The origins of Rome are shrouded in mystery. There are many legends about the rise of Rome. One of them says that the city was founded by the hero of the Trojan war – Aeneas. After capturing and destroying Troy, he was to come to a land called Latium. He died shortly thereafter, which caused prolonged struggles to gain power among his descendants.

Numitor, king of the dynastic city of Alba Longa, was thrown from the throne by the usurper and also his own brother Amulius. The winner gave the daughter of the defeated – Rea Silvia for the service of the goddess Vesta. Soon she gave birth to twins (Romulus and Remus) in a relationship with the god of war Mars. The ruler of Latium – Amulius, learning about the birth of boys, ordered to kill them by throwing into the river Tiber. The mother, not wanting to lose her children, put them in a wicker basket. However, it did not go further with the river current, because it caught on to the branch. The boys were found by a she-wolf, who fed them and gave them to raise the royal shepherd. There is a belief that the wolf may have been the lord of thunder – Zeus. As the boys grew up, the fight broke out between them, as a result of which Romulus killed his brother Remus. Romulus built a city named after his name – Roma – meaning Rome.

The oldest traces of settlement that have been found so far on the Tiber River, dated between 1000 and 800 BCE Rome, probably created in 753 BCE. Until recently this date was almost unanimously questioned by specialists. The Romans themselves did not agree with this. This dating is by Marcus Terentius Varro, a researcher of past history who lived in the 1st century BCE. It gained popularity thanks to the monumental work Titus Livy, who used the date used by Varro, writing his Ab Urbe condita. According to the tradition handed down to us by Livius, Rome founded Romulus on April 21, 753 BCE and became its first king. From this date, the city’s history was calculated – Ab urbe condita or AUC (“since the city was founded”). Almost two thousand years after Livy’s death, however, it gained amazing confirmation in the results of archaeological research conducted at the turn of the 1980s and 1990s along the road leading from the Forum to the Palatine.

An Italian archaeologist, Andrea Carandini, investigating the area, found there were traces of a wall along the Palatine slope around the middle of the 8th century BCE. These studies do not indicate the exact date the city was founded on the Tiber, but they confirm the existence of urban clusters in this place already in this early period. The place was exceptionally well-chosen. It was most comfortable here, looking from the mouth of the river, crossing the Tiber. So it had to lead this way leading to the coastal salinas, a place of obtaining salt, necessary for the Sabine mountain tribes dealing in cattle and sheep breeding. This road also led to the cities of southern Etruria. The Bend of the Tiber just off the island gave a convenient port to which Phoenician and Greek ships with various types of goods could arrive. In other words, it was a dream place for a shopping centre.

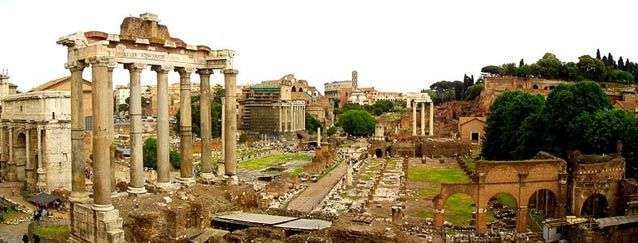

The Palatine settlement after about a hundred years merged with the second village, inhabited by the Sabinów, focused on the slopes of the Quirinal and Capitol. Separating the two communities, the swamp was buried and thus one of the most famous tourist destinations in Rome was created – Forum Romanum.

Rome was built on the seven hills (Septimontium). Seven hills, all located on the eastern side of the Tiber, constitute the heart of the city. They played a very important role in mythology, religion and in the politics of ancient Rome. According to tradition, the city was founded by Romulus in the Palatine (Mons Palatinus).

The seven hills include:

- Aventine (Mons Aventinus);

- Palatine (Mons Palatinus). Its western slope was named Cermalus ;

- Quirinal (Collis Quirinalis). It consists of three peaks: Latiaris, Mucialis and Salutaris ;

- Viminal (Collis Viminalis);

- Celius (Mons Caelius);

- Esquiline (Mons Esquilinus). Consisting of summits: Oppius, Cispius and Fagutal ;

- Capitol (Mons Capitolinus), whose pass called Asylum, divides the northern summit Arx from the southern proper Capitol.

