Chapters

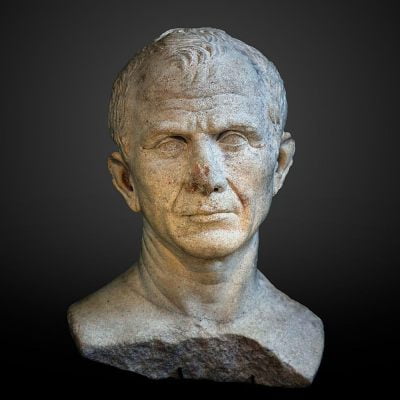

Julius Caesar took power in Rome after years of civil wars. Further signals indicating that he might wish to restore the monarchy sparked a conspiracy and his death. The assassination of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE is a decisive step towards the fall of the Roman republic.

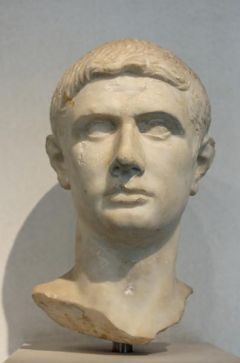

The opposition to Caesar was headed by Gaius Cassius Longinus and Marcus Junius Brutus. Longinus was previously associated with Pompey, after the defeat at Pharsalus he surrendered to Caesar, but still, he loudly expressed his dislike of him. It was similar to Brutus, who, however, was trusted by Caesar; moreover, Caesar had an affair with his mother, Servilia.

Reasons why some of the aristocracies hated Caesar

After the battle of Munda in Spain (45 BCE), in which Caesar finally dealt with his only opponents, the sons of Pompey – Sextus Pompey and Gnaeus Pompey no one was able to threaten Caesar’s authority anymore. On February 14, 44 BCE the Senate proclaimed Caesar the perpetual dictator (dictator in perpetuum), the high priest (pontifex maximus), emperor and “father of the fatherland.” Caesar concentrated in his hand enormous power, unprecedented in the Republic. Caesar did not fail to hide his unique position and when the senators visited him, he did not even get up at the sight of them.

In the Eternal City, rumours grew more and more about Caesar’s plans to proclaim himself king of Rome. However, when he was called the king of Rome, he replied: “I am Caesar, not a king”Suetonius, Caesar, 79" data-footid="1">1. His subordinate and commander, Marcus Antony, repeatedly tried to put the royal diadem on Caesar’s head; this one, however, refused2.

Moreover, one of the members of the college of fifteen husbands (the college for consulting the Sibylian books) – Lucius Cotta – applied for Caesar to be king because, as the holy books said, only the king could defeat the Parthians, and Caesar was planning an invasion east at that time.

All these events hastened the decision of the conspirators to murder Caesar in March 44 BCE

Conspiracy

The origins of the conspiracy are related to the talks in February 44 BCE of Cassius Longinus, Marcus Brutus and Decimus Brutus, who were increasingly afraid that Caesar would proclaim himself king. Cassius Longinus was a former soldier of Crassus in the Party expedition (one of the few to survive); Marcus Brutus originally joined Pompey, however, after his defeat at Pharsalus, he received Caesar’s forgiveness and held the office of governor in Pre-Alpesque Gaul, and then the pretext; Decimus Brutus, in turn, was Caesar’s officer in Gaul. They gradually included more conspirators into their ranks, so as to be able to form a group capable of self-defence, but at the same time small enough to keep a secret. We know the names of nineteen conspirators, they are: Gaius Cassius Longinus, Marcus Brutus (dealt the final blow), Publius Casca (dealt the first blow), Gaius Casca (dealt the death blow), Tilius Cimber, Gaius Trebonius (he stopped Mark Antony from entering the Senate), Lucius Minucius Bazylus, Rubrius Ruga, Marcus Fawonius, Marcus Spurius, Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus, Servius Sulpicius Galba, Quintus Ligarius, Lucius Pella, Sextus Nazo, Pontius Aquila, Turulius, Hortensius and Bucolian.

The involvement of Cicero and Mark Antony was also considered. In the case of the great orator, it was finally dropped, because it was feared that the Roman was too conservative for this task, and he was spending a lot of time in the circle of “Caesarians” in recent times. Antony, in turn, was not invited to the plot, as Gaius Trebonius revealed that he had once offered him an attempt on Caesar’s life, but the offer was rejected.

It is worth noting that not only Caesar’s optimists and rivals were involved in the plot. The circle of conspirators included, among others the aforementioned Decimus Brutus or Gaius Trebonius, which we would classify as “Caesarians”. Their motives are not clear; uncoiled that, apart from their dislike of Caesar’s autocracy, they were simply jealous of the higher positions of Antony and Lepidus, who had cooperated with Caesar for a shorter time.

