Chapters

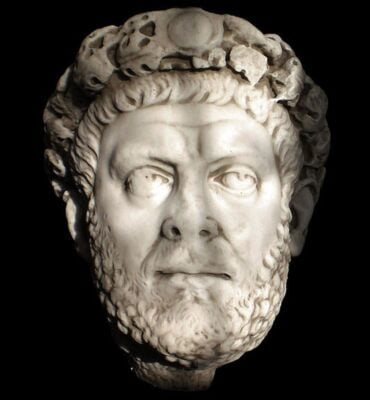

| Names | Gaius Valerius Diocles |

|---|---|

| Ruled as | Imperator Caesar Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus Augustus |

| Reign | 20 November 284 – 1 May 305 CE |

| Born | 22 December 244 CE |

| Died | 3 December 311 CE |

Diocletian was born probably around 244 CE in Solina (Salona, now Croatia) as Gaius Valerius Diocles. His reign begins the period in Rome which we call dominate. It was basically an absolute monarchy based on an army and centralized bureaucracy. Diocletian completely gave up the apparent behavior of the republic under the principate.

Youth

According to contemporary historian Timothy Barnes, the exact date of Diocletian’s birth is December 22, 244 CE. Other historians, however, are skeptical about this claim.

Diocletian’s parents used to call him Diocles or Diocles Valerius. His parents were of low status, and Roman historians critical of Diocletian claimed that his father was a scribe or freedman of senator Anullinus. Diocletian was also said to have been a freedman himself. The Byzantine chronicler Ioannes Zonaras claimed that Diocletian was Dux Moesiae, commander in chief of the Lower Danube troops. Considered incredible – Historia Augusta mentions that Diocletian served in Gaul, which is however not confirmed by other sources and is rejected by modern historians. Much of Diocletian’s early life is unknown and remains a matter of guesswork. It is certain that Diocletian, in order to break out of a low position, had to seek the development of his career in the military.

Coming to power

When Emperor Carus died in the summer of CE 283, the unpopular sons Numerian and Carinus took his place. Carinus, upon the news of his father’s death, immediately went to Rome to strengthen his power, where he appeared in January 284 CE. His brother Numerian, fighting in the east with the Sassanid king Bahram II, first had to calm the situation in the troubled region. Unexpectedly, during the trip to Bithynia, the soldiers discovered that Emperor Numerian was dead, and his body had already been affected by a decay process in a litter covered with sand. The cause of his death is unknown. It was known that the emperor contracted eye inflammation in a desert region, which, however, could not be fatal.

Regardless of the circumstances, however, in November the soldiers and the command ordered the convening of a military council, which appointed Diocletian to succeed Numerian, despite his efforts to become the official of Numerian, Lucius Flavius Aper. On November 20, 284 CE the army in the east gathered on a hill 5 kilometers from Nicomedia (Asia Minor). The soldiers swore allegiance to New August and offered the purple which Diocletian accepted. The new ruler then raised his sword towards the sun and made a promise that he had nothing to do with Numerian’s death. He accused Aper of this deed, which he then personally killed in front of the legions. Immediately after Aper’s death, Diocletian changed his surname Diocles to the more Latin-sounding Diocletianus. Eventually his full name was Gaius Aurelius Valerius Diocletianus.

Competition with Carinus

Upon assuming office, Diocletian appointed himself and Lucius Caesonius Bassus consuls, and made himself fasces. Thus Diocletian distanced himself from Numerian and Carinus. Bassus himself was a member of the Campanian senatorial family, a former consul and proconsul of Africa. He had abilities in the area of administration that Diocletian probably did not have. The very election of Bassus as consul was certainly symbolic and meant that Diocletian did not recognize Carinus’ sovereignty and rule. The support of Bassus was necessary for Diocletian, certainly also in the face of his trip to Rome, where extensive contacts with the Roman aristocracy were necessary. Bassus certainly had such connections.