There are also other hills not included in the list of seven hills like Velia, which connects the Palatine with the slopes of Eskwilin. Another pass connecting the Capitol with the Quirinal was opened in the 2nd century CE when the Trajan Forum complex was being built. On the west side of the Tiber are the hills Vatican (Montes Vaticani), Janiculum (Ianiculum) and Pincio (Mons Pincius).

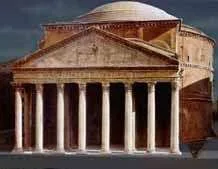

For the first 250 years of its existence, Rome was a monarchy. In the second half of the 6th century BCE under the sceptre of the Tarquinius family, it achieved the position of one of the most powerful monarchies on the Apennine Peninsula. Various cultural influences intersected at the time. An Etruscan culture marked their presence very strongly, but Greek and Phoenician influences are also clearly visible in the art of this period. However, the Latin language and culture have not disappeared; they made Rome separate from other flourishing urban centres in Italy. The city was distinguished by the largest temple in the so-called Etruscan style dedicated to the gods of gods Jupiter, founded in the last years of the monarchy’s existence. Until the end of Rome, it was believed that the basis of its social and political institutions was the work of individual rulers. Some of these institutions have survived to this day, such as the Senate.

During the kingdom, Rome was ruled by seven rulers. They took turns to sit after Romulus: Numa Pompilius, Tullus Hostilius, Ancus Marcius, Tarquinius Priscus, Servius Tullius and Tarquinius Superbus. The monarchy had its peak period of development in the sixth century BCE when it ruled over the western Mediterranean thanks to its alliance with Carthage. At that time, from 616 to 509 BCE, the last three kings of Rome, of Etruscan descent, sat on the Roman throne: Tarquinius Priscus, Servius Tullius and Tarquinius Superbus. Modern historians consider Romulus a legendary figure, but they are inclined to recognize the historicity of the next Roman kings, especially the last three rulers of Etruscan origin.

Kings of Rome with dates of reign | |||

Romulus | Legendary founder and the first king of Rome. He would rule for a long time and then be taken alive to heaven to become the god Quirin. | ||

Numa Pompilius | Second legendary king of Rome. Sabine, a religious legislator, and founder of priest and craft colleges; moderated customs in Rome and enacted numerous laws. | ||

Tullus Hostilius | Third King of Rome. He enjoyed the fame of the great warrior, the conqueror of Alba Long. He built many meetings for the Senate, including Hostilius’s curia. | ||

Ancus Marcius | Fourth King of Rome. Builder of the first bridge on the Tiber, and founder of the port of Ostia; joined the Aventine and Janiculum hills to Rome. | ||

Tarquinius Priscus | The fifth king of Rome, who was of Etruscan origin. During his reign, the construction of Circus Maximus and sewers – Cloaca Maxima began. According to scientists, he is considered the authentic ruler of the Roman monarchy. | ||

Servius Tullius | Sixth King of Rome. So-called builder Servian walls surrounding the city. He was the first to order a general census of Rome and divide society by property classes. In this way, he increased the size of the army and reduced the dominance of patricians. | ||

Tarquinius Superbus | The seventh and last Roman king of Etruscan origin. Finally overthrown by the aristocracy. According to scientists, he is considered the authentic ruler of the Roman monarchy. | ||

The Etruscan civilization had a huge impact on Rome. The Romans borrowed from the Etruscans: the laws of the court procedure, triumphs, the alphabet, the art of building temples, realism in sculpture and painting, and divination. They probably owe the establishment of three organs of power in the kingdom, in the form of a king, curial assemblies and a senate. The end of Etruscan domination can be linked to the general political situation in Italy after losing to the Greeks the naval battle of Cumae in 474 BCE, and the loss of the Campaign for Samnites. Etruscan influence also left its mark on the name of the nation: Romani, Roma (of Sabine origin, and therefore the pre-Greek name is: Quiris, Quirites).

In 509 BCE the inhabitants of Rome, discouraged to a foreign monarchy, overthrew king Tarquinius Superbus and established a republic. The first consuls elected for one year were Lucius Junius Brutus and Tarquinius Colatine. After the fall of the monarchy, Rome gradually declined. It was destroyed by internal disputes as well as wars with the Sabbath mountain tribes of Ekwami and Volsci descending into the valleys.

