Chapters

The Greek physician Hippocrates (c. 460-377 BCE) stated that there is no better place to gain knowledge and experience in the medical profession than the army taking part in military expeditions. It is in the barracks that a novice medic deals with a multitude of injuries, infections and operations. Thanks to this, a student of medicine can learn the anatomy of the human body and look for the best remedies for ailments.

Certainly, the Greeks were pioneers in military medicine. It was Hellenic influences that “instilled” the existence of this field in Roman legions. We do not have much information about early Roman field medicine. Before the Romans established contacts with the Greeks, the Roman army did not have any organized medical care, and any wounds of the soldiers were treated by their comrades – provided they had some knowledge. If the wounded person was unable to walk, he was often left or taken to a nearby town. The chief himself was responsible for the condition of the wounded and their removal from the battlefield, who could also locate them in nearby houses. However, with the growth of the Roman state and military operations abroad, the development of the issue of military medicine was significant.

With the establishment of closer contacts with the Greeks and the conquest of the Peloponnesian Peninsula and Hellas, a lot of Greek slaves began to arrive in Rome, with a lot of knowledge, including in the field of medicine. It was mainly them who dealt with treatment in cities and teaching science to other adepts of medicine. However, it was still impossible to talk about the existence of professional medical assistance in the Roman army.

In the middle of the 1st century BCE, Julius Caesar, leading the conquest of Gaul (58-51 BCE), mentions in “About the Gallic War” that the wounded were left in the camp1, while the rest of the army continued marching. Other sources say that unfit soldiers were simply released to cities with specialized medical centres – not yet existing in the army.

With the advent of the reign of Octavian Augustus (27 BCE – 14 CE) a professional Roman army was born, in which the already 16-year-old Romans could seek a military career. In return for good service, the recruit could count on a fixed salary, which was paid from a special aerarium militare vault. In order to raise money, an inheritance tax of 5% and a tax on sale of auctions of 1% were imposed on the treasury.

Furthermore, he restricted all the soldiery everywhere to a fixed scale of pay and allowances, designating the duration of their service and the rewards on its completion according to each man’s rank, in order to keep them from being tempted to revolution after their discharge either by age or poverty. To have funds ready at all times without difficulty for maintaining the soldiers and paying the rewards due to them, he established a military treasury, supported by new taxes.

For the first time, a young man could start military service and use his skills and knowledge in a specific field (acquired in society) for the needs of the Roman army. This is how, inter alia, specialization of a medic (medicus) who could dress wounds and perform surgeries. Thus, the morale of the soldiers was higher and the army more efficient. Moreover, Octavian Augustus began creating the first medical corps, and the medics played an important role in the army for the first time. The medics could also count on special benefits and land after their termination of service. Also given medici equity status (dignitas equestris); both private and public. Thus, they became full citizens and had the right to wear an equestrian ring.

It is worth mentioning that when joining the army, recruits had to undergo a mandatory health assessment; thus, only healthy and strong men were allowed access to the army.

The term medicus refers to the position of milites medici, i.e. a soldier relieved of his duties. Terms like medicus legionis said that the medic looked after the entire legion, medicus cohortis was responsible for the cohort, and e.g. medici alarum for the cavalry unit (alae).

It seems that medicus was in fact a soldier with additional skills who looked after the wounded and performed surgeries. What’s more, he left the main army during the march and stayed in temporary marching hospitals, the so-called valetudinaria or aesculapia, where more serious wounds and diseases were dealt with.

Along with the Roman legions, skilled medics most certainly marched in the time of physician Galen (c. 130-200 CE). Galen – of Greek origin – had a tremendous influence on the development of medicine, and he was certainly one of the greatest medics of ancient times. He had his first “apprenticeships” in Pergamon, where he worked at the gladiators’ school. There he cared for the health of gladiators and took his first steps in anatomy and surgery. He also owes his knowledge to autopsies conducted in Greece, most often of monkeys. While conducting research, Galen gained enormous knowledge, which gave him respect and authority in the field of medicine at that time. Galen mentioned, among other things, how to dress wounds, what herbs to use, what plants are a cure for disease and what food will restore the strength and efficiency of the wounded. Galen’s fame even reached the imperial court; Emperor Marcus Aurelius decided to appoint him to the position of court medic.

With the advent of medicine, veterinary care was also born. praefectus castrorum was responsible for the organized field hospitals, when optio valentudinarii was responsible for it.

In the 2nd century CE, virtually all of the larger (except the smallest) camps and Roman units had permanent medical personnel. Naturally, hospitals and staff were larger in legions than in support units. There were medics, assistants, people making ointments/spreads and producing bandages.