Diocletian was not the only opponent of Carinus. He was opposed by Julian Sabinus, also known as Julian of Pannonia, who took control of northern Italy and Pannonia upon the news of the acclamation of Diocletian’s candidacy by the eastern legions. Julian minted coins with his likeness in Siscia (Sisak, Croatia) claiming to be the emperor and promising freedom from the rule of Carinus. All these events put the full ruler and heir in a bad light. To this end, Carinus brought numerous troops from Gaul, Spain, and Britain to deal with the militarily weak Julian and Diocletian, who posed a greater threat. In early 285 CE, Carinus defeated the usurper Julian Sabinus in a heavy campaign, supported by the Praetorian Guard. In the winter of 284-285 CE, Diocletian at the head of his army crossed the Balkans. Diocletian fought several skirmishes with Carinus’ forces, which retreated to Sirmum. Around July 285 CE he met Carinus’ troops on the Margus River (Great Moravia) in Moesia (the Battle of the Morava River Valley).

Despite his superiority in numbers, Carinus was in a worse position. The general aversion that prevailed towards the person of the ruler grew stronger. The beginning of the battle belonged to Carinus, whose troops gained the upper hand. However, the emperor was not allowed to win, because during the battle he was murdered by conspirators from his command (whom Carinus, famous for his promiscuity, allegedly seduced his wives). The death of Carinus finally ended the civil war. Diocletian took the oath of Carinus’ soldiers and went to Italy to consolidate his power.

Reign

It is possible that immediately after the battle in the Morava River valley, Diocletian had to fight with the Quadi and the Marcomanni. Regardless of the circumstances, however, the victorious emperor finally went to Italy (we do not know if he was in Rome at that time). We have coins minted on the occasion of the emperor’s entry into the capital (adventus), but most historians believe that Diocletian avoided visiting the city, which he felt was unnecessary. The emperor did not need official ratification of his office. Diocletian counted his reign from the moment he was announced as August by soldiers in the east, and, like Carus, saw the Senate resolutions as meaningless rites. Even if the emperor appeared in Rome, it was a rather short visit, because on November 2, 285 CE, he had to conduct a campaign against the Sarmatians.

Diocletian changed the post of praefectus urbi to his friend Bassus. Apart from this change and a few minor ones, most of the offices remained in the hands of officials of the rule of Carinus. Aurelius Victor, a 4th-century Roman historian, mentions that Diocletian, contrary to common rules, showed clementia (grace) and did not kill the praetorian prefect and consul Tiberius Claudius Aurelius Aristobulus who betrayed Carinus. Interestingly, he kept him in position, which was an exceptional situation. In addition, in time Diocletian made him proconsul in Africa and city prefect. Probably the rest of the people who betrayed Carinus also kept their positions.

Power sharing

Diocletian realized that sovereignty in the Roman Empire, a country that spreads over vast territories, was an inadequate system of government. Sooner or later, there is a usurper and a civil war, with which, for example, Probus or Aurelian have to deal with. Conflicts occurred in remote corners of the Empire: Gaul, Egypt, Syria, the lower Danube. To this end, Diocletian decided to appoint a sort of associate/deputy to help him run the country. In 285 CE at Milanum, Italy, he appointed as a Caesar certain Maximian, officially co-regent, but in the practice of a lower rank.

The concept of dual rule was nothing new in the Roman Empire. Diocletian was in such a dire situation that he did not have a son, but only a daughter – Valeria. Consequently, he could not base his power on a certain and faithful family member, but a person outside the family. Some historians claim that Diocletian adopted Maximian as filius Augusti (“son of Augustus”), which was a precedent among emperors. Until now, all dual power was present in the family, because the degree of fidelity of the co-emperor was feared. However, the issue of Maximian’s adoption is not 100% certain.

Diocletian’s relationship with Maximinus was religiously established around 287 CE, when August became Iovius and Maximian Herculius, which emphasized the importance of both rulers. Such a title could result from the assumption of Roman statehood as seen by Diocletian. He himself, like Jupiter, was to be the manager and planner, and Maximian, as his Hercules and son, would obey the tasks. Both were not considered purely as gods, but merely as their representatives who exercised divine judgments. Diocletian was to rule the East and Maximian to control the situation in the West.

