Otia post negotia – which in translation means to rest after work, or free time. The greatest period of development of all entertainment in ancient Rome was from the reign of Octavian Augustus and his famous room Pax Augustus (Pax Romana), who brought peace throughout Rome.

It is true that it was a peace introduced by force and it concerned internal peace (struggles with other countries and new conquests were not included in it). People, not afraid of bandit attacks or slave rebellions, could devote themselves to their activities, including entertainment to a large extent. It was the first princeps that changed the look of Rome – the Field of Mars, previously used for military exercises, turned it into an entertainment centre, built libraries, baths, porticos and rebuilt Forum Romanum1 .

Spending free time was not limited to the city of Rome. Thanks to romanization, that is, imposing Roman culture and the Latin language on the people under the rule of ancient Rome, and also succumbing to these influences, we are talking about similar pastimes throughout the empire2. This process consisted in changing the mentality of the conquered peoples and it could be said that it took place on its own, it was necessary to make people from the provinces aware that Rome is a civilization and one should strive for it. Of course, in the western provinces, it was easier. On the other hand, the eastern provinces, with a culture higher than Roman, had to reconcile and merge the old Hellenistic culture with the new one. The phenomenon of Romanization includes the promotion of Roman entertainment, it can be said that the people of the provinces themselves wanted to be “mastered” by the culture of Rome. Thus, Agricola took over Britain, not by force, but by a change of mentality. He built them baths, temples, theatres – which made people reluctant to accept the invaders’ culture, with time they wanted it themselves. In this way, the area of the entire Roman world was merged with culture, problems, language3. In order to understand well the pastimes of that time, one needs to know the various social strata. It is obvious that the people living in the village worked from dawn to dusk, and they could afford to rest very rarely or not at all. Life in the city was different – in the centre of the Empire, Rome, or much like the capital of similar provinces, such as Pompeii or Alexandria. The cities were inhabited by both the elite and the poor. The elite included patricians, the ruling aristocracy, consisting of patricians and plebeians – nobilitas, and financial aristocracy – equites. The poor were made up of plebeians who were small craftsmen and proletarians who later became customers of great families. The latter, in return for escorting and political support for their master, received material aid, invitations to events such as games or gifts – like a toga4.

My work will show how people had fun and rest in Rome. By describing the capital city, public holidays and meeting places to begin with, then the home of the rich, we will establish a pattern that most provinces aspired to. These I will deal with in the third chapter. I will show the multitude of cities close to Rome, but also the differences and traditions that were not displaced by Romanization.

Panem et circenses – public celebration in Ancient Rome

Rome is a city of opposites. In the streets, during the bustle of the day, apart from trading, you could hear poets declaring their work, slaves running with litters, but also musicians who entertained passers-by with drums, cymbals and flutes5. It was crowded in the capital, next to the villas there were insulae, or multi-story tenement houses inhabited by poultry craftsmen, traders and customers6. The time to celebrate was when the inhabitants were not burdened with work or basic necessities. At that time, both the elite, workers who were able to find about 17 hours off each day7, as well as clients could take care of the rest provided by the emperor and crowds of officials.

The rulers, wanting to gain the approval of the people, organized new holidays, the so-called Ludi, or extended the already existing8. From the morning you could watch horse racing in Circus Maximus, gladiator battles in Colosseum, performances of mimes in the theatre. As many as 128 days of celebration in Rome was obligatory, not counting of course non-obligatory days, which were, for example, district festivals, assembly feasts or feasts in honour of less important gods (e.g. Attis). During the empire, when it was still necessary to celebrate the date of the king’s accession to the throne, there were one or two public days for one working day9. Most of the Roman pastimes came from more extensive religious rituals. An example is the gladiatorial fights fought originally by prisoners of war on the tomb of the victorious commander, as an offering to the gods. Over time, however, they became very popular among the citizens of Rome.

Roman plebs enjoyed many privileges, at first, the bread for them was sold for pennies, then it went to give away. In addition to state bread, customers could always count on material help from their master. The first most recognizable entertainment structure in Rome is the Colosseum. Built in the times of the Flavians, it was a three-story building with a capacity of approx. 45 thousand. viewers, the sheer size tells us how much the Romans liked to celebrate10. In the times of the emperors, the games became more and more brutal, and crowds could watch fights, fights between humans and animals, hunts, fights between animals, and even naumachie, or sea battles in a flooded amphitheatre11 . Gladiators are slaves or prisoners of war trained in the so-called school of gladiators, where they taught them to fight with various types of weapons12. The Romans were bored of seeing the same animals, panthers or elephants writing the emperor’s name on the sand. Therefore, the emperor, in order for the plebs to be pleased, sent his people to the provinces of, for example, Africa to catch valuable animals there: bears, buffaloes, bulls, rhinoceros, aurochs, bison, hippos13. Another entertainment, most harmful in the opinion of modern man, was tearing people apart by wild animals, the most popular example here is the punishment of Christians accused of setting fire to Rome in 64 CE in the time of Nero, but this is not the only example. After the unsuccessful uprising, Jews also died entertaining crowds in the Roman amphitheatre. To make the show more interesting, myths were recreated using convicts, such as the myth about Prometheus14. (what a machine it is – pleases, condemns, keeps it in order!).

