Reign of Domitian (81–96) is an interesting and at the same time controversial period in the history of the Roman Empire. Writers from senatorial circles described the emperor as cruel and authoritarian.

A completely different image of this ruler is presented in the works of the court poets Stacjus and Martial, who were apologists for the emperor. Also in the literature on the subject, a negative image of Domitian and his rule was present until the mid-twentieth century. This was mainly due to the fact that the researchers relied primarily on the works of authors who were critical of Domitian. Later, historians attempted to create a more objective picture of this ruler’s rule, so they began to use other types of ancient sources. Numismatic materials have played an important role in contemporary analysis. Coins are an invaluable resource for studying ideological and propaganda aspects. Thanks to them, we are able to understand how the emperor himself wanted to be perceived by the Imperium Romanum society.

Domitian was born in Rome on October 24, 51 during the reign of Emperor Claudius. He was the youngest son of the later Emperor Vespasian and Flavia Domitilla. The Flavian family belonged to homines novi, for it was only Domitian’s father and uncle who sat in the senate. The family owed its rapid growth in importance to economic agility and profitable marriages. The climb up the social ladder also made it possible for the new families to collapse the old aristocracy, caused by years of civil wars.

During the reign of his father and brother Titus (69–81), although he was expected to be a possible heir to the throne, he played a completely secondary role in politics. It is true that he held several offices, but they were not of great importance.

After the death of his brother, Domitian without major complications began to reign as Emperor Caesar Domitianus Augustus. Already at the very beginning of his reign, he showed great military ambitions. The ideology of victory became one of the most important aspects of his rule and the basis of his aspirations for almost absolute power. In the times before the assumption of the imperial purple, his name and belonging to the ruling family must have been widely known to the society of the empire. Domitian, however, did not have the charisma, which was an indispensable element of imperial power, especially at the beginning of the princeps’ rule. In the military field, catching up with my predecessors, and above all with my father and brother, seemed necessary.

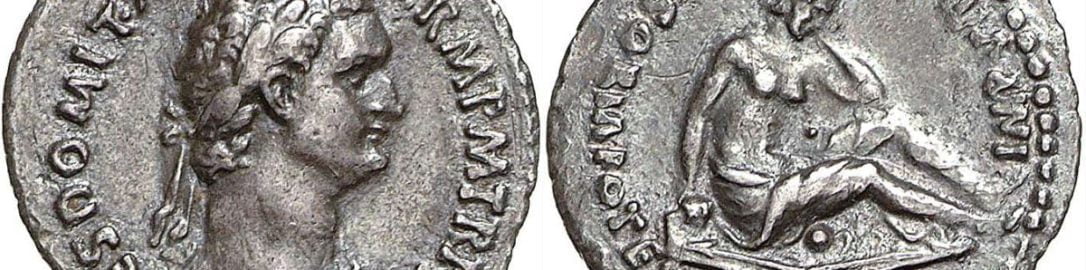

The war with the Chatti (83–85), one of the most important events in the first years of his rule, became the propaganda and ideological basis of Domitian’s rule. Unfortunately, there is little source material describing this event. The victory over the Chattas also occupied an important place in monetary propaganda, and one of its most important elements was the adoption by Domitian of the victorious nickname Germanicus.

This victory was depicted on the coins in various ways. The reverse features, among other things, the figure of the emperor himself.

The coins also showed a triumph that took place in 83 CE.

Motives referring to deities also played a very important role in monetary propaganda. Undoubtedly, the most important was the theme of Minerva, which Emperor Domitian had a special affection for. Domitian’s unique relationship to this goddess is evidenced by more types of sources than numismatic materials. It was recorded, for example, by writers of the empire. Architectural and material monuments provide further examples of the special cult of Minerva during the reign of Domitian. Among the facilities built or erected by this emperor were, for example: Atrium Minervae, Minerva Chalcidica in the Field of Mars, and the temple at the Transistorium Forum. Domitian also created a new legion – Legio I Minervia. Minerva on coins appeared in several types, but the most interesting seems to be the one showing the goddess in a fighting pose.

There is no doubt that the issuer of the coins, choosing such and not other iconographic motifs, tried to raise his prestige as a ruler. In the early days of his rule, his only legitimation of power was his belonging to the imperial family. He lacked personal charisma, thanks to which in the eyes of society, and above all the army, he could be considered a good ruler. The victorious war with the Chattas was a great legitimation of power and, along with the image of Minerva, was the main motive in coinage. Despite the fact that Domitian later waged several more wars, including with the Dacians, no motifs related to these conflicts appeared on the coins. His first war with a Germanic tribe must therefore have been extremely important to the emperor from the point of view of propaganda. The images of the deities emphasized their relationship with the emperor, and the favour of the gods was also an element of the legitimacy of power. It was thanks to their help that Domitian was to achieve his victories and maintain peace in the Empire.

The coins also show the personifications of the emperor’s personal virtues. The personification and deification of abstract concepts was an activity characteristic of the ancient mentality and religiosity. In this way, the emperor manifested his political and social program or referred to the achieved successes. On the one hand, it was possible to characterize an individual, his personality, aspirations and achievements in this way. On the other hand, the virtues could promote the continuity of the empire, its enduring values, or the ruling dynasty itself. A lot of them appear in Domitian’s coinage. The following virtutes appear on coins issued during the reign of Domitian: Virtus, Pietas, Coin, Aeternitas, Annona, Concordia, Felicitas, Fides, Fortuna, Pax, Salus, Victoria. The ones referring to Victoria and Virtus were definitely the most popular ones.

So they were personifications referring to the personal virtues of Domitian, who at all costs tried to present himself as a victorious emperor gifted with exceptional charisma.

In summary, the most important elements of the monetary propaganda of Emperor Domitian were elements referring to military victories and to individual deities. There is no doubt that the promotion of the victorious image of emperors was of great importance. It is also obvious that Domitian’s propaganda referred to the actions of his predecessors. This ruler was part of the empire’s centuries-old coinage tradition. However, it introduced some important innovations. The most unique element of his coinage was the goddess Minerva, his personal protector and the adoption of the nickname Germanicus after the war with the Germanic Chatti tribe. This war became the main propaganda base of his rule. Subsequent conflicts, most notably with the Dacians, were practically not exposed on coins. Perhaps it was considered that the outcome of these wars was not satisfactory enough. The practice of adopting the winning nicknames will be continued by his successors. Among others, Emperor Trajan accepted several of them into his title.