Fighting the Sarmatians and Persians

After the acclamation, Maximine traveled to Gaul in order to suppress the Bagaudian revolt. Diocletian, in turn, decided to slowly return to the east. In the Balkans in the fall of CE 285, he encountered the army of the Sarmatian tribe, which demanded his help in regaining the lost lands or permission to graze animals in Roman territories. The emperor refused and fought a battle with them, which did not bring complete victory. It is worth adding that the pressure of the Sarmatians resulted from the displacement of tribes in Central Europe. The Nomads’ pressure on the tribes inhabiting Central and Eastern Europe was too big and widespread a phenomenon to be able to settle the conflict in one war. Diocletian had to prepare for the next clashes with the Sarmatians.

Diocletian spent the winter of 285/286 CE in Nicomedia. At that time, there was probably a revolt in Asia Minor, as a result of which the ruler ordered the resettlement of some of the region’s inhabitants to Thrace, where they were to take care of the abandoned agricultural lands. Diocletian then traveled to Syria Palaestina in the spring of CE 286 to win a diplomatic victory during that time. The ruler of Persia, Bahram II, with whom Rome had so far had a hard time, decided to gain Diocletian’s friendship with great treasures. In addition, he officially invited Diocletian to his court. Roman sources mention that it was a completely independent act of goodwill on the part of the Persians.

At the same time, Persia renounced its claims to Armenia and recognized Roman rights to the territories west and south of the Tigris. The western tracts of Armenia’s lands were incorporated into Rome. The Armenian king, Tiridates III became the puppet ruler of Rome. Rome’s unexpected peace with Persia was considered a great victory for Diocletian, who was considered a “creator of eternal peace”. The emperor also reorganized the eastern borders (especially in Mesopotamia) and strengthened Circesium (Buseire, Syria) on the Euphrates.

Maximian became Augustus

Maximian’s actions in the north were not as smooth as those of his more important partner. Despite the swift victory over the Bagaudians, a certain Carausius stepped out against the legitimate rulers unexpectedly. During Maximian’s actions, he was building a fleet to fight against sea pirates marching off the coast of Gaul and Britain. He used his position for private purposes (spoils taken from pirates), he escaped from arrest to Britain, where he proclaimed himself a Roman emperor at the turn of 286 and 287 CE. Maximian, realizing that it would not be easy for him to defeat the self-proclaimed behind Ryn. In the spring of 288 CE, Maximian prepared a fleet against Karauzjus (he was later murdered by Allectus, another usurper in 293 CE). Unexpectedly, however, Diocletian returned to Europe from the east. They decided to attack the Alamans together: Diocletian was about to strike through Retia, when Maximian was about to march out of the present Mainz. Each army on the march collected loot and burned Germanic lands. The victorious campaign allowed the Empire to expand. Diocletian agreed to the attack against Karausius as he himself headed back east to suppress another Sarmatian rebellion. We have some inscriptions saying that after CE 289 Diocletian assumed the title Sarmaticus Maximus.

In the east, Diocletian continued his diplomatic efforts, this time with the desert tribes located between Rome and Persia. Attempts were made to make an alliance with them and renew the old peace treaties, or simply limit the invasions of Roman territories.

Meanwhile, in the west, Maximian lost his fleet, built at the turn of 288/289 CE, in the early spring of 290 CE. The cause of the loss of ships could have been a strong storm or simply the commanding ineffectiveness of the Roman admirals. Diocletian, in turn, withdrew from the survey of the eastern provinces and traveled west again, reaching Emesa on May 10, 290 CE and Sirmium on the Danube on July 1, 290 CE.