Roman society was extremely conflicted. It was divided into patricians and plebeians. The Patricians were the privileged, higher social layer that appeared during the republic. They had full political rights (up to a point) and exclusive rights to office. They came from wealthy families. Initially, they were probably descendants of the ancestral aristocracy (a closed number of families – “gentes”), which in the early period of the state (royal and early republic) enjoyed full political rights.

The plebeians, in turn, were free, but (up to a point) they did not have civil rights. They could not include state offices and marriages with sons or daughters of patricians. They dealt with crafts and trade. They also served in the army and had to buy weapons for their money (although after the reform at the end of the second century BCE, it was provided to them by this state). The plebeians could only participate in the people’s assembly. Crops often reigned during this time, so the plebeians fell into debt, which ended in a brutal fate for the slave.

Thus, it is clear that the opposite of the patricians were plebeians who fought to equalize their rights against the privileged aristocracy. They undertook the fight for political equality with patricians. In 367 BCE they gained access to the Roman Senate, and full rights were obtained in 287 BCE, Patricians, being part of the Senate, exercised rule in the republic. From 445 BCE, patrician marriages with plebeian daughters were allowed. The power monopoly usurped by patricians caused a conflict with the plebeians. The struggle for the separation of powers ended at the beginning of the 3rd century BCE when the unstable balance between the two groups was established. Only some sacred functions were permanently assigned to patricians (until 44 BCE).

Internal disputes were mitigated by the introduction in 449 BCE of the “Law of XII tables”, the first Roman codification of customary law. This codification unified Roman society. This is clearly indicated by the results of archaeological research. We have numerous monuments confirming the occurrence in Rome of developed aristocratic culture, drawing examples from Greece, Etruria and Phenicia. In finds from the sixth and first half of the fifth century BCE, there are numerous symposium ceramics, which disappear after this period.

Since the introduction of the “Law of the Twelve Tablets”, Rome has for many years been a primitive culturally-oriented peasant society oriented towards external conquests. In the first half-century after the fall of the monarchy, there was also the establishment of basic republican institutions, which constituted the character of this state for the next four hundred years. Executive, instead of the monarchy, was taken over by two consuls elected for one year. Collegiality and a relatively short period of consulate made it difficult for the individual to seize power. The existence of an advisory body at the consul was also sanctioned, i.e. the Senate. It included heads of the most important families, which played a key role in Roman society. Success in wars with the invasion of the Sabel peoples prompted Rome to strike north.

This conquest was only a prelude to a much more important military achievement, i.e. the victorious war with Veii. Veii was the closest Etruscan neighbour of Rome – a city of similar size, wealth and human resources. Conquering it doubled the territory of Rome. For some time it was not known what to do with such huge prey. Roman warriors looted the movable property of the Vientinines. The problem, however, was land. It took a great mental shock to solve this problem, and this happened after the capture of Rome by the Gauls. Gauls after the dramatic defeat of the Roman army on the Allia River captured the city in 386 BCE. They left it only after receiving the ransom paid by the ally of Rome – Caere. Shortly thereafter, the territories captured by Rome on the Vientiane were divided among Roman men. Thus, Rome became a city without landless citizens for some time. At the same time, the struggle between the old nobleman patrician and the citizens of considerable wealth, but without proper descent, concentrated in a plebeian state opposing the patrician state intensified. It took Rome the next hundred years to subordinate Italy.

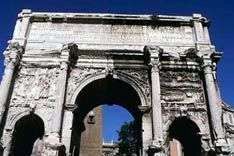

With time, more peoples and states bowed their heads under his yoke. The Romans confiscated a significant portion of the land defeated opponents and formed military colonies in this area. At the same time, they formed military alliances with defeated enemies, for whom the only chance to regain their wealth was often to participate in Roman conquests and take part in subsequent colonization. In this way, a combined army of Romans and their allies grew in strength from year to year. Conquest connected all social strata of the Eternal City. Ordinary citizens got richer and gained land. Aristocracy gained fame, which in the ancestral system, with the underdeveloped monetary economy, determined the social position and prestige surrounding the individual. The victorious war ended in triumph, and a special procession that passed through Rome and ended at Capitoline Hill, was the dream of every aristocrat.