Circus Maximus was attended earlier than the Colosseum. The most popular competitions were races of four stables marked with four colours: red, white, green and blue, but the last two really counted15. It was here that gambling took place, on which adults often lost all their fortune. The crowd in the audience could not be bored, the riders could show off by jumping from horse to horse, and there were also chariot races (4 to 9 horses harnessed in them). In Circus Maximus, the Romans could also watch numerous infantry and cavalry performances. After many hours of the struggle of the players and the excitement of the crowd, the emperor often staged feasts at which he handed out gifts, which was especially liked by the losers in the bets16.

In the time of Nero, there was a celebration taken from the Egyptians, consisting in worshipping the god Serapis, drinking good wine in the previously built taverns and garden pavilions, and the aristocracy’s performances on stage – as actors, which was previously associated with disgrace. The emperor for whom this holiday was organized could have acted this way17. Already before the 3rd century BCE, the Roman people were content with the performances of Etruscan actors to the accompaniment of instruments.

The theatre began to develop as Greek plays were translated into Latin and accepted by the Roman audience. The Romans were afraid that their culture would be dominated by Hellenic culture, so it was only Pompey who managed to build a permanent theatre, but the people of the big city, often crude, were bored with the long Greek plays full of dialogue18. So the dialogues were shortened or turned into sung parts, and the eyes were delighted with the dance elements. She also made fun of the so-called atellana, a kind of Roman comedy in which the characters were so exaggerated that seeing a stupid old man or a glutton, the whole audience would burst out laughing. The Romans also made their own celebrities, they were mimes who, contrary to the present day, were very talkative actors, singing light songs, dancing or, in the case of women-actresses, undressing on request. They performed solo and without masks so that everyone could admire and recognize them. The tragedy, which is the least popular because of its difficult subject matter, turned into a more accessible and more eagerly watched pantomimic dance (the actor played successive characters of the tragedy with his dance)19.

Roman theater also hid its sensations, actors from the stage were able to attack people known all over Rome, pursue a policy opposite to the authorities, which certainly excited the audience. About such a demonstration against Pompey writes Cicero20. The themes of the performances appeared differently, at the beginning they were historical scenes or myths, then they talked about everyday life, including, for example, the work of courtesans, which, when shown on stage, made the audience laugh and interested the audience, but it was everyday life for them21. The Roman scene did not contain high-class literature, and young writers – gifted or not – could not stand out. They had the opportunity to show up in the crowded Roman streets. By reading their works, they either gained the approval of the audience or were simply ridiculed. The richer ones built special rooms in their homes – auditorium, where they preached often boring speeches in front of their friends. It became so popular that even funeral speeches could be heard in the streets, and the performers in the auditorium changed roles (performer – listener). Thanks to this everyday entertainment, the level of literature and recognition of who could be a poet have dropped significantly22.

From the time of Emperor Augustus, citizens could enjoy public libraries where they read Greek and Roman literature, and overtime in Rome we can find as many as 28 public libraries23. There were open taverns on a daily basis – the equivalent of today’s taverns, attended most often by commoners. There was a place to talk about work and rest, as well as a popular game of dice, often for money24. Gambling in Rome was so popular that it was banned. There were special days when it could be done legally, but it was in the tavern where the law was broken most often. Every day people met, shopped, ran their errands or even went to the temple at the Forum Romanum. This place played the role of the Greek agora, when the city was getting bigger, new forums were created25. Another meeting place was the porticoes, which were built in Rome during the reign of Augustus on a massive scale. They served as an open-air museum today, you could walk among the works of the most outstanding artists, there were often libraries, and sometimes fountains. Children play very similar games to adults – these are numerous games with a ball (apples and chestnuts were also used instead of a ball), a game resembling today’s croquet and rolling hoops26. In addition, they played in wars, first recreating those with Carthage, then the battle of Actium.