Diocletian met Maximian in Mediolanum in the winter of 290/291 CE. The meeting was very pathetic and ceremonial. Both held numerous public audiences to underline Diocletian’s continued support for Maximian, despite some military defeats. The choice of a place to meet the two most important people in the country was also not accidental. Mediolanum was gradually created as the second capital of the Empire. Rome was still, of course, but more ceremonially. Mediolanum was more centrally located in relation to the entire territory and staying in this city allowed for a faster reaction in emergency situations at the borders. Already Emperor Galien (ruling 253-268 CE) chose the current Milan as his seat. Importantly, as Herodian mentions, the thesis was already taking shape at that time: “Where is the emperor, there is Rome”.

During the Milan meeting, talks about politics and wars were held in secret, and the rulers were not to meet until CE 303.

Tetrarchy

Before CE 293, Diocletian decided to entrust the command of the fight against Carausius to Flavius Constantius (later Constantius I Chlorus), a former Dalmatian governor and military officer who had reached the reign of Emperor Aurelian with his service. Flavius took part in the war against Zenobia (272-273 CE). In addition, Constantius was the prefect of Maximian’s praetorians in Gaul and the husband of his daughter, Theodora. On March 1, 293 CE, Maximian bestowed the title of Caesar on Constantius. In the spring of the same year, either in Philippopolis (Plovdiv, Bulgaria) or in Sirmium, Diocletian undertook a similar action against Galerius, the husband of his daughter Valeria, and possibly his praetorian prefect. Constantius was in charge of Gaul and Britain when Galerius took over Syria, Palestine, Egypt, and the frontier areas of the East.

This agreement and division of power in the Roman Empire was called tetrarchy, which in Greek means “rule of four”. The tetrarchy did not formally divide the territory of the empire between the rulers, each of them was the emperor of the entire empire, but the tasks assigned to them concerning specific areas:

- Diocletian, Augustus of the East, controlled the lands of Asia and Egypt, his capital was Nikomedia;

- Galerius, Caesar of the East, controlled the Danube area, mainly from Sirmium on the Sava;

- Maximian, Augustus of the West, dealt with the affairs of Italy, Africa and Spain, first from Aquileia and then from Milan;

- Constantius, Caesar of the West, looked after Gaul and Britain from the capital of Trier.

Another change introduced by Diocletian was to limit the duration of the Augustinian rule to 20 years, after which they were to abdicate in favor of their Caesars, and they, in turn, should appoint new Caesars – their future successors.

Fighting in the Balkans and Egypt

Diocletian spent the spring of 293 CE traveling with Galerius from Sirmium (Sremska Mitrovica, Serbia) to Byzantium. He then returned to Sirmium himself, where he stayed until the following spring. He led the victorious campaign again against the Sarmatians probably in the fall of 294 CE. The defeat kept the tribe away from the Danube for a time. During this time, Diocletian built new forts north of the Danube: Aquincum (Budapest, Hungary), Bononia (Vidin, Bulgaria), Ulcisia Vetera, Castra Florentium, Intercisa (Dunaújváros, Hungary), and Onagrinum (Begeč, Serbia). The forts were included in the new Ripa Sarmatica defensive line.

In 295 and 296 CE Diocletian led another campaign in the region and won over the Carpathians in the summer of 296 CE.

In the period from 299 to 302 CE Diocletian was in the East, and at that time Galerius took his place on the Danube. By the end of his reign, Diocletian strengthened the border on the Danube, providing new forts, passages and city fortifications. In addition, a dozen or so legions patrolled the region to secure the “underbelly” of the Empire.

Galerius, in turn, in the years 291-293 suppressed the uprising in Upper Egypt, which was a consequence of Diocletian’s tax policy. Augustus wanted to align the tax in Egypt with the Roman standard. In connection with the ruler’s plans, a rebellion was raised by Domitius Domitian, who proclaimed himself emperor in July or August 297 CE. Most of Egypt, including Alexandria, recognized his rule. Diocletian was forced to take a personal interest in the case. Ultimately, efficient command allowed the official government to take control of the inflamed region. Domitian died in December 297 CE. Only Alexandria, led by Achilleus, (corrector – administration repair official) defended itself until March 298 CE.