The full rule of Rome over the Apennine Peninsula guaranteed victory over the Samnites in a series of heavy wars waged in the second half of the fourth and the beginning of the third century BCE The climax of this fight was the victory at the Sentinum in 295 BCE over the combined army of Gauls and Samnites. After defeating them, only the Taranto remained on the Romans’ way. The city was called in 280 BCE to help one of the best antiquity leaders Pyrrhus, king of Epirus. He defeated the Romans in two consecutive battles, at Herakleja and Ausculum, but suffered huge losses. Not resolving the war, he transferred military operations to Sicily, acting against Carthage. After returning to Italy, in 275 BCE he suffered a defeat in the clash with the Romans near Benevento and left Tarente alone. The city capitulated in 272 BCE After defeating Taranto, paying homage to Puglia and Messapia in 266 BCE, and capturing the last free Etruscan city Volsinia in 264 BCE, Rome ruled all of Italy up to the northern arch of the Apennines, behind which the Gallic territories began.

To make it easier to control the peninsula, the Romans began building their famous roads. The first was via Appia, whose construction began in 312 BCE. Then the first Roman aqueduct was built. A very characteristic element of Roman culture – gladiator fights – appeared in 264 BCE

In the same year, a new period in the history of Rome began. The dispute between the Nadbrza River republic and Carthage, then the most significant naval power in the western part of the Mediterranean for influence in Sicily, evolved into an armed conflict. First Punic War (from the word punicus – “Carthaginian”) 23 years. Despite heavy losses, the Romans broke the maritime power of Carthage, and the disputed island became the first province of Rome. Thus, the city of Romulus went beyond Italy to continually conquer new lands for the next 350 years.

The first non-Imperial conquests were a response to assaults. The Gauls from Po were exposed to raids in Italy, and the Illyrian pirates attacked Roman merchants. After being beaten, the Romans faced Carthaginian general Hannibal, who in 218 BCE entered Italy starting the Second Punic War. For 14 years, Hannibal’s army stayed in Italy and despite several great victories (including Lake Trasimeno in 217 BCE and the in 216 BCE) failed to break Rome, which moved the war to Carthage. In 202 BCE, near Zama Scipio Africanus defeated Hannibal. Carthage lost the war and had to renounce most of its lands, including Spain. Rome became the first power in the Mediterranean world. He confirmed his superpower status in 197 BCE, massacring at the Cynoscephalae in Thessaly, the Macedonian army. Seven years later, under Magnesia in Asia Minor, Roman legions defeated the Seleucid army, the first power of the Hellenic world, proving that they were the best army in the world.

The Roman state began to grow rapidly. In 146 BCE, Carthage and Greece were finally conquered. In 133 BCE, the ruler of Pergamon in Asia Minor wrote Rome as a whole to Rome. In the same year, the Iberian city of Numantia fell, resisting the legions of the Tiber for many years. In 121 BCE, the Romans conquered southern Gaul, twenty years later Cilicia in Asia Minor, and in 96 BCE Cyrenaica bordering Egypt.

Rome’s military successes increased the prosperity of the higher social classes who purchased large landed estates. They worked in them slaves flowing in thousands thanks to the successes of Roman legions. Their work replaced the activities of small landowners who formed the core of the army. Staying for a long time in wars in distant countries, they lost their lands to great landowners. So there were fewer middle-class Romans, which had a terrible effect on the number of available recruits, due to the current property census for recruitment to the army. When the majority of the population became impoverished, the rich Romans began to imitate the slackers and the antique lifestyle of the great centres of the Hellenistic world. The growing gap between the poor and the rich caused a sharp social conflict. To heal the situation, one of the tribunes, Tiberius Gracchus, proposed in 133 BCE the agrarian reform that provided for giving to the poor a state land seized by the rich. The idea was met with strong resistance. Gracchus was murdered. 10 years later, his brother Gaius Gracchus tried to bring in poor reforms, but he shared the fate of Tiberius. At the end of the 2nd century BCE, Gaius Marius transformed the civil army, which suffered more from a lack of recruits, into a professional army, in which the poorest (proletarians) could also serve. Such a reformed army beat the Germanic tribes of Teutons and Cymbras that invaded Gaul in 103 and 102 BCE. Certainly, nobody expected then that Marius’s reform would bring the republic down.

