Ancient Romans, their heritage, culture and language are considered the foundations of European civilization. As it turns out, in modern societies, one can observe extremely surprising similarities to the “sons of the She-wolf” in everyday, prosaic issues, and sometimes, unfortunately, also not very glorious. Below is a list of the 10 most interesting (in my opinion) and little-known things that do not differ much from the ancient Romans.

I. Hypocrisy in power circles

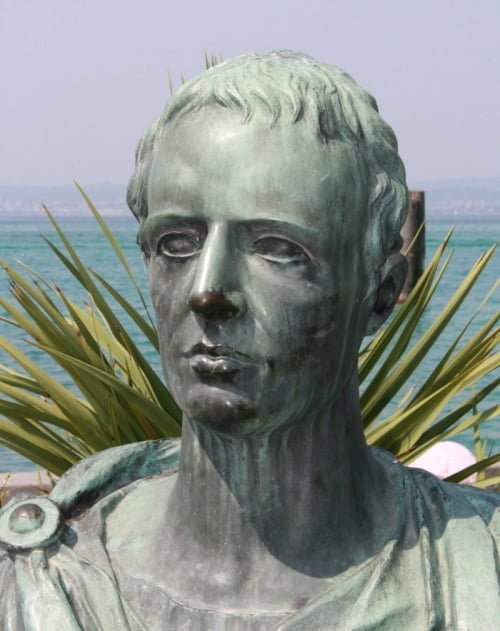

What certainly upsets many of us is human hypocrisy. There are many examples from the political scene. As it turns out, the power and politics of many people have reevaluated their lives. Going back almost two thousand years, it is worth recalling the figure of Seneca the Younger, who lived in the 1st century CE. He was a famous Roman Stoic, called the “Philosopher”, eulogist of heroic ethics, rejection wealth and anger. Many of his golden sentences have survived to our times:

- “It is not the man who has too little, but the man who craves more, that is poor”1

- “The vices of others we have before our eyes, our own are behind our backs”2

- “Man is a sacred thing for man”3

It should be noted, however, that his life, contrary to appearances, was not guided by these beautiful beliefs, especially in the later period. When he became an educator of Emperor Nero in 49 CE, he found himself in the very circle of power in the state. Seneca decided to use it scrupulously, and all crimes and crimes of Nero allowed him to accumulate a significant fortune. After the murder of Britania, son of the deceased Emperor Claudius, his fortune was divided, where his share was presumably just had Seneca.

The writer and philosopher also had numerous estates: not only in Rome but also in Egypt, Spain and southern Italy. Interestingly, his fortune was so large that he was able to grant a loan of 40 million sesterces4to new subjects – the Britons (around 60 CE the province of Britania was established); for comparison, the annual pay of a Roman legionary was about 900 sesterces. The subsequent call for debt only infuriated the Britons, who eventually sparked an uprising.

Seneca, calling for modesty and moderation in wealth, was to privately accumulate a fortune of 300 million sesterces, which mainly came from loans granted in Italy and provinces. The Roman poet Martial, irritated by the sulk and avarice of the Roman aristocracy, referred to him as Seneca praedives, meaning “Seneca the extremely rich”.

Seneca, aware that he did not follow the principles of stoicism, committed the treatise De vita beata (“On Happy Life”), in which he defended himself by claiming that living in wealth is in line with Stoic philosophy. In his opinion, wealth is neither good nor bad, but it is useful in ensuring the comfort of life. Additionally, he states that the sage is served by wealth more than poverty (paupertas), and that money can act as an instrument in attaining virtue. Interestingly, Stoicism made it clear that the most important value in life is the virtue that brings happiness; wealth, health, freedom or social status have no bearing on this. Thus, Seneca was clearly trying to save face, also proving his hypocrisy.

II. Unusual Taxes

As Benjamin Franklin said, “In this world, nothing is certain except death and taxes”. Certainly, many of us will not readily agree to this, because in order for the state to function, it needs money from the citizens. Sometimes, however, the legislator is able to come up with truly unusual taxes, including, inter alia, a tax on sweets (in Chicago) or a tax on gases excreted by cows (Estonia).