As a consequence of the uprising, Alexandria was forbidden to mint coins by itself. In addition, the Egyptian administration was largely brought into line with the Roman administration (steps to this end were already taken by Septimius Severus). Diocletian spent the remainder of 298 CE in Africa, arranging affairs at the southern border, before arriving in Mesopotamia in April 299 to meet Galerius.

War with Persia

In 294 CE, the militant Narses son of Shapur I rose to power in Persia. He eliminated the young Bahram III from the political game and took full power. In 295 or 296 CE he declared war on the Romans and invaded western Armenia. He drove out King Tiridates V from Armenia and attacked the Roman Empire. He defeated the legions near Cahrrae. Emperor Galerius arrived in the East in 298 CE (backed by a contingent from the Danube) and moved to Armenia, where the Persian cavalry was more difficult, and the legions that fought better there could use it. In the valley of Araxes in the center of the country, the Persian army was defeated, and the Persian camp along with the royal family fell into Roman hands. Galerius invaded Mesopotamia and took Ctesiphon. Despite the destruction of the Sassanid army, Emperor Diocletian did not annex the conquered lands, because he could hardly maintain order in the former territory of the Empire. Only the border in Mesopotamia was changed in favor of the Romans. Diocletian and Galerius won a great victory in the East.

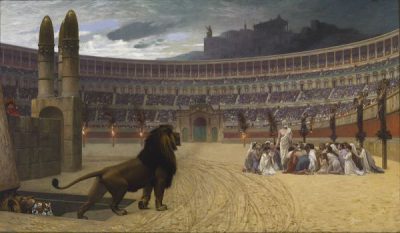

Persecution

Diocletian, looking for support for his power, decided to return to the ancient Roman faith. In this way, he would succumb to his rule in terms of ideology and propaganda. Diocletian strove to strengthen the mores of his ancestors (mos maiorurum) and he wanted to support traditional Roman values and cultivate the old religion. The power of the tetrarchs was to come from the traditional gods of Roman religion, especially Jupiter, Hercules, Mars, and Sol Invictus. Moreover, propaganda emphasized the divine nature of the emperors. In 302 CE, Diocletian issued an edict against the Manichaeans, which condemned the followers to death or lifetime labor in the mines, and the Manichean leaders to be burned alive with their books. According to Diocletian’s letter to the proconsul of Africa, Manichaeism was a new religion, alien and hostile to the inhabitants of the Roman world.

In early 303 CE, Christians were expelled from the army on the accusation that they were disrupting official religious ceremonies.

The persecution of Christians has begun on February 23, 303 CE, when officials and soldiers, on the orders of the emperor, destroyed the church in Nicomedia. The next day, an edict was issued ordering the destruction of Christian temples and the burning of holy books, and the deprivation of Christians in public office. The edict clauses were observed to varying degrees in different areas of the Empire. In Egypt, the prefect Josianus Hierocles forced sacrifices to pagan deities and liquidated churches. In the west, Constantius Chlorus made very little of these ordinances. A second edict, in the summer of 303 CE, ordered the imprisonment of Christian priests throughout the Empire.

In the fall of 303 CE, the third edict proclaimed that all who departed from Christianity would be set free, and the resistant ones could be tortured. As a result, in the eastern part of the Empire, many bishops and laypeople were imprisoned, tortured and killed. Bishop of Nicomedia, Anthimus, was beheaded. From this time of persecution, many accounts of the martyrs venerated in the Christian Church to this day have survived. However, the vast majority of Christians avoided persecution. The campaign was not carried out systematically and with the same intensity. There were differences in the execution of orders dictated by local conditions. Several hundred people paid their lives for their convictions throughout the Empire. They were mostly priests. The torture to which they were subjected was imposed by Roman legislation against all those who oppose state power; they were not specifically invented for Christians. The persecution was provoked by Galerius, who, as the son of a priestess Romula, was an implacable follower of traditional Roman religious cults. They ceased when in 311 CE Galerius issued an edict allowing Christians to cultivate their religious practices.

