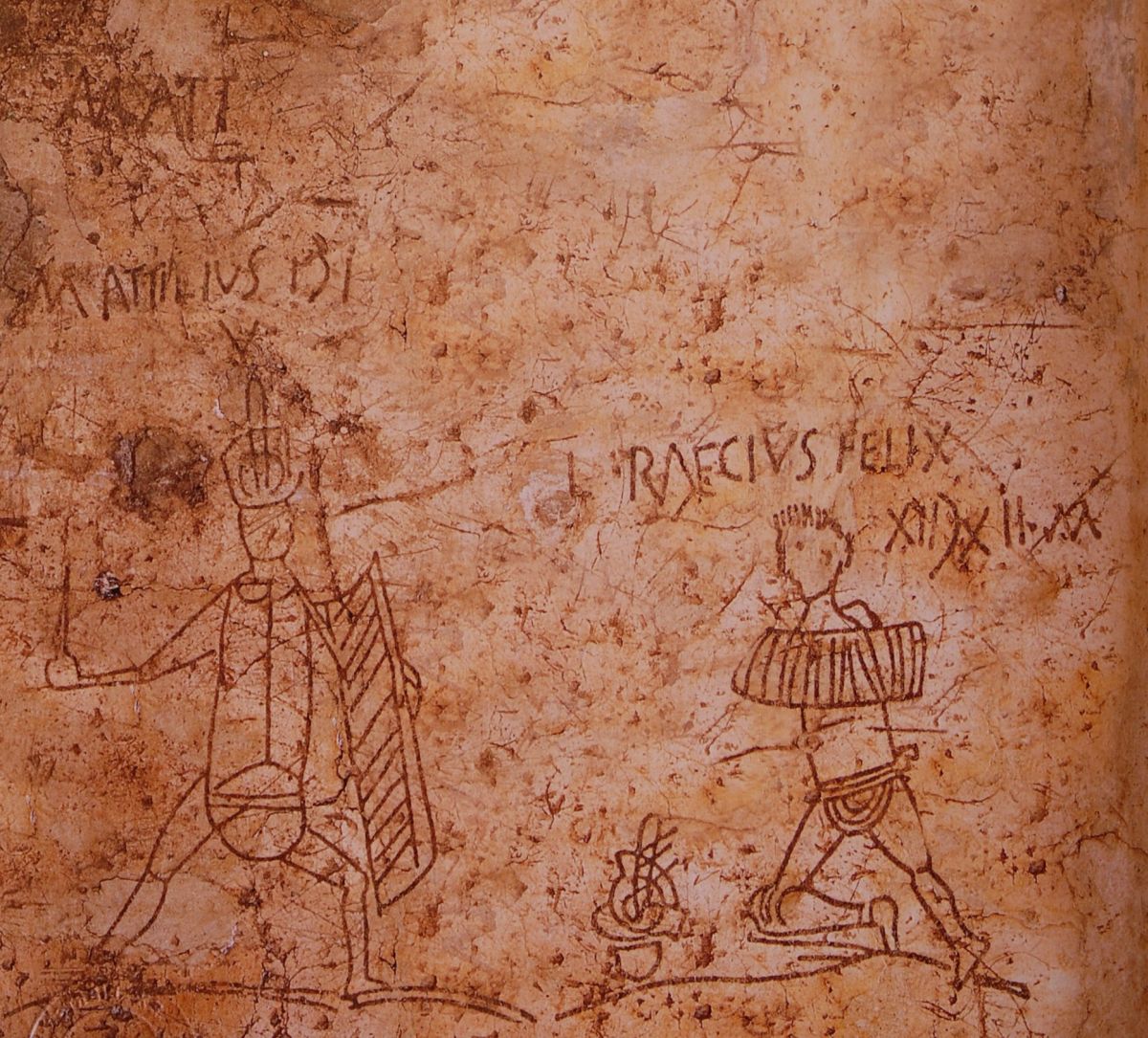

They also wrote on the walls in the form of murals or on fragments of ceramic vessels. These were easy ways to express emotions, create advertisements, or use propaganda.

The Pompeii graffiti below shows the story of Marcus Atillus –gladiator – who defeated Lucius Raecius Felix, winner of 12 matches in a row. It is known that Felix survived the fight despite the defeat and was set free.

Below, is an antique drawing of an Egyptian child on a fragment of a pottery vessel. The object was found at Athribis (Egypt); it is dated to the 1st century BCE – 1st CE In ancient times, the ostracon was used as a cheap writing material.

How was content copied in the ancient world?

In ancient times, making multiple copies of a song was not an easy task. Most often, the work was dictated, and several scribes wrote down words at the same time. Naturally, there was a real chance of a mistake between the dictator and the writer, hence researchers to this day find errors in ancient texts and records. As it turns out, high-quality copyists were worth a lot – as mentioned in Seneca the Younger7 and Horace8 . Before the work was released, publishers used the services of proofreaders (anagnostae), who read the content and reviewed the work for possible errors.

Certainly, there were also re-editions of the works and their subsequent editions. For example, more than one antique edition of Cicero – Academica has survived to our times. We also know that the originally published work of Ovid – Ars Amatoria from 20 BCE in five books – later it was circulated in three books.

Libraries

In ancient Rome, until the 1st century BCE, there was no public library, such as, for example, in Alexandria. The first decision about the need to create a public library, in which numerous classical works will be collected and classified, was made by Julius Caesar, who asked Marcus Varro for help for this purposeCaesar, 44" data-footid="9">9. Finally, the work was completed after Caesar’s death, in 39 BCE, when Asinius Pollio established a public library in Atrium Libertatis, between the Capitol and Quirinal Hill. During his reign, Augustus additionally opened a library in the temple of Apollo and on the Field of Mars in 28 BCE. In Rome alone, in the middle of the 4th century CE, there were already 28 libraries.

There were, of course, private libraries in addition to public libraries. A great surviving example is the Herculaneum collection, discovered in the 18th century, which researchers believe may have belonged to consul Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus. Interestingly, the library has preserved charred papyrus scrolls, which are important research material.

In the 1st century BCE, a large private library in Tusculum could also boast of Lucullus, which was open to the public. The library was a large part of his villa, many of which were certainly war booty:

But what he did in the establishment of a library deserves warm praise. He got togetherº many books, and they were well written, and his use of them was more honourable to him than his acquisition of them. His libraries were thrown open to all, and the cloisters surrounding them, and the study-rooms, were accessible without restriction to the Greeks, who constantly repaired thither as to an hostelry of the Muses, and spent the day with one another, in glad escape from their other occupations.

– Plutarch, Lucullus, 42