Chapters

Lucius Sergius Catilina was born in 108 BCE. He was a Roman senator in the 1st century BCE who went down in history as the initiator of a conspiracy called the Conspiracy of Catilina. This plot was aimed at overthrowing the republic and the aristocratic Senate. However, the famous speaker and politician Cicero prevented him as a last resort.

Family

Catilina was born into one of the oldest families of Roman patricians – gens Sergia. Although the family had many ancestors with the title of consul, it was gradually deteriorating both socially and financially. Virgil then “gave” in “Aeneid” to this ancestral lineage, Sergestus, who was to come to Italy with Aeneas. Such a procedure was surely aimed at getting the family out of the crisis and underlining its former importance. The last consul in the family was Gnaeus Sergius Fidenas Coxo in 380 BCE starting a conspiracy. It was the dreams of rebuilding the prestige and political role of the Sergia family that led Catilina to decide to set up a conspiracy.

Military service and political career

Catilina was a capable commander with an outstanding military career. He served during the war with allies (91-88 BCE) with Gnaeus Pompey the Great and Cicero under the command of Gnaeus Pompey Strabo in 89 BCE. During the regime of Gaius Marius, Lucius Cornelius Cinna and Gnaeus Papirius Carbo, Catilina did not play any significant role, but he had a stable and secure political position. During the First Civil War (84-81 BCE) he supported Lucius Cornelius Sulla. The enactment of the prescription revealed the worst qualities of a young and ambitious politician. He allegedly tortured, mutilated and decapitated his brother-in-law, Marius Gratidianus in the tomb of Catullus. Then Catilina was to carry the head of the dead man through the streets of Rome, take it and throw it at Sulla’s feet in the temple of Apollo. He was also accused of the murder of his first wife and son, which he was to do in order to marry the rich and beautiful Aurelia Orestilla, the daughter of the consul for 71 BCE – Gnaeus Aufidius Orestes.

In the early 70s, he served abroad, possibly with Publius Servilius Watia Izauri in Cilicia. In 73 BCE he was brought for adultery with the Vestal girl Fabia, who was the half-sister of Cicero’s wife, Terentia. Ultimately, however, Quintus Lutacius, the Capitoline Catullian, leader of the Optimates, acquitted Catilina.

In 68 BCE he became praetor, and for the next two years, he was the propreator of the Africa Proconsularis province. In 66 BCE he returned to the capital and submitted his candidacy in the consular elections. However, a delegation from the African province made accusations of alleged abuses, and the 66 BCE consul – Lucius Volcatius Tullus – did not agree to Catilina’s candidacy in the next election. Catilina was finally brought to trial in 65 BCE, where she received great support from many influential politicians, including former consuls. The current consul of this year also expressed his support – Lucius Manlius Torquatus and Cicero. Ultimately, he was pardoned for the charges against him.

Involvement in the first conspiracies

In late 66 BCE, Marcus Licinius Crassus secretly endorsed a conspiracy to remove the consuls midway through 65 BCE. seeing it as an opportunity to obtain certain benefits. He was the soul of this conspiracy, wanting to overthrow the power of Pompey the Great, who was then staying outside Rome. Julius Caesar and Gnaeus Calpurnius Piso were also present. The first according to the plan was to go to Egypt in order to liquidate that kingdom and gain its resources. The second of them was to take over the management of Spain. Crassus himself was to take over the dictatorship and restore two consuls dismissed due to electoral abuses and corruption (ambitus in accordance with Lex Acilia Calpurnia): Publius Autronius Petus and Publius Cornelius Sulla – the former nephew of the former dictator). The whole plot was based on the assassination of two new consuls – Lucius Aurelius Cotta and Lucius Manlius Torquatus – chosen as if in an emergency to replace Petus and Sulla. The removal of those consuls, elected for 65 BCE, was a pretext for a conspiracy, which can be safely called a coup d’état. It failed because the Senate somehow found out about these intentions (planned for the day of taking over the consulate, ie on January 1). The implementation of the plans was postponed to February 5, but also then it ended in nothing, probably because Crassus did not show up, and as a result, Caesar did not give the agreed sign. Another account, saying that Catilina gave a sign too early before the conspirators had even gathered, aims to acquit Caesar and Crassus. The driving force behind the conspiracy was always Catiline, who was possibly inspired by the popular Senate party (one of their leaders was Julius Caesar) seeking to weaken the optimists (Pompey had an important position in this party).

Plot of Catilina – attempted coup d’état

In 64 BCE Catilina decided to run again in the consular elections for 63 BCE. He based his election campaign on populist slogans, which were mainly intended for people like himself – impoverished aristocrats (he promised to abolish debts) and discouraged Sulla war veterans. Experienced soldiers waited for funding for their purses and were ready to move under the command of the “new Sulla”. The state debt was the highest in years, which had a bad effect on the province in Italy. A huge number of plebeian farmers lost their possessions and were forced to move to the city, where they “strengthened” the urban poor. Catilina’s populist slogans about improving the existence of the impoverished aristocracy, veterans and commoners found fertile ground.