As it turns out, a similar approach was used by the ancients, who were able to reach deep into the pockets of citizens. The famous urine tax (urinae vectigal), introduced by Emperor Vespasian, made history in 74 CE. Urine was a valuable commodity in ancient times and many people collected it and then delivered it to fulling mills for a fee, which used it to whiten the material and remove stains. Vespasian, looking for new income, sensed an opportunity to provide the state treasury with additional funds. It is worth emphasizing that Vespasian – as we can guess not without reason – was referred to by the Alexandrians as Cybiosactes, from the nickname “of one of their kings who was scandalously stingy”Suetonius, Vespasian, 19" data-footid="5">5. Suetonius is referring to Seleucus VII Kybiosactes. Said nickname comes from Greek and literally refers to “dealer in square pieces of salt fish”, that is, the seller of cheap food for the poor.

Even his son Titus criticized the idea of introducing the tax. Vespasian then:

[…] held a piece of money from the first payment to his son’s nose, asking whether its odour was offensive to him. When Titus said “No,” he replied, “Yet it comes from urine.”

– Suetonius, Vespasian, 23

After Vespasian’s death in 79 CE, Titus withdrew the tax.

Interestingly, the following words have gone down in history: Pecunia non olet, meaning “money does not stink” – words that Vespasian was supposed to use as a reaction to his son’s criticism. We do not find any confirmation of them in ancient sources, and they have certainly become simply a phrase to emphasize that money can be made on any business.

III. Superstitions

Superstitions are an inseparable part of the culture and social life. To this day, many of us, when we forget something, think that we have to sit down for a while so as not to tempt fate. On the other hand, going under a ladder or shaking hands in the aisle brings bad luck.

Ancient Romans were very superstitious and believed many things that they could not logically explain. For example, an old superstition was known – kissing a female mule in the nostrils cured hiccups and runny nose. It was also thought that some people were capable of hurting others just by looking at them. Such superstition was called the “evil eye”.

The Romans believed that seeing an owl symbolized a bad omen, and smelling a cyclamen flower was supposed to prevent an evil charm. Cicero, in turn, mentions that the Romans considered it a bad omen when two oxen defecated at the same time during ploughing. Bees, in turn, considered the messengers of the gods, were lucky. Furthermore, in Rome, there was a superstition that if he talks about the wound or ulcer, do not touch the parts of the body or wearing, or the other, not at each other to download this suffering.

So as we can see, we are not much different from the Romans in terms of superstition.

IV. Texts with invectives

Criticism, as well as hatred, are something in show business that certainly drives the media and attracts readers. Often, artists are not able to be indifferent to bad opinions about themselves and react to criticism with aggression or invectives.

A great example from the Roman world is the Roman poet Gaius Valerius Catullus (c. 84 – c. 54 BCE). He belonged to a group of young poets (the so-called neoteroi) who broke with the tradition of writing historical epics and preferred small-size pieces (epigrams, epigrams, short scenes, wedding and mourning songs, small epic poems). However, a bold exit from the popular writing trend was associated with widespread criticism of his work among his most hostile authors.

Catullus couldn’t stand it one time and wrote a poem that was addressed to two critics of his work: another poet, Marcus Furius Bibaculus, and the senator, Marcus Aurelius Kota, Maksymus Messalinus. The work was so vulgar and obscene that it was not translated from Latin until the 20th century. This piece is called Carmen 16; sometimes the first line of a poem is used as the title of the work. Below is the content of the work:

I will sodomize you and face-fuck you,

cocksucker Aurelius and bottom bitch Furius,

who think, from my little verses,

because they’re a little soft, that I have no shame.

For it is right for the devoted poet to be chaste

himself, but it’s not necessary for his verses to be so.

[Verses] which then indeed have taste and charm,

If they are delicate and have no shame,

And because they can incite an itch,

And I don’t mean in boys, but in

Those hairy men who can’t move their loins.

You, because [about] my many thousands of kisses

You’ve read, you think me less of a man?

I will sodomize you and face-fuck you.

As we can see, Catullus could not keep his nerves in check and expressed his thoughts literally about his critics.