The basic association with leisure time among the Romans, apart from the games, are baths. Spending time in the baths was very attractive, which is why there were as many as a thousand of them in Rome. Immediately after arriving at the bathhouse, citizens devoted themselves to gymnastic exercises and games, which were most often associated with the ball, they were, among others, the “triangle” game in which the players lined up in a triangle received the ball with one hand and rejected it with the other. Throwing a heavy ball stuffed with sand or a light ball filled with air was also popular. You could also prove yourself in wrestling or playing similar to today’s fencing. This warm-up was followed by a bath, it consisted of three stages that were always followed. First, a dry bath, comparable to today’s sauna, then a bath in hot water, and then in cold water. Time after bathing could be spent in a variety of ways, going to the library, promenade, engaging in conversation, watching the players or listening to poets reciting. Interestingly, both men and women went to them, first together, and during the reign of Hadrian, separate hours of use were designated. Unfortunately, this free (from the times of Augustus) entertainment did not last 24 hours, the thermal baths were closed at dusk27.

The thermal spa sport differed from that in Ancient Greece. The Romans were reluctant to public nudity. During the republic, Marcus Fluwius Nobilior organized games following the Greek pattern, enriched with, among others, animal fights, but they did not catch on. He wanted to come back to this Julius Caesar, he combined traditional Greek competitions with Roman gladiatorial fights, but in fact, Emperor Nero began to learn about Hellenistic culture in depth. Enchanted with his musical and acting talent, he himself went to Greece, where he won many victories, and returned to Rome like a triumphant, without bringing Greek passion in society behind him. Greek sport in the capital of Imperium Romanum actually appeared in the times of Domitian. He built the stadium on the Field of Mars (previously there were numerous porticoes) and the concert hall. Residents attended the Capitoline Games established by him, and after his death, the stadium began to be used for gladiatorial fights, or it was flooded with water and watched at staged battles of ships28. This proves that the Romans readily embraced the Hellenic culture, but only if it suited their habits and provided pleasure. They were used to their way of life, what they learned, they did not want to change, they could only diversify it.

Entertainment at home

Wealthy Romans spent their time in their private libraries, in villas, often located outside the capital of the empire. The basic works that every valued citizen had to know were the works of Virgil, Horace, Ovid, Statius, Terentius, Sallustius, Cicero and Livy29. In the first century BCE, many Italian publications already existed, but also Greek books written on papyrus were imported, which filled spacious, private libraries30. Cicero, wanting to devote himself to literary studies, also used the libraries of his neighbour – Faust Sulla. He wrote that reading was his consolation in difficult moments31. For many, it was a place of relaxation and meeting a diverse culture. Private concerts of the game, eg on the kitra, entertainment inaccessible to the masses, were highly appreciated by the aristocracy32. The edicts issued by aediles on the prohibition of keeping wild animals such as bears, dogs, panthers and lions are about the rich people’s love of the exotic in their immediate vicinity. Farms of peacocks, quails and fish, which were then eaten, were also popular33. Wealthy Romans cared for the personal as well as the home appearance. Cicero, who, despite his debts, bought more villas, wrote to his friends about the desire to decorate them with valuable works of art34. The aristocracy spent a lot of time taking care of its body before going out on the street, meeting or attending a show. Women wore curls on their heads most often, the hairstyle that lasted the longest is the so-called “bee’s nest” or diadem.35

The most important meal for every Roman was dinner, consisting of hot dishes, poultry, fish, desserts. There was wine to drink, but they didn’t drink much while eating, only after all meals were served. They were eaten lying down and with a large group of friends, some even asked for invitations, and they were not only poor people or poor artists but also rich people who wanted to show themselves. The feast begins between 1 p.m. and 3 p.m., after visiting the thermal baths. At this point it should be noted that their day began much earlier than ours because they got up before sunrise, even the richest36. It was good to bring your slaves to huge feasts, preferably more than one if only to guard the shoes, which had to be removed before getting on the bed, and which were often stolen. In the meantime, you could listen to music or watch the dancers. They were slaves trained in special centres, they could not only dance and entertain with the conversation but also often play the lyre, flute, sing and recite37. The host made the time more pleasant with a lottery, where you could randomly choose from a few dates to your own slaves. It is also not allowed to generalize, for some residents of the capital, it was a modest meal, not lasting until dawn, only 3-4 hours as standard. Often it was educated and cultured people who dined with their closest friends, amid calm and intelligent conversations. We also have a very exaggerated image of love, and we even think that love in ancient Rome was based on orgies. They were most common among emperors or very wealthy citizens, and those described by Seneca and Pretorius entered the basic associations38.

