Chapters

Roman funeral (funus), since the beginning of the existence of Roman statehood, has been divided in two ways to send the dead away: smoking and burying. Initially, both were used with the same frequency, but over time, smoking gained the advantage since around the 5th century BCE.

According to Pliny and Cicero, not cremation, but inhumation was the original form of burial. However, dating from the eighth to sixth century BCE Sepulcretum at Via Sacra in the Roman Forum, contains both cremation and inhumation graves.

Both rites have been practiced since the adoption of the law of XII tables. According to Lucretius, three types of burial were practised during the late republic – cremation, inhumation and embalming. Pliny reports that many Romans were faithful to inhumation – e.g. Gens Cornelia, of whom Sulla was the first cremated member. They were buried at Via Appia in the tomb of Cornelia Scipionis between the 3rd and 2nd century BCE. However, before – until 400 BCE, cremation was a normal practice. This was also the case in the 1st century CE. This is evidenced by columbaria with niches for ashtrays and funeral altars containing remains of cremation.

In the times of Hadrian there was a sudden and rapid development of carved sarcophagi, which indicates a gradual departure from cremation in favor of inhumination in the second century, and in the third century it also spread in the provinces. This does not mean, however, a complete departure from body-smoking, but rather a demonstration of wealth, because the sarcophagi were also found ashes. In Etruria, both forms of burial were practiced in parallel and both urns and sarcophagi were richly decorated. The change was not related to Judaic or Christian influence.

Inhumation may have been an expression of respect for the body, which was the temple of the immortal soul and personality. Although mummification was known from the time of Lucretius until the late Republic, it was almost never practiced. In Italy, it was considered a foreign custom. According to Tacitus, Poppaea’s body was not only buried, not cremated, but also embalmed. A confirmed example of this type of burial was discovered in February 1964 near the Via Cassia. The tomb dated to the mid-2nd century CE and contained the preserved body of a 7-8-year-old girl. The deceased suffered from rickets and likely died of tuberculosis. She wore a necklace, ring, and earrings, and the tomb contained her toys—an ivory doll and miniature vessels. The body rested in a marble sarcophagus carved with hunting scenes in the style of the 2nd century CE.

It was possible that she was the child of a Roman official in Egypt, where she died and her embalmed body was brought to Rome. However, there were qualified balsamists in the City, so she might as well die in Rome. Two female mummies were discovered on Via Appia during the Renaissance – both crafted in Egyptian style, including a painted mask. Five other mummies were discovered in the provinces. It is possible that this was associated with the local worship of Egyptian deities – Isis and Serapis, the influx of immigrants from Egypt, or the wish of the deceased.

In the Roman state, due to spectacle, two types of funerals were distinguished:

- funus translaticium, very modest, was held without ceremony. The body of the deceased after washing was taken out before dawn and thrown into one of the common graves, or rather pits (puticoli), seated near the port of Esquilinia, on which the patron’s gardens were built in the first century BCE.

- funus indictivum, festive, which only the richest could afford. The procedure is described below.

Burial

As the dying person slowly made his life, one of his relatives approached his mouth to take his last breath from him, while the other participants raised a lament, calling on the name of the one who was just going to the afterlife. Then the body was laid on the floor and the fire was put out in a home fire. In the meantime, a relative of the deceased was performing administrative activities, namely reporting death at the office at the temple Venus Libitina. The applicant was required to pay a certain amount, called lucar Libitinae. Then the clerk (libitinarius) entered the name on the list of deceased people and accepted the funeral order. To complete the formalities, you still had to pay pollinctores, who anointed the washed body, praeficae, tears, tibicines – musicians playing the aulos and vespilones carrying a casket.

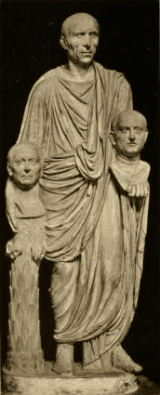

The embalming of corpses, mentioned above, was done by pollinctores. The scope of his services also includes casting a posthumous wax mask (imago cera), applied to the deceased on his face, while his body was exposed to the public for a period of 3 to 7 days.

The body of the deceased was dressed in a toga, appropriate to his civic status. It was unacceptable to overlook the obole that was put into the mouth of the deceased so that he could pay for Charon’s service.

The bed with the body (lectus funebris) was placed in the atrium, feet directed towards the front door. Family and friends watched around. Lamps or slaves with burning torches were placed at the corpse.

Branches of cypress or pine were hung outside, which informed passers-by about the calamity that hit the household.

The famous Law of the Twelfth Tablets introduced certain restrictions on the funeral itself. According to the recipes, the gold had to be removed from the mouth of the deceased, but when the body was burned, it was carried out after collecting the remains to the urn. In addition, in the case of burning corpses, after collecting the ashes and placing them in the urn, funeral ceremonies were to be carried out again. This costly privilege was lifted later.