V. Attention. Bad dog!

Walking along the streets among single-family houses, it is impossible not to notice signs on the gates and fences of the property with a warning about a dangerous dog (not necessarily reflecting the realities). In this way, the owner of the house cares about his safety, secures the house against thieves and avoids liability for possible damage to the health of the burglar.

In ancient Rome, dogs were written relatively much and rather flatteringly. It was an animal ubiquitous in the culture and everyday life of the Romans and the inhabitants of the Roman Empire. They wrote about him Pliny the Elder, Cicero, Columella, Cato the Elder and many other less famous authors.

The Romans distinguished the following types of dogs: guard, hunting, luxury (peace), fighting and shepherd dogs. The guard dog should be black in colour, rather large in height, and his voice should be loud and frightening. Sharp dogs were valued here, but it was recommended to breed them that were obedient to the household and not to exaggerate the dog’s fighting spirit. Columella believed that a guard dog should scare a potential thief away with scary looks and a menacing demeanour, not real militancy. He recommended the black colour because during the day it gives the animal a deterrent appearance and makes it invisible to uninvited guests at night.

Coming back to the signs about the dangerous dog. Ancient Romans acted in a similar way. Before entering a house, Romans often placed Cave Canem (“Beware of the Dog”) on the wall, often decorated with a black animal with bristling fur and baring fangs.

There on the left as one entered…was a huge dog with a chain round its neck. It was painted on the wall and over it, in big capitals, was written: Beware of the Dog.

– Petronius, Satyricon, XXIX

In richer houses, floor mosaics were used – a great example of such a procedure is a mosaic showing a dog and the inscription Cave canem (“Beware of the dog”) at the entrance to the House of the Tragic Poet in Pompeii.

The owner of the property protected himself in this way against criminal liability for damage caused by his guardian to the clothes and body of the uninvited guest. The passerby was warned, and if he did not obey and enter the property, he was to blame himself.

VI. Pathogenic “tiny creatures”

Modern medicine is extremely developed. Our knowledge has grown significantly over the years and centuries, especially in the matter of tiny organisms, invisible to the naked eye, which is responsible for numerous diseases and unfavourable living conditions. It seems to us that bacteria were the discovery of the 17th, and in fact, 19th century when researchers saw microorganisms under microscopes.

As it turns out, in antiquity people were aware of the existence of small organisms hostile to humans. A great proof of this is the work of Marcus Terentius Varro (116 – 27 BCE) – “On Agriculture” (De Re Rustica). Varro was a true erudite, considered one of the most educated people in the history of ancient Rome.

Especial care should be taken, in locating the steading, to place it at the foot of a wooded hill, where there are broad pastures, and so as to be exposed to the most healthful winds that blow in the region. A steading facing the east has the best situation, as it has the shade in summer and the sun in winter. If you are forced to build on the bank of a river, be careful not to let the steading face the river, as it will be extremely cold in winter, and unwholesome in summer. Precautions must also be taken in the neighbourhood of swamps, both for the reasons given, and because there are bred certain minute creatures which cannot be seen by the eyes, which float in the air and enter the body through the mouth and nose and there cause serious diseases.

– Terentius Varro, De Re Rustica, 1.12

We do not know how Varro knew about it, since he himself adds that these creatures are not visible. Certainly, however, he had access to the achievements of science, which, however, were lost in the darkness of history. We also have no idea how it happened that knowledge and civilization fell so low that it took almost two thousand years for similar conclusions to be drawn after many efforts by Louis Pasteur and Joseph Lister, or even later by Alexander Fleming.

For example, the Egyptians 4,500 years ago knew the effects of penicillin; although they probably called it differently. Several sources say that lung diseases and wounds were treated with mouldy bread. Manuscripts found on papyri (eg Ebers’ Papyrus) to this day amaze scientists who agree that the knowledge contained there exceeded the knowledge of eg Hippocrates and Galen.

VII. Football fans at stadiums

Contemporary sports events, often apart from purely sports emotions, often bring aggression and clashes between fans. This type of problem, however, is not unique to the present day. Thanks to the preserved sources, we know about the clashes between ancient fans of hostile factions.