The so-called capsarii were “first contact” medics, that is, they dressed wounds, moved boxes with bandages (the so-called capsa), transported the injured to the hospital and helped a competent physician in providing professional help injured. He himself did not perform any operations. It is worth mentioning that – based on archaeological research – medical supplies and transport vehicles for transporting the wounded were most often found between the marching columns of soldiers.

Medicus was a Roman medic who directly managed the medical structures in the army/camp. Most often he was a liberated Greek slave or simply had a Greek education in the matter of healing. There were doctors with various specializations (including urology, ophthalmology, etc.).

There were also hospital administrators (optiovaletudinarii), secretaries (librarii), instructors (discentes), magicians and herpetologists (marsus), vets (pequarius), vets for e.g. foals (pollio), vets for camels (ad/cum camellos). As you can see, the Roman army had a really well-organized medical service.

Often in Roman inscriptions one can find the function medici ordinarii which refers to the lowest rank of a military doctor. However, it is worth paying attention to the word ordinarii, which suggests that this was an “ordinary” specialist and was not as respected as medicus. The so-called medicus duplicarius (“double wage medic”) and milites sesquiplicarii (“soldier’s 1.5 times wage”), whose wages are certain to they could also receive legionary medics.

Care for the wounded in battle

As shown in the relief from Trajan’s Column, medical personnel were also present during the battle. The medical staff was behind the banners, not far from the headquarters. Certainly, before the wounded were brought to the “battle hospital”, they first received first aid from capsaria – medical helpers. Some soldiers volunteered and brought the wounded from the battlefield on their horses. In return, they could count on additional remuneration; from everyone saved. Capsarii bandaged the wounded with the so-called fascia, which was worn in capsae.

From the field hospital, the wounded were transported on horse-drawn carts to local stationary camp hospitals. There, too, surgeons (medici vulnerarii) and medici took care of their health. The wounded were given beds (the largest hospitals had up to 500 beds), and in the absence of places, the commander placed the injured in civilian buildings.

Roman hospitals

In the work “On the demarcation of military camps” (De MunitionibusCastrorum, from the 1st-4th century CE2) we find information that a typical Roman hospital (valetudinarium) could accommodate 200 people, was hastily built and not well equipped. This proves that such hospitals were originally only small camps built “fast” for medical purposes.

Over time, however, such poorly equipped hospitals made of tents turned into permanent wooden or stone structures that were built along main roads. Over time, hospitals became part of a large camp. They were usually built near the outer walls of the fort, in a secluded place.

The standard valetudinarium was a rectangular structure with four wings, which could accommodate from 6 to 10% of the 5,000 legionaries. A typical permanent hospital had a large hall, reception, medicine room, kitchen, staff quarters, and a backroom with latrines, and a laundry room. In the former Roman camp in Baden, there was a hospital with a facade, a column portico and 14 rooms.

According to the researchers, the most important aspect of the hospital’s demarcation was to ensure good phytosanitary conditions and access to clean water. For their work, medics needed isolated rooms and access to freshwater. Already Marcus Terentius Varro (116 – 27 BCE) was aware of the existence of “little invisible creatures”, which nest, for example, in swamps, and after getting into the body through the mouth or nose can be a source of disease. For this purpose, for example, it was recommended to set up camps far from the marshes.

For example, in order to get rid of germs, surgical instruments were boiled in water in the operating room. In the event that another patient was to be operated on, the previously used instruments were disinfected again in boiling water. The wounds, in turn, were disinfected with vinegar. This proves the Romans’ knowledge of hygiene and germ removal.

Plants and herbs used as medicines were also grown near field hospitals. For example, in Bearsden, Scotland, celery residues were found that were used for medical purposes.

In addition to hospitals, there were baths and latrines in the Roman army. Originally, both of these buildings were outside the camp; over time, however, they were also built inside the defensive walls. In the baths, the soldiers had time for relaxation and hygiene. Each fort had at least one public toilet, which was located where the terrain fell, thus avoiding the accumulation of waste and using gravity. The sewage was discharged through special ditches under the walls and collected in a specially dug ditch. In Bearsden, scientists found extremely valuable archaeological material – the remains of a sewage collection site, which turned out to be a real treasury of knowledge about the balanced and vegetarian diet of the Romans.

Naturally, the Romans did not have as much knowledge of hygiene as we do today. Among other things, the Romans often placed a toilet near the kitchen, which, as we know, caused the spread of germs and diseases. It should be emphasized, however, that at that time people were aware of the need to get rid of excrement and waste and to collect them outside their place of stay. However, as shown by the discoveries of scientists in Carlisle (northern England), sometimes faeces were also found in places where there were no latrines. What’s more, in Pompeii even a wall of graffiti has been preserved asking not to poop. This proves that legionaries did not always defecate in latrines. For this reason, there were numerous flies in the camp, and salmonella, typhoid and diarrhoea were transmitted.