The picture of the persecution of Christians during the reign of Emperor Diocletian can be distorted because we only have relations from one side – the persecuted. However, the statements of various church writers and the further development of events indicate that the number of apostates from the faith was very large. Even bishops were among them. The case of the Bishop of Rome, Marcellinus, and of the Bishop of Alexandria, Peter, became famous.

Abdication

In the early winter of 303 CE, Diocletian visited the capital. On November 20, he and Maximian celebrated the twentieth anniversary of his reign (vicennalia), the tenth anniversary (decennalia) of the tetrarchy and the victory over Persia. On this occasion, great celebrations were held in Rome. Over time, however, Diocletian began to show uncertainty about what Lactantius (a Christian writer) claims about the “inadequate” greeting of the ruler by the inhabitants. On December 20, 303 CE, he left Rome and traveled north. He took over the ninth consulate in Ravenna on January 1, 304 CE. Then he went to the Danube and took part in Galerius’s campaign against the Carp.

His health deteriorated and he had to be carried in a litter. On August 28, 304, he was in Nicomedia. At the turn of 304 and 305, he went through the most severe period of the disease, when the people of Nicomedia were convinced that the emperor would die soon. Rumors have spread that Diocletian’s death is being hidden until Galerius arrives in the city. Diocletian did not appear in public until March 1, 305 CE, when people barely recognized him as a result of his illness.

On the same day, Diocletian called a gathering of officers and soldiers in the area of Nicomedia, near where he was proclaimed emperor in 284 CE. Galerius and Constantine I (later Emperor, son of Constantius) were also present. Diocletian appointed August Galerius in the East and Constantius in the West; and the Caesars of Maximina Daja and Flavius Severus. Then, with tears in his eyes, he renounced the dignity of Augustus, justifying this decision with his age, health and fatigue. He argued that someone much stronger must take his place. All of this took place at the statue of Jupiter, the patron saint of Diocletian. Maksymian also announced his resignation.

Most of the crowd realized what the political scene might look like after Diocletian’s resignation. Constantine I, together with Maxentius, the only adult sons of the ruling rulers, omitted from the division of the Empire, will take over (or will want) power as Caesars due to their family connotations. And such a turn of events did not bode well for the recently established (and doing well) tetrarchy system.

The system of government after Diocletian’s abdication | ||

| WEST | EAST | |

|

| |

|

| |

People who were left out of the allocation of power:

| ||

Death

Diocletian gradually withdrew from public life and settled in his Palace in Split near Salona on the Dalmatian coast. Maximian, in turn, moved to Campania or Lucania. Both did not take an active part in politics, but kept in touch with each other. At the request of Galerius, he and Diocletian received fasces in 308 CE and served as consulate. This fall, Diocletian met with Galerius at Carnuntum (Austria). On November 11, 308 CE, together with Maximian, he took part in the appointment by Galerius of Licinius to the position of Augustus in place of Severus, murdered by Maxentius. Diocletian also ordered Maximian to finally give up power, to which he temporarily returned to stop his son Maxentius.

The people of Carnuntum wanted to persuade Diocletian to return to power, but he refused to do so. Traditionally, during his retirement, he was to be mainly growing vegetables in the garden in Split.

Diocletian lived another three years spending time in his residence. He saw with his own eyes how the system he had introduced in the Empire was gradually deteriorating. The selfish actions and ambition of individual members of the Augusta family finally destroyed the durability of the tetrarchy. The system officially functioned, but the shifts in the political scene only contradicted its effectiveness. Maximian himself, a longtime co-ruler of Diocletian, tried to proclaim himself emperor in 310 CE, but was definitely defeated and forced to commit suicide. To make matters worse, Maximian was placed under the damnatio memoriae (“damn memory”) procedure.

Left alone and in grief, it is possible that Diocletian committed suicide. He died on December 3, 311 CE.

Marriages and Children |

|