Chapters

Catilinarian conspiracy was the events of 63 BCE, when the impoverished politician Lucius Sergius Catilina tried to overthrow the rule of the consuls for a given year: Marcus Tullius Cicero and Gaius Antonius Hybrida and seize power. The description of events has survived to our times due to numerous source texts, especially Cicero’s speeches.

Background of events

In 67-62 BCE, when Pompey gained great fame by conquering and plundering in the East, Marcus Crassus took advantage of his absence from Rome by manipulating the clientele and using all means to gain primacy in political life. Crassus tried to achieve his political goals in the absence of a rival, whose successes he was particularly jealous of.

At the end of 66 BCE, Crassus secretly supported a plot to remove the consuls midway through the term of office for 65 BCE, seeing it as an opportunity to gain some benefits. In the political mess that arose then, he tried to take over the full dictatorial power. The driving force behind the plot was Lucius Sergius Catilina, a member of an impoverished old patrician family who grew rich through the Sullian massacres and blackmail in the province of Africa. The conspiracy for their happiness did not have any major consequences, and this was because little information was released. And although the Senate supported the investigation, Crassus was able to discontinue it with his influence.

Plot of Catilina – coup attempt

Catilina’s attempts to take over consulship

In 64 BCE Catilina submitted her candidacy for the consulate of 63 BCE, with the support of Crassus. To ensure a favourable reception, he devised a reform program geared towards drastically reducing debts. Those interested in it were mainly noble patricians (including Catilina himself), fallen equites and people with big financial problems. The Senate, concerned about the radical reform plan and the first triumvirate between Caesar, Pompey, and Crassus in 60 BCE, opposed Catilina’s candidacy Cicero. He was the so-called homo novus (“new man”), ie the first person in the family to sit in the Senate. Thanks to his oratory skills, eloquence and appropriate support, he obtained a political mandate and took the office of a consul. Cicero thus interrupted the multiple and continuous holding of the consul’s office, starting from 94 BCE, by nobles. During his tenure as Cicero’s consulate, Caesar and Crassus regularly hindered his political activity, putting forward many liberal reforms aimed at gaining popularity among the people.

Catilina did not give up the chance to take the highest office. Supported, as always out of hiding, by Caesar and Crassus, he again put forward his candidacy for the consulate, this time in 62 BCE. Again, his campaign was based on the complete cancellation of debts, seeking support among the poor, artisans and the particularly disadvantaged classes. People lacked water and bread, and there was no room for baking by hand in the apartments. However, Catilina again suffered a defeat with Cicero, who explained that the implementation of this social reform would violate traditional property relations. Once again, Cicero proved his genius and oratory skills and brought the centurial assembly (comitia centuriata) to his side.

Conspiracy started

The defeated Catilina, who showed up on the streets with Sulla and decaying farmers, again put forward a plan to overthrow legal power, which included, among other things, killing the incumbent consuls: Marcus Tullius Cicero and Gaius Antonius Hybrida. One of the factors driving Catilina to the plot was his dreams of rebuilding the prestige and political role of gens Sergia. In Etruria, Catilina had many henchmen who grouped their forces at Fiesole to march on Rome. Cicero learned about the coup d’état being prepared from a certain mistress of one of the conspirators. Despite the lack of evidence, Cicero did not hesitate to attack Catilina with the first of his famous speeches, the so-called “Catilinarian orations”.

How far will you (continue to) abuse our patience, Catiline? For how much longer will that rage of yours make a mockery of us? To what point will your unbridled audacity show itself? Did the nocturnal garrison on the Palatine, the watch patrols of the city, the fear of the people, the assemblies of all the good men, this most fortified place of holding the senate, the faces and expressions of all these people [the senators] not move you at all? Do you not realise that your plans lie revealed? Do you not see that your plot is already held in check by the knowledge of all these people? Do you think that any of us do not know what you did last night, what you did the night before, where you were, who you summoned, and what plans you made? O what times (we live in)! O what customs (we pursue)!

– Cicero, In Catilinam, I.1-2

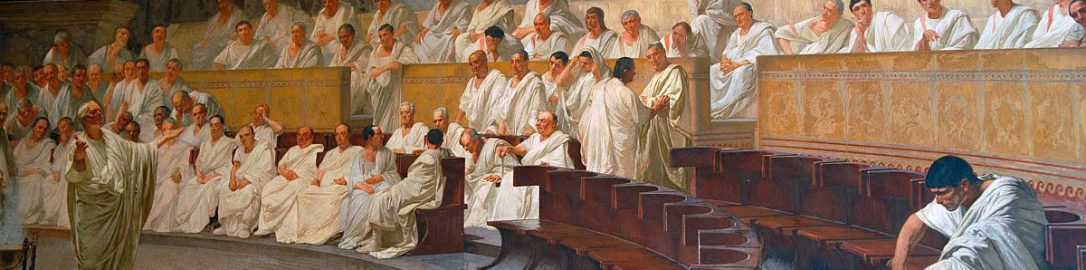

Catilina’s public accusation must have come as a shock to many senators. Catiline tried to speak in his defence, however, he was shouted down by the senators and decided to leave the Senate, Rome and went to Etruria, where his ally Gaius Manlius was gathering an army. Upon his arrival from the camp, Catilina assumed the title of consul.