It is worth mentioning that, for example, the Roman author Vegetius (4th century CE) in his work “On Military Art” mentions that the army should always have access to clean and drinking water and take into account weather conditions. Moreover, he advised against marches in the hot sun and frosty weather.

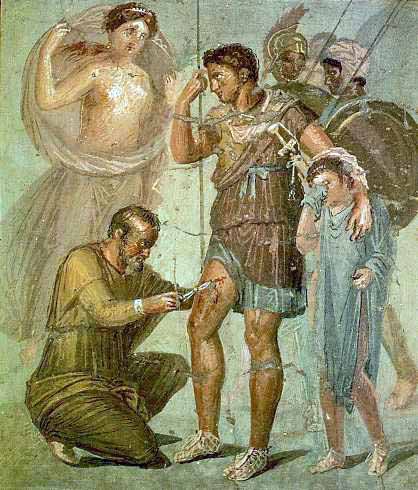

Operations and treatments

Celsus describes what the ideal candidate for a surgeon should look like. First of all, it must not be old and must have firm, non-shaky hands. He should be able to use both hands equally well; not be too rash with the operation; have good eyesight; do not be afraid and not respond to the screams of the injured person; identify with the patient, but not to such an extent as to experience suffering with him3.

One of the most common operations or medical procedures in the Roman army was the removal of foreign bodies from tissues – arrows, and stone or lead bullets. Celsus emphasized that the most important goal of the procedure is to avoid haemorrhage and inflammation. For this, he recommended using vinegar as a blood flow stop; however, he noted that in order to avoid inflammation it is important to maintain a constant blood flow. Moreover, inflammation will develop when bone, tendon, cartilage or muscle are damaged. If the wound is in a soft part of the body, it is important to sew it up; however, suturing is not recommended when the wound becomes unsealed. Celsus also advised that wide linen bandages should be used to protect and cover not only the wound but also its surroundings.

Another often surgery that Roman doctors had to perform was amputation. Celsus is one of the first physicians to mention the benefits of amputation above or at the height of a serious wound, especially when gangrene has developed. However, he recommended that the amputation be carried out at the height of a healthy body so as to cut the bone and then keep more flesh on the other side to cover the bone. It is worth mentioning that Celsus advised avoiding bathing while the wound is still fresh. Water, moisture and dirt could facilitate the formation of gangrene. Moreover, it was also a good idea to gently rub the area around the wound4.

Of course, various types of painkillers were used during the operation, or just to relieve the pain of the injured / sick person. The most commonly used were poppy opium and black henbane seeds, which often caused hallucinations and “draining” of the patient.

However, the most important thing in the course of the operation was to perform it as soon as possible, not to completely relieve the patient’s pain. The surgeon also needed to have good and strong assistants who might sometimes be needed to hold down a struggling patient.

In ancient Rome, skull trepanations were also carried out. Galen mentions that it is a good treatment for broken bones in the skull to relieve pressure in the head and reduce headaches. It happened, however, that Roman medics used this method to treat epilepsy, migraine headaches or paralysis5.

Conjunctivitis was a common health problem that soldiers complained about. For this purpose, various types of ointments were used. In one of the documents confirming the dismissal of a certain Tryphon, son of Dionysius, a specialist in weaving, we learn that the reason for leaving the army was the deterioration of eyesight and the need to diagnose the disease in Alexandria, Egypt. It is not entirely clear whether the man was a regular soldier; but certainly, problems such as visual impairment did occur and military personnel received such “medical certificates” or passes.

Other procedures that were performed in ancient Rome were: hemostasis (stopping bleeding), tracheostomy, operations in the case of bone dislocations or fractures, and even plastic surgery.

Herbs and other medications

The Romans also dealt with pharmacology and the search for drugs for numerous diseases plaguing soldiers and citizens of the Empire. Many of the herbs used by the Romans were known to the Greeks, from which they took most of their knowledge. Below are some of the valued plants:

- Aloe – healed wounds (applied dry); removed ulcers, had a cleaning effect; effective for baldness.

- Garlic – valued for its positive effects on health, especially the heart.

- St. John’s wort (hypericum perforatum) – was used for blood poisoning and bites of poisonous animals.

- Italian fennel (Ippomarathron) – had positive effects on painful urination and kidney stones.

- Figs – effective for healing wounds.

- Bitterness (Gentiane) – valued for its warming effect; it has a beneficial effect on the liver and was used in the case of bites of poisonous animals; treated ulcers and inflammation of the eyes.