Roses and free time in the provinces

Thanks to romanization and Pax Romana, entertainment from ancient Rome flourished. Many people moved to cities, the causes of this phenomenon were, among others, civil rights gradually granted to free people from the provinces by emperors. The culmination of this process was Caracalla in 212 constitutio Antoniniana. Many cities founded at the beginning of our era have survived to this day, often as capitals of great states: incl. Lutetia Parisiorum (Paris), Vindobona (Vienna), Aquincum (Budapest)39. The structure of the city resembled Rome, so there were: thermal baths, theatres and amphitheatres. The latter was not only in the cities of Italia, such as Pompeii or Verona, they were also in distant Gaul, such as Nimes, Arles. Theatres in Libya (in Sabratha) or in today’s Turkey (in Aspendos)40. Spain and Gaul were the quickest to adopt Roman culture because this culture did not compete with others, just like in the east41. Just like in Rome, thanks to the distribution of grain, people did not have to worry about hunger, so entertainment spread42. Many holidays were established in the era of the empire because there was the so-called “cult of emperors”. He was the reason why, for example, the games were established in Achaia, gladiator shows were organized in others, and hymns of praise were recited43. Gladiator fights are very common in the provinces.

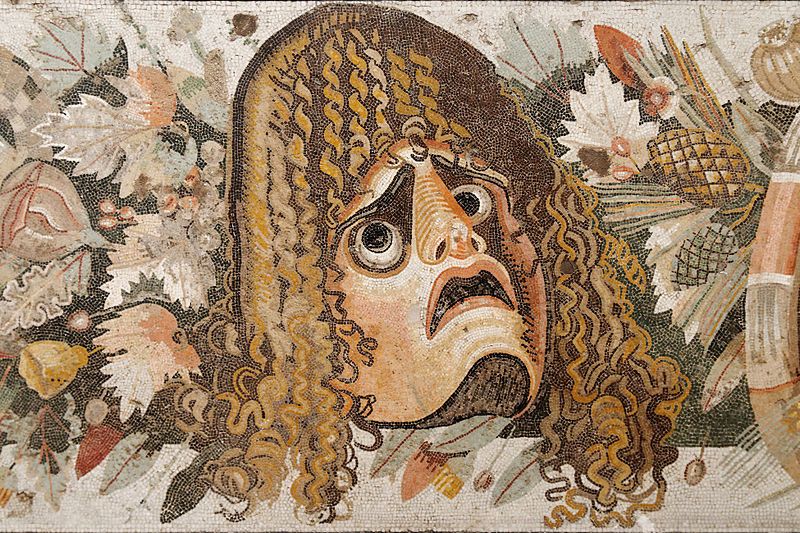

Already in the 2nd century BCE, it was introduced to his court by the Syrian king – Antiochus. In later times, gladiators’ schools were also, inter alia, in Capua, Praeneste (present-day Palestine) or Pompeii.44In Africa, the torments of Christians were popular, often for the greater joy of the crowd – as in Rome, bloody mythological scenes were played there, sometimes that it was accompanied by an orchestra. People loved the entertainment, as is evidenced by the mosaics and dishes decorated with scenes from the amphitheatre45. A philosophy transformed into the Roman model flourished in Athens, while Cicero, while there, recalled philosophical lectures taking place in the amphitheatre. Undoubtedly, both these lectures and those held in the gymnasium were entertainment for the people of that time46.

Each provincial city wanted to be a representation of Rome. Thanks to the sewage system, the aristocracy could rest in the thermal baths for several hours a day, in addition, theatres and amphitheatres were often built, which could sometimes be compared to the Colosseum. To this day, we can admire them in Gaul (in Nemausus, Arelate, Autun)47. Interestingly, in the area of Imperium Romanum, people did not live only according to the Roman scheme, because although the capital did not accept the Olympic Games in the Greek style, in most provinces it was an indicator of belonging to the empire. Apart from the “saints” Olympics, ie those after which the winner gained fame, there were also smaller or completely recreational sports competitions that enjoyed the eye and body48. Public libraries also caught on in the provinces, they were built in the Roman style, that is, divided into two rooms with Latin and Greek literature. They were often founded by the rich and named after them, e.g. the Celsus Library in Ephesus, Hadrian built a special room in Athens and even in Africa, in Timgad we can find a special building49.

One of the ideal examples of cities in the Roman Empire is Pompeii, a wealthy city where many feasts were found, and gardens were found next to each house. The richer ones housed a fountain and sometimes a vineyard. Pompeians often spent their time relaxing. There were separate baths for men and women in the city, and the wealthier ones had bathhouses in their homes. The theatre and the amphitheatre were also obligatory entertainment. The audience was so excited about the performances that there were fights there. Gladiators came from a school in Capua50. In the provinces, the aristocracy was not less educated, as evidenced by the library discovered in 1752 in one of the Pompeii villas, which contained outstanding works of that era51.