An important source of information on the plot to kill Caesar is Nicholas of Damascus, who lived at the time. According to his account, the conspirators never met openly, but always several in one of them. There were many discussions as to how and where to implement the plan. Some have suggested that they should make a coup while Caesar oversees the elections in the Field of Mars; another idea was to throw him off the bridge during his election trip. The third plan was an attack during the gladiatorial fights. The advantage of the last plan was that no one would be suspicious of seeing the weapon prepared for the assassination.

But the overwhelming majority were in favour of killing Caesar while he was sitting in the Senate, where only senators are admitted (Caesar’s protection had to remain out of the entrance), and many conspirators could hide daggers under their togas. The plan was accepted.

Caesar was warned of the possibility of an attempt on his life, but he was always cautious about it, claiming that he would live in fear all the time if he was constantly surrounded by a bodyguard. At the same time, he was sure that no one would dare to carry out an attack, as it would trigger another civil war. Moreover, at that time was planning the aforementioned expedition to the East, which was to begin on March 18, 44 BCE, so he was out of his mind about possible conspiracies.

According to ancient sources, the planned murder was preceded by bad signals.

Now Caesar’s approaching murder was foretold to him by unmistakable signs. A few months before, when the settlers assigned to the colony at Capua by the Julian Law were demolishing some tombs of great antiquity, to build country houses, and plied their work with the greater vigour because as they rummaged about they found a quantity of vases of ancient workmanship, there was discovered in a tomb, which was said to be that of Capys, the founder of Capua, a bronze tablet, p109 inscribed with Greek words and characters to this purport: “Whenever the bones of Capys shall be moved, it will come to pass that a son of Ilium shall be slain at the hands of his kindred, and presently avenged at heavy cost to Italy.” And let no one think this tale a myth or a lie, for it is vouched for by Cornelius Balbus, an intimate friend of Caesar. Shortly before his death, as he was told, the herds of horses which he had dedicated to the river Rubicon when he crossed it, and had let loose without a keeper, stubbornly refused to graze and wept copiously. Again, when he was offering sacrifice, the soothsayer Spurinna warned him to beware of danger, which would come not later than the Ides of March; 3 and on the day before the Ides of that month a little bird called the king-bird flew into the Hall of Pompeyg with a sprig of laurel, pursued by others of various kinds from the grove hard by, which tore it to pieces in the hall. In fact the very night before his murder he dreamt now that he was flying above the clouds, and now that he was clasping the hand of Jupiter.

– Suetonius, Caesar, 81

On a critical day, however, Caesar almost did not thwart the assassins’ plans. His wife, Calpurnia, begged him to stay at home, as she had had bloody nightmares the night before. She was going to dream of a collapsing ceiling and a dead husband in her hands. Caesar reluctantly agreed to her request, as he also did not feel well that day. Ultimately, however, visiting Caesar, Decimus Brutus persuaded him to go to the senate’s deliberations, because senators were waiting for him on the spot from the morning.

While travelling from the home of pontifex maximus3(the so-called Domus Publica) to the Forum Romanum to the Field of Mars, Caesar received a scroll – from a certain Artemidorus – with information about a conspiracy on his life. Caesar, however, in a hurry, hid the correspondence for later. In addition, Caesar also visited the house of friends before finally going to Pompey’s theatre.

We also have information that before Caesar entered the theatre – perhaps while he was at home – the priests sacrificed several cattle to the gods to undo the evil omens that were to precede the deliberations4. However, subsequent omens were unfavourable, as the soothsayers were unable to find the animal’s heart. Caesar, in anger, left the soothsayers, although the priests continued, looking for good signals.

During the sacrifice, Caesar was supposed to talk to Augustin Spurynna, who warned him about the Ides of March. Interestingly, Caesar was to say that there was nothing to fear because the ides had come and nothing happened; to this Spurynna was to reply that they were not over either.

It may seem that Caesar made the decision to go to the deliberations, despite numerous bad signs and signals because he wanted to demonstrate his strength. He did not want the senators, among whom he knew he had many enemies, to later accuse him of cowardice and weakness.

Day of the assassination

Caesar arrived at the Senate’s deliberations, around noon (meridies), on March 15, 44 BCE (referred to as the “ides of March” in the Roman calendar), which were held at that time in the part of the portico of the Pompey Theater bearing the name Curia Pompeia – the room intended for the meetings of the Senate (more or less the western part of the Largo Torre Argentina road). Mark Antony, as the second consul besides Caesar, was deliberately dragged away before entering by Gaius Trebonius so as not to disturb the assassins. Upon entering the building, Caesar took his place on a gilded chair.

It is worth noting that on that day the gladiator fights in Pompey’s theatre were also to take place, therefore the entrance to the theatre was probably heavily crowded, especially since Caesar did not show up in the morning. We also know that after Caesar’s murder, both senators and the audience left the theatre en masse.