- Fenugreek – was used to make compresses and had a beneficial effect on pneumonia.

- Smooth licorice (Glukoriza) – supposedly soothes problems with the stomach, chest organs, liver, kidneys and bladder.

- Great Oman (Elecampane) – effective for digestion.

- Curly rhubarb (Ra) – ideal for flatulence, convulsions, stomach problems, sciatica, asthma, and dysentery.

- Sage – valued mainly for religious reasons.

- Sylphion (Silphium) – in ancient times it was extremely popular. Its juice was one of the main exports of the ancient Greek colony of Kyrene (today Libya), and it was known and used throughout the Mediterranean. This plant was considered to be a panacea, an antiseptic, laxative, contraceptive and abortive agent, and also a spice. It was covered by a state monopoly and its trade was strictly controlled.

- Willow-tree leaf extract had anti-inflammatory properties.

Moreover, Roman doctors knew that the basis of a strong and healthy army was a well-chosen diet. Hence, good food for soldiers was taken care of. The diet included grains, cheese, wine, fresh fruit and vegetables, and whole-grain bread, which was valued as food. Every soldier was right panis militaris. The wounded and the sick were given peas, lentils and figs.

Roman authors also advised avoiding overeating during starvation. This was the case, according to Appian, in 43 BCE during the siege of Mutina. Soldiers who suffered from overeating were usually given a concentrated wine and olive oil, which eliminated the negative effects of “gluttony”.

Archaeological materials

We have a lot of information about the Roman army thanks to the preserved and discovered Roman artefacts found in the areas of former camps and marching forts and battlefields. The finds include numerous tools and devices used by medics, e.g. during an operation. We can distinguish: probes, spatulas, spoons, tweezers, scalpels, curved and straight needles, medical glassware, small vessels and boxes for ointments.

One of the most interesting excavations, where numerous traces of a Roman hospital were found, is Baden (Germany), where, among others, catheters, spoons and much more. Moreover, discovered coins that clearly suggested that the camp was active in the 2nd century CE. There were also tombstone inscriptions mentioning soldiers of the type medicus ordinaries, medicus legionis or medicus cohortis.

Another military hospital was located in Vetera (now Xanten, Germany). There were also found rooms full of medical instruments, operating theatres, sick rooms and dissecting rooms. Among the tools discovered include levers and tongs for extracting projectiles from the body.

A large base of knowledge about medicine in the Roman world is the works of Galen, Celsus, Vegetius, Oribasius (the doctor of the Emperor Julian the Apostate) and the Byzantine surgeon Paul of Aegina.

Tools used in the Roman army

| Rectal speculum. The earliest mention of this tool is from Hippocrates, who mentions that when the patient is lying on their back, the doctor can use the tool to assess the degree of ulceration in the intestine. |

| levers bone. Galen mentions that these tools allow broken bones to frame and remove the teeth. |

| Forceps to remove pieces of bone. It was recommended to remove broken bones with fingers first and then use a tool. |

| Roman Bubbles (cucurbitulae). Larger ones were placed on large parts of the body, such as the back or thighs. The smaller ones were used on the hands. |

| Tubes to prevent spasms and adhesions. After surgery on the nose, anus, and vagina, a bronze or lead tube was used to drain fluids and administer medications. |

| Enema Tool. |

| A cauterizing plate (ferrum candens). Medics of ancient times used many varieties of this device. Hot cauterizers are still used today to stop tissue or arterial bleeding. |

| Tool tray. |

| A catheter used to unblock a blocked urinary tract and allow urine to drain. The early forms were pipes made of bronze and steel; later versions took the form of a narrow S for men and a simple S for women. |

| Obstetric hooks (hamus, acutus). They were frequently mentioned in Greek and Roman literature. Both blunt and sharp versions of the tool were used, and they were used in exactly the same way as they are today. |

| Depilatory forceps. |

| forceps to remove the language. Greek medicine expert – Aetius – recalls how he performed surgery to remove the language. First firmly compressed language using the tongs to prevent bleeding, and then it was cut off. |

| Scalpels were made of bronze or steel and were of various lengths. Typically, the larger ones were used for long and deep cuts in the soft parts of the body. For more precise and smaller cuts, shorter blade scalpels were used. |

| Operational scissors (forfex). Ancient sources mention the use of such scissors to cut the patient’s hair and obtain more convenient access to the skin. Only a few accounts mention the use of tissue-cutting tools. |

| Tools for mixing drugs/ointments and applying them to wounds. They were also used by artists to mix colours. |

| Drug delivery tool. Also used for measuring and mixing medications. |