In 59 CE, in Pompeii, at the local amphitheatre, during the fight between gladiators, there were riots between the locals and fans who came from nearby Nuceria. Tacitus gives in his Annals8that it started with verbal abuse, then stones were used until finally, the crowd took their swords.

Many people died in the clashes, and many injured people returned to Rome. Interestingly, the event was so important that on the order of Emperor Nero the Roman Senate took care of the matter. The authorities in Rome banned the organization of any competitions in the Pompeian amphitheatre for a period of 10 years. However, the ban lasted only three years, as it was withdrawn in 62. All colleges and merchant organizations were dissolved, and the guilty (sponsors of the event and instigators of the brawl) were sentenced to exile.

Considering that a huge number of chariot races and gladiatorial fights were organized in the Roman Empire, there had to be more clashes of this type.

VIII. Water supply and concessions

Clean water is not unusual nowadays, especially in developed countries. Each of us turns on the faucet in the bathroom or kitchen and every day receives practically unlimited amounts of water for private use, at a relatively low price. Naturally, all water supplies are tightly regulated and pipes regularly maintained; it is not uncommon to see water supply failures due to broken pipes.

It is obvious that no ancient or later society has been able to match modern times in terms of water supply. However, ancient Rome impresses us to this day as one of the most effectively functioning state structures in the history of the world. It is no different when it comes to waterworks.

The Roman aqueduct (aquaeductus), or literally “water line”, was a water pipe supplying water from springs (most often in the mountains) to Roman cities, using the principle of continuous drainage. The water was then supplied to numerous fountains, baths and public toilets, or at wealthier homes and property. In the 2nd century CE, Rome, which had about a million inhabitants, was supplied by 11 aqueducts totalling 420 km, of which only 47 km was above the earth’s surface. This network provided one million cubic meters of spring water a day. The average citizen of Rome, however, supplied the water from fountains in public or used it in baths.

Thanks to the preserved treatises and sources, we are able to return to the times of the Empire and learn about the regulations that the Romans applied in everyday life. For example, thanks to the work “On aqueducts” by Frontinus, we know that the water supplied to the cities by water supply and aqueducts was strictly supervised, and citizens were granted a license to discharge it to their properties. Providing water for private use was associated with obtaining a concession, which was granted by the emperor through a letter. Frontinus describes step by step what the procedure for connecting to the mainline of public water supply systems looked like. Interestingly, things like the amount of water to be consumed and the size of the nozzle on the branch were regulated; this information was additionally placed in the form of a seal on the pipe to prevent fraud.

According to Frontinus in his work, the water to the thermal baths was supplied constantly and no license renewals were required; it was different in the case of private owners. In the old days of Rome, the concession did not pass from automaton to the new owner of the land or was not inherited; over time, however, the law was changed and the new landlord could continue to use the access for a fee.

Water supply conservators had to pay attention to the flow and strength of the water current, and possible defects were found especially in illegal “hooks” or “punctures”. It was common practice to “puncture” pipes, especially those located under the pavement. Leaking water, which was a “fall”, was collected, without a permit or payment, to private properties or enterprises. It is worth mentioning that the Romans even regulated the aforementioned “bleeds”, i.e. water that overflows in tanks or leaks through leaky pipes. So it was impossible to just approach the aqueduct and collect water in a bucket from a leaky structure.

Frontinus (40-103 CE), or rather Sextus Julius Frontinus, was an outstanding figure for his time. He reached the highest military (command in Germany) and political (three-time consul, governor of Britain) ranks. But surely his greatest knowledge and skill lay in engineering. During the reign of Emperor Nerva (96-98 CE) he was the curator (administrator) of Roman aqueducts. The aforementioned work “On aqueducts” (De Aqueductibus Urbis Romae), which consists of two books, is a kind of a report for the emperor on the condition of aqueducts in Rome from this period. Moreover, Frontinus presents the history and description of the water supply to the capital. It presents the laws governing water supply, the occupancy of the individual – existing at that time – nine aqueducts: Aqua Marcia, Aqua Appia, Aqua Alsietina, Aqua Tepula, Anio Vetus, Anio Novus, Aqua Virgo, Aqua Claudia and Aqua Augusta. The piece is great proof of how well organized the Roman state was.