The then senate numbered 900 senators, but that day the turnout was very low and their number could be from 200 to 300 members.

After Caesar sat down in his chair, Tillius Cimber approached him, asking for grace for his exiled brother. Other initiates began to follow him. Caesar, irritated by Cimber’s gradual insistence, tried to get up, but then Cimber tore his toga off his shoulder, which was to be an agreed sign for everyone to attack. The first blow was dealt to him from behind by Publius Servilius Casca (with whom Caesar had known from his adolescence), but the strike was inaccurate and only slightly injured Caesar. Both men started to struggle, and the other shocked conspirators did not react. Meanwhile, Caesar was about to shout: “Casca, what are you doing?”5in return by knocking his shoulder with a stylus.

Terrified Casca, in an uproar, called in Greek to his brother Gaius: “Brother, help me!“. There was a commotion and Cassius Longinus approached Caesar and struck him a punch in the face; then the summoned Gaius Casca stabbed the dagger between the victim’s ribs. Another Decimus Brutus hit the thigh, and Cassius Longinus pulled out again, but this time he missed and wounded Marcus Brutus in the hand.

The last blow, dealt by the hand of Brutus, whom Caesar considered a friend, turned out to be decisive – he hit between the legs, in the groin. Julius Caesar, seeing Brutus, was supposed to shout in Greek: “you too, child?”6, which could be either a threat or a regret. The commonly used version: “you too, Brutus?” (Et tu, Brute?) is an invention of Shakespeare.

After these words, the Roman fell, covered with his own toga, at the foot of the statue of Pompey, his former supporter and enemy. Some of the conspirators went to the body and stabbed Caesar’s body with daggers to have their symbolic involvement in the murder. According to Plutarch, Caesar was dealt a total of 23 dagger blows (which would indicate a strict group of conspirators), and we only know from sources about the above five injuries inflicted on Caesar while he was alive; it is possible that the next wounds were inflicted just after the dictator was already dead. According to the account of Nicholas of Damascus, 80 people took part in the plot, while Suetonius claims there were 60. The number of wounds inflicted proves that a large part of the conspirators took part rather passively.

Situation after Caesar’s death

After this event, a pale fear and uncertainty fell upon Rome. The assassins scattered in fear and headed for the Capitol, fearing that the “Caesarians” would go against them with military force. Along the way, they shouted and raised slogans for freedom. Terrified by the situation, the people initially hesitated in assessing Caesar’s death. But the touching and thrilling Mark Antony’s funeral speech seized the audience a few days later and turned the blade of anger against the attackers. According to Appian’s message7, upon the news of Caesar’s murder, a wax statue of a dictator was erected at the Forum Romanum, on which 23 wounds were indicated. Caesar’s body was burnt at a huge funeral pyre – a temple of the Divine Caesar was later built on this site. The crowd was said to be agitated and set the surrounding buildings on fire. Moreover, “immediately after the funeral, the commons ran to the houses of Brutus and Cassius with firebrands, and after being repelled with difficulty”8.

Despite the initial agreement between the “Caesarians” and the attackers, the situation changed rapidly over time and an order was issued to prosecute the criminals. Within two years, all of them died – in battle or on their own. None of the perpetrators of the attack died of natural causes.

Caesar did not manage to complete the plans for the conquest of the Daks and Parthians. In his will, Caesar made his heir Octavian, grandson of his sister Julia – the future first emperor of Rome.

Autopsy of Julius Caesar’s body

After the murder of Julius Caesar on March 15, 44 BCE, the conspirators originally planned to dump the former dictator’s body to the Tiber. Ultimately, however, for unknown reasons, they left a bloodied body in Pompey’s theatre. Thanks to this, doctor Antistius was able to perform an autopsy.

Suetonius – a historian, writing about two centuries later and using earlier sources – reports that three slaves placed the body in a litter and carried it home. There, too, Antistius – probably Caesar’s private physician – conducted the autopsy. In total, he noted 23 wounds (including on the face or groin) that resulted from dagger blows.

The fatal blow was delivered under the left shoulder, between the ribs. It was deep enough to reach the heart and could violate an important aorta. Thus, the dictator died of internal bleeding. Blood filled his chest and then the lungs collapsed.

In 2003, a team of experts under the supervision of the Italian investigator Luciano Garofano decided to conduct a modern investigation. Using technology, it was possible to create a three-dimensional reconstruction of Caesar’s body. A team of pathologists, policemen and historians drew conclusions based on the sources and knowledge of the behaviour of people in the crush and affect.

According to Garofano, it was impossible for 23 men to be involved in a direct murder. It is more likely that 5 to 10 men were involved in the killing, while the rest were simply surrounding the incident and allowing other senators to inflict blows.