The funeral procession (exsequiae) was opened by musicians, followed by slaves carrying torches and weeping. If the deceased held any office during his lifetime, there were also liqueurs in black costumes, and their inherent attribute, bundles of rods, was directed to the ground. Actors also took part in the retinue, whose task was to recount stories taken from the life of the deceased. Mimes in masks resembling the face of a dead man, while recreating scenes from his life. Then followed customers in the masks imposed on the face of the deceased’s ancestors. Sometimes there were people in masks of ancestors of other families, related to the family of the deceased. Behind them war spoils were carried, if they were obtained, the insignia of the dead’s power and items close to him. It was here that the main hero of this sad celebration followed. The next places in the conduct were occupied by: family, friends, freedmen, officials, the Senate, and the funeral procession was closed by the crowd.

If the deceased held office during his lifetime, the procession went through the Roman Forum, where a short stop took place. People in the masks of the deceased’s ancestors occupied in curled chairs, and the son or another close person gave a funeral speech (laudatio funebris). From the Forum, they were directed to the place where the corpse was to be laid or burned (ustrinum). It is worth mentioning that the burial place was outside of Rome, because Act XII tables, forbidding burying the dead in the city. During the monarchy, Eskwilin was burial place.

Before proceeding to the proper activities related to burying the body to the ground, one of its members had to be laid to the ground, most often a finger was cut off. Some, saving themselves this ritual, threw into the urn with ashes, a handful of soil. As I mentioned at the beginning, in addition to burying, there was also body burning. On a pile made of wood, a bed with a body was set up, around which objects used by the dead were assembled, as well as incense. After a while, a relative set fire to the pile, turning his head away from the pile. At this point, weeping began again. When the fire served its purpose, the remains were quenched with water or wine. Then the relatives collected bones and ash (ossilegium), which was laid on chroma and then sprinkled with milk, fragrant oils. These activities were accompanied by the loud calling of the name of the deceased.

The collected remains were placed in a square or round urn (urn, olla or ossuaria) made of marble, decorated with herbs and honey. Such urns were sometimes provided with openings for making offerings. A completely different urn was intended for the poor. Made of pot-shaped clay without handles. Inscriptions were placed on urns. They were then taken to the grave (componere). However, over time, they were hidden in separate niches in columbaria (columbarium). Columbaria could be intended for entire families, or also slaves or freedmen of a Roman citizen. Each could contain several hundred urns. Below or above niches, appropriate epitaphia were placed.

In addition to simple urns, the Romans also used sarcophagi. They were made of clay, wood or stone (arca, capulus). During the Empire, marble became a more popular material. Initially, the sarcophagi were cuboid, decorated with garlands of flowers, leaves and fruit on the front.

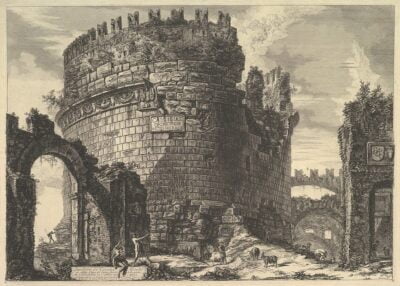

Emperors, sometimes, laid their loved ones in huge mausoleums, i.e. Hadrian’s Mausoleum, and some wealthy residents of the capital erected tombs. The graves were outside Rome, on both sides of the road. Currently, such a complex can be seen along the Via Appia.

Departing from the place of the last goodbye, participants of the procession, bid farewell to the deceased by various turns, often reminiscent of his shortcomings and weaknesses. Most often you could hear the following sentences:

- have, anima candida (goodbye flawless soul)

- molliter ossa cubent (let the bones lie comfortably)

- terra sit super ossa levis (let the earth not weigh on the bones)

- sit tibi terra levis (let the earth be light to you).

Like the Greeks, the Romans put a coin into the mouth of the deceased, which was supposed to be a fee for Charon for transporting the soul through Styx. Actors and mimes took part in Roman funerals. The first recited fragments of the tragedy, the content of which corresponded to the life of the deceased. Mime, however, in a mask resembling the face of the deceased, played scenes from his life. Masks were also put on by participants of the funeral procession.

Funeral celebrations ended with a funeral (epulae funebres). The richest at that time gave away meat (visceratio) or money donations for the poorest. Sometimes games were organized. After his death, the emperor could undergo apotheosis, thanks to which he obtained the nickname divus.

The mourning period lasted 9 days. On the ninth day, the funeral feast (cena novemdialis) took place, ending with the sacrifice of wine, oil and blood of animals (sacrificium novemdiale).

Funeral organizations

As time passed, organizations in Rome developed that helped people in financial difficulties by completing all formalities related to arranging the funeral. The establishment of such an association (collegium) required the approval of the authorities. Collegium teuiorum, as its statutory purpose, accepted the coverage of the funeral expenses of persons who belonged to that college. To accomplish these tasks, colleges have often supported wealthy people. In exchange for financial support, the colleges undertook to honor the memory of sponsors after their death. The benefit was reciprocal. A similar function was fulfilled by colleges in the Roman Army (collegia veteranorum), which were only established by retired soldiers. The main purpose of the collegium funeraticium activity was to provide a funeral service without the need to involve relatives of the deceased.

Remembering the dead

The memory of the dead was worshipped during the holidays called Parentalia falling on February 13-21, which ended with Feralia. However, the dead were not forgotten on other days. Over time, the number of days dedicated to the memory of ancestors increased. Lights were lit then, flowers were laid, and sacrificial liquids were poured.