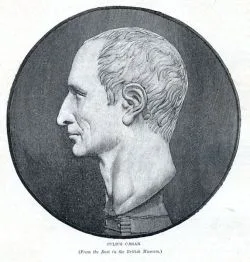

The problem of equipping veterans leaving their service was ultimately one of the most important reasons for the collapse of the republic. Soldiers, without any state guarantees, could hope for a peaceful old age only in the activities of their leaders. This addiction facilitated the use of the state army for private purposes. The great protagonists of this time Gaius Marius, Sulla, Julius Caesar, Pompey the Great, Marcus Crassus, Gaius Octavian, Marcus Lepidus, and Mark Antony initially sought to gain personal fame, like their ancestors for centuries, but later the struggle was fought for personal safety.

The losers in the civil war had no right to continue to exist. Sulla, who carried out extensive reform of the political system, came out victorious from the first clash in the 1980s between Marius and Sulla. Both during the civil war, they murdered their competitor’s supporters without mercy (proscription). Sulla tried to restore ancient virtues, but his intentions failed. In 79 BCE he gave up his dictatorship and died soon after. However, the country was plunged into war. In Spain, Sulla’s opponents were still fighting (Rome’s war with Sertorius). In the east, there were wars with Mithridates, and in 73 BCE a great slave uprising broke out in Italy under the leadership of Spartacus. After great successes in the east (including the final defeat of Mithridates and occupation of Syria) Pompey became the first figure in the republic.

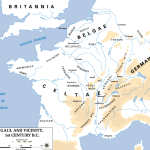

However, he was not strong enough to rule alone. In 60 BCE the first triumvirate was formed: Pompey, Julius Caesar and Crassus shared power in the country, while maintaining the entire facade of the republican system. The triumvirate survived until the death of Crassus at Carrhae in 53 BCE Caesar, who in 58-52 BCE he conquered Gaul, and Pompey was alone. In 50 BCE, Caesar entered Pompey’s controlled Italy despite the Senate’s ban, crossing the sacred border on the River Rubicon. The war between the two great chiefs embraced the entire empire. The main clash occurred in Greece, where Pompey suffered a defeat at Farsalos in 48 BCE It seemed that Caesar would become a monarch.

However, fate wanted differently and during the March Ides – March 15, 44 BCE Caesar was murdered. The killers wanted to restore the old rules governing the republic, but they miscalculated. Caesar gained immense popularity and his reforms had public support. The murderers had to take refuge on Capitol Hill to avoid self-trial. “Caesarians ” (followers of Caesar) seized power in the city.

Against Caesar’s killers: Mark Brutus and Gaius Cassius Longinus were Caesar’s two closest associates: Mark Antony and Marcus Lepidus and his adopted son and heir – Caesar Octavian who created the second triumvirate. In 42 BCE near Philippi in Macedonia, the killers of the conqueror of Gaul were defeated.

Soon after, Lepidus was removed from the triumvirate, and the empire was divided into two parts (Octavian ruled in the west, and Antony in the east). However, the division could not last forever. Antonius’ territorial bestowal on the sons of his mistress, Egyptian queen Cleopatra, became an excuse for Octavian to declare war. On September 31 BCE, in the naval battle of Actium, Octavian’s fleet defeated the fleet of Antony and Cleopatra. The following year, Octavian came to Egypt. Antony and Cleopatra committed suicide, and Caesar’s successor joined Egypt to the empire. Three years later, the Senate gave him the title augustus and a new system was created that modern researchers called principate.