IX. Dirty graffiti

Contemporary cities are plagued by numerous graffiti which – apart from artistic murals – disfigure the landscape and devastate buildings. Graphic designers, however, focus not only on presenting their painting “skills”, but also on delivering slogans, which often have an indecent message. Additionally, drawings of phalluses and other obscene body parts appear very often.

What’s interesting in 2013, during restoration work, on the corridor wall in the Colosseum scientists noticed a previously overlooked drawing of an erect phallus – dated in 3rd century CE It turns out that ancient fans used to draw such phalluses on the walls. Interestingly, these types of drawings were mainly intended to ensure the success of their favourites, such as gladiators. The phallus has completely lost its original meaning over the course of two millennia.

In the Greek and Roman worlds, the phallus (phallus) was widely used. The omnipresence of the phallus also meant that it was partially stripped of its sexuality. It was worn around the neck of children, it was depicted on bas-reliefs, it was decorated with lamps, jewellery and dishes, it served as an amulet, a religious symbol and a joke object. While for us an erected phallus always evokes associations with sex, in ancient Rome the range of its meanings was much wider. The phallus was a very important and lucky symbol. Some of them were additionally embellished with a lion’s paw, wings or a bird’s head.

The phallus was seen as an extremely important symbol in ancient times. Greeks, Romans and other peoples decorated, among others city walls, houses and penis baths. Among the Romans, Egyptians, Semitic Arabs, and Hebrews, it was even customary to swear by their own groin. Most often, the swearer then held his own crotch.

It should be additionally mentioned that, as today, numerous slogans were placed on the walls of ancient buildings. Scientists have discovered on the walls, among others in Pompeii and Herculaneum examples of obscene and “everyday” notes:

- Weep, you girls. My penis has given you up. Now it penetrates men’s behinds. Goodbye, wondrous femininity!

- Chie, I hope your hemorrhoids rub together so much that they hurt worse than when they ever have before!

- Theophilus, don’t perform oral sex on girls against the city wall like a dog

- Apollinaris, the doctor of the emperor Titus, defecated well here

- Restituta, take off your tunic, please, and show us your hairy privates

- I was fucking with the bartender

- Secundus likes to screw boys

As we can see, we do not differ much from our distant ancestors in terms of the need to express our beliefs or react to emotions.

X. Deforestation and Destruction of Nature

In today’s world, numerous international organizations fight to preserve unique ecosystems and protect endangered animal species. The massive deforestation, air pollution, hunting for exotic animals for commercial purposes or the expansion of human homes and cities into areas inhabited by wild animals are among the most frequently made accusations against modern civilization. As it turns out, however, we could draw patterns from ancient civilizations, among which the Romans left the greatest mark on the nature of the Mediterranean area.

Rome, along with the territorial expansion on the Apennine peninsula and beyond, led to gradual deforestation of the area it occupied. Wood for e.g. for heating or as a building material was extremely desirable. The expanding population, large-scale agriculture, and rapid economic development led to the disappearance of forests.

Grazing livestock also made a large contribution to the degradation of the environment during the Roman era. The grazing animals destroyed the woodlands to create the basis for cultivation. There were four important livestock species in the Greco-Roman world: cattle, sheep, goats, and pigs. Their combined “activity” in the selected area had a destructive impact on the environment. The pigs ate acorns, chestnuts, and beechnuts, which prevented the trees from reproducing. Sheep ate the green grass to the ground. Goats, in turn, eat everything, including bushes and young trees. In this way, farmers deliberately prevented the reforestation of the area.

The influence of Roman society on the state of the ecosystem of the Mediterranean region under the former Roman rule can be seen with the naked eye. A great example is a macchia, which is a secondary plant formation found in wetter habitats in the Mediterranean. It was established in the place of sclerophyllous, mainly oak forests, destroyed by the Romans. Hence, among others, Italy is largely a low forested area dominated by shrubs.

It should be noted that the cultivation of land resulted in the formation of wastelands and marshes. There were also natural disasters: floods (even Rome was affected by this; the first, large flood was recorded in 241 BCE), mudslides, and famines.

As you can see, even in ancient times, humanity was able to have a negative impact on the ecosystem.