At the same time in Rome, on the basis of written evidence, the Senate recognized Catilina and Manlius as public enemies (hostes). Moreover, Consul Gaius Antony Hybryda was sent at the head of the army to defeat the Catiline forces in Etruria; Cicero, in turn, was to defend the city against all rebels.

At that time, a delegation of Gauls – Allobrogans – arrived in Rome, who, dissatisfied with the abuses committed by the governor of Gaul of Narbonne, Fontey, wanted to ask the Senate for intercession. One of Catilina’s allies in Rome, praetor Publius Cornelius Lentulus Sura, tried to take advantage of the situation, encouraging them to oppose Rome and support the rebellion secretly. The Gauls, however, revealed the plans and helped Cicero track down those involved in the plot in Rome. Five people were arrested: Lentulus, Statilius, Gabinius, Cethegus and Caeparius.

The senate at the Concordia temple debated the fate of the imprisoned citizens. There were many proposals during the deliberations, from life imprisonment (Caesar) to execution without trial (Cicero). Finally, Cicero, using his special powers granted to him by the senate – senatus consultum ultimum – and guided by the good of his motherland, made a fiery speech, in which he proposed the execution of five conspirators by asphyxiation. His request was supported and Cicero gave the order to kill the captured conspirators. Finally, he was supposed to say: vixerunt, meaning “they lived”.

Battle in vicinity of Pistoria

The final battle between the consular army and the supporters of Catilina (in the number of about three thousand) took place near Pistoria. Despite the weak armament and the superiority of the enemy, the experienced veterans resisted for a long time. An unusual symbol raised their morale – Marius’s eagle, carried by his army during the victorious campaign against the Cimbrians (it is unknown where Catilina got it from). Eventually, after a fierce fight, Catilina’s people succumbed. When Catilina saw that the chances of winning were zero, he plunged into the fray. The rebel army was defeated and its leader was killed. Interestingly, when the bodies were counted, all of the Catiline soldiers had frontal wounds, which was evidence of the sheer fanaticism in the followers were fighting the adventurer. The proconsul, whose troops paid for the victory with great losses, ordered the head of Lucius Sergius to be beheaded. In Rome, it was shown as proof that the rebellion had been crushed.

Situation after suppression of rebellion

After the victorious battle, Cicero was greeted as the saviour of the homeland and was proud of his role as the defender of the republic. Evidence of a kind of self-amalgamation of Cicero is the preserved fragments of a poem he wrote in honour of the successful prevention of a coup. He wrote: “Oh, how happily Rome lived when I was a consul”. Interestingly, Cicero even asked his friends to recall his achievements. In one of his letters to Lucius Lucretius, he encouraged him to write a flattering account of the events of 63 BCE: “I came up with an incredible but, I think, not a reprehensible desire that my name would shine and become famous through your writing”. Cicero also hoped that a certain young Greek poet had written an epic on the subject.

His decision to kill Roman citizens without trial, however, was to take revenge. In December 59 BCE, a populist politician Publius Clodius Pulcher became the people’s tribune and enacted the law according to which everyone who killed a Roman citizen without trial is to be exiled. It was aimed precisely at Cicero, who was finally forced to go into exile in 58 BCE he built a temple dedicated to Libertas on the site.

Main sources of information

The main source of information about the Catiline plot is the work of Salustius who lived in the 1st century BCE – “War of Catiline” (Bellum Catilinae). It is worth mentioning that Salustius was not in Rome in 63 BCE, and he probably performed military service in another part of the country. In his description of events, Salustius relied on many sources, including the writings and speeches of Cicero, for whom he was not very fond of.

Of course, another very important source of knowledge about the plot are the preserved speeches of Cicero. Two of them he delivered at the people’s assemblies; he delivered the other two in the Senate, the most famous of which took place on November 8 and it was she who decided to leave Rome by Catiline.

Interestingly, thanks to the preserved accidentally private letters of Cicero, we know that even before the conspiracy began, he even counted on a certain political alliance with Catilina; he even considered his defence in court.

Catilina as person

After the death of Catilina, many poor Romans viewed him with respect and did not treat him as a traitor and a villain (as Cicero spoke of him). However, the Roman aristocracy had a different opinion.

Salustius in his work mentions that Catilina was distinguished by courage and resistance to pain and discomfort; at the same time, however, he personified the vices of Rome of his time – corruption and extortion. To this day, Catilina appears to us as a villainous figure, ready for betrayal.

When describing the plot of Catilina, Sallust uses the described event as evidence that the Roman state lost its former values, which was caused by an excess of wealth and the lack of a real competitor in the international arena.

The historian attributes to Catilina countless crimes and atrocities, including the drinking of the blood of a consecrated child. Later historians such as Florus and Cassius Dio, who lived in later times, merely rewritten the claims of earlier historians. Even though the name of Catilina to this day is associated with all the worst, many Romans viewed it with respect until the end of Rome. Cicero himself writes in his reflections that Catilina was an enigmatic figure, characterized by both noble qualities and terrible crimes. On the one hand, Catilina tried at all costs to achieve something extraordinary and rebuild the position of his family. On the other hand, he was the epitome of courage, firmness in reaching goals and honour. He would rather die in battle than be judged by the system he wanted to overthrow.