Despite this, Catilina lost the election. One of the consuls was Marcus Tullius Cicero, an opponent of the popular. Then Catilina decided to achieve the goal – gaining power – through a coup d’état. There are many indications that Catilina wanted to provoke slave revolts in several regions of Italy in order to destabilize the situation. In addition, the rebels made a deal with the Allobrog tribe of Narbonne Gaul, who were to send their warriors across the Alps. However, the backbone of Catilina’s forces were Sulla’s former legionaries living in Etruria. His associate Gaius Manlius began forming troops out of them in the vicinity of the city of Faesulae. At that time, there were almost no troops in Italy, because the Senate was afraid that the leaders would use them to put pressure on the rulers. The conspirators also planned to kidnap Pompey’s children as hostages to protect themselves against his possible intervention. There were also planned numerous murders of senators and people reluctant to Catilina and his supporters. After the killings, Catiline was to join Manlius’ army and take Rome together. It is also possible that they wanted to organize an attack on Cicero (he was to be made by Gaius Cornelius and Lucius Vargunteius in the morning of November 7, 63 BCE). Fortunately for Cicero, his informant – Senator Quintus Curius – through his lover Fulwia learned about the plans of the conspirators and informed Cicero in time. He posted a guard at the door of the house, which scared the murderers and prevented a murder.

Meanwhile, the envoys of the Allobrogs had arrived in Rome. Ultimately, they came to the conclusion that it was better to remain allies of the republic than to enter into an alliance with an untrustworthy adventurer. The Gauls confirmed that an attempt was made to draw them into the plot.

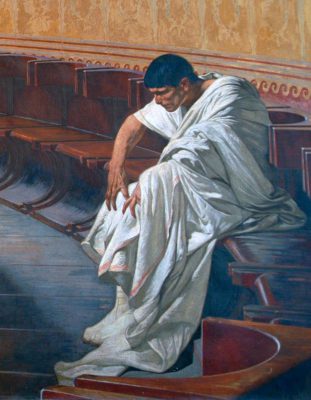

The next day, Cicero convened the Senate at the temple of Jupiter Stator and surrounded him with armed guards. To her great surprise, Catilina, participating in the deliberations, with her own ears heard the famous speech of Cicero – “cCatiline Orations ” (there were four – In Catilinam I – IV). The speech itself was highly coloured (he spoke of plans to set Rome on fire and kill the optimates), but the mere mention of intentions to provoke a slave revolt was enough to arouse fear and fury among the Romans, who remembered the recent the rise of Spartacus. During the beautiful speech of Cicero, the surprised and outraged senators moved away from the conspirator, leaving him alone in the background of the seats. Outraged Catilina, he urged the senators to remember the history and achievements of his famous family, accusing Cicero of lying and slandering the good name of his family. In the end, he used strong words and left the meeting and went to his home. That same night he left Rome and, under the guise of voluntary exile to Massilia (as requested by Cicero), went to the camp of the conspirators in Etruria to implement revolutionary plans. Five important conspirators – Lentulus, Cetegus, Statilius, Gabinius and Ceparius – were imprisoned in Tulianum prison. Soon they were executed on the orders of Cicero (in 58 BCE he was expelled for a year for this act, considering that he had rendered the sentence unlawfully).

The figure of the hunched-over Catilina and the empty spaces next to it clearly shows the moment of the meeting.

Catilina headed his supporters. He decided to break through to the north, but soon the army of proconsul Gaius Antony, sent by the Senate, caught up with him. The clash took place near Pistoria in 62 BCE. Despite the weak armament and the superiority of the enemy, the experienced veterans resisted for a long time. Their morale was raised by an unusual symbol – Marius’s eagle, carried by his army during the victorious campaign against the Cimbrians (it is unknown where Catilina got it from). Eventually, after a fierce fight, Catilina’s people succumbed. When Catilina saw that the chances of winning were zero, he plunged into the fray. The rebel army was defeated and its leader was killed. Interestingly, when the bodies were counted, all of the Catiline soldiers had frontal wounds, which was evidence of the sheer fanaticism the followers were fighting of the adventurer. The proconsul, whose troops paid for the victory with great losses, ordered the head of Lucius Sergius to be beheaded. In Rome, it was shown as proof that the rebellion had been crushed.

Legacy

After the death of Catilina, many poor Romans viewed him with respect and did not treat him as a traitor and a villain (as Cicero spoke of him). However, the Roman aristocracy had a different opinion. In summing up the plot, Salustius concluded that he was the embodiment of all that was bad in the declining republic. The historian attributes to Catilina countless crimes and atrocities, including the drinking of the blood of a consecrated child. Later historians such as Florus and Cassius Dio, who lived in later times, merely rewritten the claims of earlier historians. Even though the name of Catilina to this day is associated with all the worst, many Romans viewed it with respect until the end of Rome. Cicero himself writes in his reflections that Catilina was an enigmatic figure, characterized by both noble qualities and terrible crimes. On the one hand, Catilina tried at all costs to achieve something extraordinary and rebuild the position of her family. On the other hand, he was the epitome of courage, firmness in reaching goals and honour. He would rather die in battle than be judged by the system he wanted to overthrow.