Far Africa has not been forgotten at all, examples of the development of this province are the three cities of Leptis Magna, Sabratha and Thysdrus (today’s Al-Jamm in Tunisia). In the first one, there is a palester – a place for exercises, right next to Hadrian’s baths. Visitors could see the wonderful works of art that are now housed in the museum in Tripoli. There was also a theatre in the city, most probably funded by a city clerk. At the seaside, right next to Leptis Magna there was an amphitheatre with a capacity of several thousand spectators, built during the times of Nero. There was also a circus, where 12 chariots could race at once52. Sabratha, in addition to standard entertainment facilities, boasted a unique theatre that could accommodate 5,000 people viewers, and the wall to be decorated was 25 meters high53. African villas were larger than the Roman ones but did not have an atrium. The rich rested in home gardens with numerous fountains and pools54. Alexandria, despite the stadium, amphitheatre and hippodrome, did not gain much from the Roman appearance, traditional Egyptian entertainment was still the most popular there55. Jews, apart from their traditional games (e.g. spinning tops, dice, lottery games, a game similar to our checkers, a circle game, wrestling, target shots, slingshots, ball games), took over some entertainment from the Greeks and Romans. They gladly went to the thermal baths or gymnasiums that were sometimes adjacent to the synagogue, such as in Sardis. Herod, on the other hand, spread the Greek Olympic Games, built a hippodrome, and possibly the amphitheatre in Jericho. But not only was it possible to get entertainment there, but the facilities were also, among others, in Caesarea, Tarychea, Samaria – Sebaste. Bloody gladiatorial fights, public punishments, were contrary to Judaism, so they were not practised. Only those during which no blood was shed were allowed, although the rabbis protested because they were still pagan pastimes56. There were also soldiers from the entire empire in the provinces, their entertainment is also worth mentioning. Bathhouses were a typical feature, as no Roman citizen could imagine life without them. Units built in places of stationing, e.g. in Chester, were usually not worse than those in the city. Tacitus also reminded the soldiers of their voracity, we know only from private letters to families that the fighters did not complain about the lack of delicatessen from all over the world, eg asparagus, poultry or oysters57.

Termination

A large amount and variety of entertainment in the Roman world is little known today, so it can be strictly assessed. However, it is worth taking a critical look at today’s world. We also gamble in arcades, we go to pubs like Romans to taverns. We are happy to watch the performances of infantry and cavalry, as well as artillery as a show of strength and power of the state. We enjoy the broadly understood theatre, we have our celebrities, mime dances have replaced ballet, we listen to operas, operettas, we watch comedies and dramas. Exaggerated characters from Roman comedy are replaced by serial heroes, such as Ferdynand Kiepski or the gentlemen from the bench in the series “Ranch”. We have access to libraries, we debate and listen to public readings. We have replaced private concerts with music from the radio or CDs, but we have not given up on live music – concerts take place in clubs, open-air or at the philharmonic hall. We live too fast to have time every day for at least a few hours’ meals with family, not to mention friends. Once upon a time, people hired for companionship were pleasant, also today in the richest countries (USA, Japan) this custom is cultivated.

It is clear that the Olympic Games have survived almost unchanged and strongly refer to antiquity, but the thermal baths did not find a direct continuation. We can talk about swimming pools, often connected to gyms, but numerous games in the yard, walks, discussions do not take place in the same place as the baths. Adults rarely know how to play anymore, but the form itself has not changed at all – today we have checkers, ball games, throwing dice, in poorer countries children roll wheels and play war. The Romans bred various animals, today we are usually accompanied by dogs, cats and rodents, and we can see the exotic at the zoo. The meeting place, the former Forum Romanum, can today be shopping malls or city centres. The most difficult to spot in our time is the brutal entertainment that took place in antiquity in Circus Maximus or the Colosseum. Horse racing, once so popular, today has gained a more sporting status. Sea battles have become popular – they are simply historical reenactments watched by thousands of people. Animal fights have survived to this day, although it is forbidden, only animals were changed, in the arena instead of elephants, panthers, rhinoceros, we can see roosters and dogs. Trained animals, such as elephants and lions, can be seen in circuses.

Finally, it is worth asking, “Have we got rid of the bloodlust that the ancient Romans no doubt had?” In addition to human rights, the prohibition of the death penalty, and the use of violence, there are bloody films, documentaries and series. We can explain that no one gets hurt, but we look with the same excitement at death, suffering and pain. Television takes us to the arena, we can be as close to death as we are in the Roman world, and we are.