Chapters

Third Macedonian War took place in 172-168 BCE. It led to the fall of Macedonia and the seizure of power over Greek lands by Rome.

Background of events

Despite the aid given by Philip V to the Roman legions in the fight against Antiochus III and the League of Aetolians, the Macedonian king was no longer willing to allow the Romans to disgrace his land. He slowly rebuilt his army while trying to find a valuable ally. Most often he looked towards the Thracian tribes on his northeastern border. However, for the time being, it seemed that the plan would not come into force, because in 179 BCE Philip died.

His son, Perseus, took power and turned out to be an intelligent leader. The young ruler decided to continue his father’s policy and expel the Romans from the peninsula once and for all. The young king made an alliance with the Germanic tribe, Bastarnaes, and promised to help all Greek cities. In addition, he managed to establish good contacts with the Seleucid state by marrying Seleucus IV’s daughter, Laodike. He formed an alliance with the king of Epirus and several tribes from Illyria and Thrace. He increased the size of the army and renewed economic contacts with some Greek cities.

The situation clearly disturbed the Roman Senate, which was concerned about the loss of influence in this region and the independence of Macedonia. The ruler of Pergamon, Eumenes II, who was an ally of Rome, added oil to the fire and accused Perseus of destabilizing the order in Greece. The Romans had no choice but to declare war on Macedonians in 171 BCE.

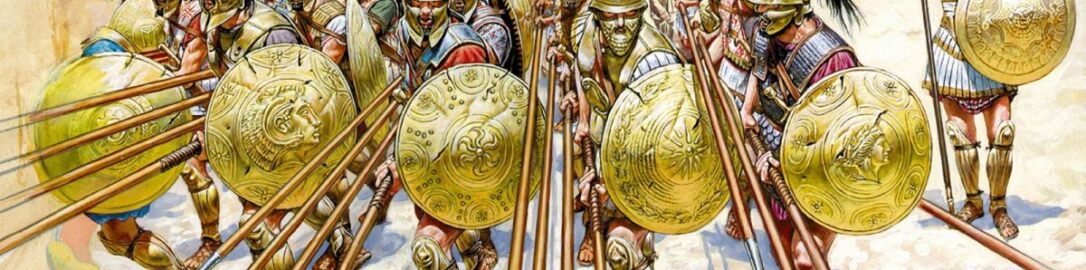

Rome, devastated after heavy fighting in the Second Punic War, the Second Macedonian War and the Seleukid War, did not have a large military reserve. The most valuable soldiers were those who took an active part in the battles with Hannibal. However, they were definitely beyond the age of military service. However, they were forced to serve the next years in the army. A number of citizen-soldiers were also recruited. Two legions, very numerous during the republic (then the legion consisted of 6,000 infantry and 300 cavalry), set out for the war, additionally supported by allies. In total, the entire army sent to the war numbered about 37,000 infantry and 2,000 cavalry. Perseus created a slightly larger army but had twice the cavalry (39,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry). The infantry was mostly filled with professional phalanxes (spearmen who were holding 6.5 meters long sarissas). It was an elite unit in Macedonia, full of tradition, but it needed level ground in order to keep the formation well.

In the spring of 171 BCE, the first Roman contingents landed on the Greek west bank of Apollonia. The transport of troops was carried out with the help of units from Carthage, Illyria and Rhodes, which emphasized the allied intentions of these countries towards Rome. The Romans were commanded by the consul Publius Licinius Crassus. With most of his troops, he began his march from Illyria towards Thessaly. Macedonian troops under Perseus waited for the Romans in the Callinicus area near Larissa. After the Romans reached this place, the Macedonian cavalry struck a completely surprised enemy. As a result of the battle (Battle of Callicinus), the Romans were defeated, losing about 3,000 people. The news of the unexpected victory of Perseus quickly spread among the Hellenes, causing the transition to the Macedonian side of other allies. The king also sent his own peace terms to Rome, which were, however, rejected. The Romans, however, could not decisively defeat the less experienced army of Perseus. In addition, there were discipline problems.

The conflict took the form of previous Macedonian wars, where both armies occupied the cities and sought small, meaningless skirmishes. Until 169 BCE none of the opponents showed greater success. The Senate, dissatisfied with the course of events in Greece, appointed a new consul for 169 BCE. Quincius Martius Philippus. Despite his 60 years, he showed great efficiency and activity. It was then that Perseus began fortifying key mountain passes, which the Roman army failed to capture. The consul gave up attacks on the fortifications, setting off on the cities of Dium and Herculaneum, which quickly capitulated. The Roman army, tired of the fast march through the mountains, decided to stop, regain strength and move the hostilities to the spring of 168 BCE.

The Senate, being outraged by such protracted fights and criticizing the current consul, decided to appoint a new commander. He was Aemilius Paulus, a respected and valued strategist. After arriving in Greece, the consul quickly began to prepare for the offensive. After a short period of preparation, the Roman army left the city of Fila and set up a camp a few kilometres from the Elpeus River, which separated the spheres of influence of both countries. The Romans tried several times to conquer the fortifications across the river but to no avail. Paulus took advantage of the knowledge of two merchants who led some of his troops through the pass and attacked Perseus from behind. The young king, frightened by the Roman troops behind his formation, fled towards Pydna. The Romans followed the king like a shadow, forcing him in a short time to a general battle, which took place in late 168 BCE. However, Paulus did not attack right away. He ordered a camp to be built, telling his soldiers to rest. On the second day, the Romans attacked, destroying the enemy. The victory was largely the result of the flexibility of the Roman tactical system. Initially, the two armies clashed and stood still fighting hard. Both commanders encouraged the soldiers by rushing to places where the situation seemed dangerous. Eventually, the Macedonian line was broken and the battle was won. Paulus conquered Macedonia, ending the Macedonian War at the same time.

Major battles of the Conflict |

171 BCE– Battle of Kallinikos

171 BCE– Battle of Pfalanna 170 BCE– Battle of Uskana 168 BCE– Battles of Skodra and Pythion 168 BCE– Battle of Pydna

|

Consequences

The Senate decided to collapse Macedonia. He divided its territory into 4 parts and then incorporated them into the republic. Administrative units established in Macedonia were obliged to pay tribute, which was, however, lower than that during the existence of Macedonia. Perseus took part in the triumphal procession, then became a slave for the rest of his life. Many members of the Macedonian aristocracy were also taken prisoner. It was the end of the Macedonian kingdom.

The enormous loot that the Romans gained during the Third Macedonian War allowed them to fill the state treasury to such an extent that in 167 BCE direct taxation of Roman citizens was abandoned.