It was implemented by Octavian Augustus, Caesar’s adopted son, a mediocre commander, but a brilliant politician and administrator “renewed republic” in 27 BCE introducing a system of government based on supreme authority over the army, tribal authority (from 23 BCE) and the office of the high priest, which was held by the emperor. August reduced the number of senators to 600 and introduced the separation of two states: equities and senatorial. The equities became the foundation of the imperial administration, assuming positions prohibited to senators (the most important are the prefects: fleet, grain supply, Egypt and the Praetorian Guard). Roman provinces were divided into senatorial and imperial ones. At the time, imperial worship also appeared, particularly strong in the provinces, initially associated with the cult of the goddess Roma. August provided his soldiers with a briefing after leaving the service. It allowed for a peaceful arrangement of life. Soldiers who were not Roman citizens before joining the army also received full citizenship as a reward.

August also marked the boundaries of the Roman Empire, which only slightly changed in the course of history. After Varus’s defeat in the Teutoburg Forest in Germany, the borders of the Empire leaned on the rivers: Euphrates, Rhine and Danube. The only ones who expanded its range were: Claudius, which took Britain and Trajan, who in turn mastered Dacia and Mesopotamia.

After the death of August, the scope of imperial power gradually increased, while the influence of the Senate gradually decreased. The greatest period in the history of imperial Rome is the so-called Antonine dynasty, meaning “the golden period”. The period of political stability was accompanied by economic development, visible above all in cities. The range of Latin gradually widened, primarily through the settlement of veterans who had to use Latin in the army. Roman law and education were also common. This resulted in the cultural unification of the western Mediterranean. In 212 CE this process was already so advanced that emperor Caracalla gave Roman citizenship to all inhabitants of the empire. The document issued by the emperor was called Constitutio Antoniniana (the so-called Edict of Caracalla, whose preparation is rather attributed to his predecessor and father, Septimius Severus). This edict, giving the full right of Roman citizenship to almost all the free population of the empire, Caracalla probably announced mainly for the popularity among the masses of the empire’s population, as well as for fiscal motivation (extending the taxation of Roman citizens to most of the population). By giving the Roman civitas, the idea of political solidarity and a religious community (a command to pray for the emperor to all deities of the empire) was achieved. Thanks to this, Constitutio significantly influenced the direction of further social development of the Empire.

In the 3rd century CE, there was an acute crisis, intensified between 235 and 270 CE The Empire was wiped out by continuous civil wars, which were accompanied by barbarian invasions. Fighting armies wreaked havoc among civilians and depopulation affected entire regions (Gaul, Dacia, Moesia and Thrace suffered the most). Many people also lost their lives as a result of the protracted plague. Progressing inflation and depreciation of the coin have destroyed the economy. A new factor emerged in religious life, Christianity, which at that time was in opposition to imperial power. The empire was restored to become Diocletian, who carried out far-reaching reforms in the army and political life of the empire. He fully deified imperial power, increased the number of provinces and thus facilitated their administration.

In addition, Diocletian divided the entire empire into two parts: Eastern and Western, thus creating the foundation for the final division an empire that occurred over a hundred years later. He also strengthened the defence of the borders by expanding the fortification system and created a tactical army whose task was to strengthen the frontier forces in the most endangered regions of the country. The Roman army increasingly consisted of the sons of former soldiers and barbarian troops. Diocletian also introduced maximum prices on many products, trying to reduce inflation in this way. Constantine the Great, another of the great rulers of the late empire, led to religious change, strongly favouring the hitherto fought Christianity. He also continued to reform Diocletian in the military sphere. However, immortality was gained thanks to the assumption, on the site of the former town of Byzantium, the new imperial capital: Constantinople. One of Constantine’s successors, Julian Apostate, tried to reverse history and renew the pagan religion. However, he ruled too short (18 months) for the reforms he had initiated to be effective. He died in the war against Persia.

The last of the great rulers of the empire was Theodosius the Great, which improved relations between the Empire and the Goths, suppressed the Arian opposition, banned pagan worship, and just before death led sanctioning the division of the empire into eastern and western parts, where the latter succumbed to invaders in 476 CE, officially ending the age of antiquity. There was still an attempt to restore the Empire, such as for Justinian the Great in the first half of the sixth century CE, but it did not survive his death. Although it was assumed to be 476 CE was the end of the Roman Empire, it can be said without a doubt that Rome has survived in some respects. This is primarily about the values that Latin civilization passed on to modern Europe and the fact that after the fall of Rome, Constantinople existed for almost a thousand years, and considered itself the legitimate heir of the Eternal City.