The year 31 BCE began a new stage in the history of the Roman state. Octavian’s success, crowned in 27 BCE, created a new political system – the empire.

Following Giza Alföldy’s opinion, it can be said that the first two centuries of the empire were “the peak period of the development of Roman society”1. Thanks to the newly created political framework, a period of prosperity have begun. The following years, although much less favourable in economic and social terms, continued to shape social and economic relations. As a result, a new Greco-Roman entity was to arise in the Eastern Mediterranean – the Eastern Roman Empire.

What are the “Eastern provinces of the Roman Empire”? In this article, I consider Macedonia, Achaea, Lower Moesia, Thrace, the provinces of Asia Minor, Syria, Judea, Arabia, Cyrenaica and Crete, Cyprus, Egypt2. I will not include the Mesopotamian province in the article, because the annexation of these areas to the Roman Empire was impermanent, and the reign of the Romans over the Tigris and Euphrates was very unstable3. The Romans introduced a system of client states in the East – it retained power in the hands of local dynasties that were focused on cooperation with the invaders – however, the policy of the emperors: Tiberius, Claudius, Vespasian, Domitian and Trajan sought to fully subordinate the eastern territories to Rome by adding client countries to the Empire and organizing new provinces there. Absorption in 106 Nabatei completed the work of connecting clients to Rome.

It should be emphasized that Rome did not create the eastern provinces from scratch. Legions conquered mostly civilized areas, at a high level of development, with a long history and old traditions. Contrary to the West, the post-Hellenistic area was highly urbanized4. The polis-type towns were widespread after Alexander’s conquests prevailed. Urbanization, however, was not even, most of the urban centres were located on the coast of the Black Sea and the Mediterranean Sea (except Egypt5) and going into the mainland one could find fewer and fewer of them (Cappadocia, Macedonia, Syria except Ten-Towns6). The first century of the empire brought some changes in this respect. Octavian’s work was to transform temple states into cities and to create Roman colonies. Some of them were built on the site of former Greek cities (Corinth), or next to run-down poleis, located in less urbanized areas of Macedonia (Philippi), geographical Achaia (Patras), or Acarnania and Illyria (Dyrrachium7). Successive emperors continued the policy of founding cities8. In Asia Minor, where the network of urban centres was very irregular (Ionia, up to the Bosphorus was characterized by strong urbanization, inland there were few cities created before Actium), huge swathes of the Anatolian Plateau and Pontius were deprived of urban centres9 . Julio-Claudian emperors created colonies there, often in place of already existing cities (eg Neoclaudiopolis instead of Andrapa-Neapolis).

The the Flavian dynasty sought to urbanize non-Hellenized areas by granting the status of a city to local centres of social life. Hadrian played a large role here. As a result, most of Anatolia was covered by cities, including the inaccessible areas of Cilicia and Pontus. Syria and Palestine, as I have already mentioned, were poorly urbanized. The exception was Ten-Towns – the area between Syria and Palestine – covered with ten polis-type cities. The founding of cities in Palestine was the work of Herod the Great and his successors (e.g. Herodeon, Caesarea). Egyptian metropolises10, despite their small size and the lack of municipal administration, were considered by the Hellenes as cities, because the Greeks considered every place of social life organized around the gymnasium as a city. In fact, Egypt had only four polis-type cities, but one of several hundred thousand – Alexandria11. It was only the Romans that began granting the status and city organization to the Egyptian metropolises. The year 200 can be considered the moment when Egyptian metropolises became fully-fledged cities when Septimius Sever created boules – city councils, administrative12. In addition to this formal elevation of the metropolis, the only founding of the city was made by Hadrian (Antinoupolis dedicated to the memory of the imperial ephebe13). Also, Nabatea was only formally urbanized. After joining the Empire (106), the status of indigenous centres (eg Petra) was raised to the rank of a city. In short, the policy of founding cities or “reviving” decaying centres was intended to revitalize less populated territories economically. Veterans were settled in the colonies (especially Octavian after Action ) to cultivate the granted land while creating a new outlet for the natives. It would not be an exaggeration to say that the founding of new cities played a large role in the economic recovery of the East during the principate period.

Just as the level of urbanization in the East was irregular, its economic development was also irregular. The empire made possible the peaceful, unwavering development of most provinces. Introduced by Octavianpax romana, it guaranteed peaceful conditions for economic development. As already noted, the state of prosperity was achieved, among other things, by the emperors’ urbanization policy, but that was not the only reason. An important novelty in relation to the decline of the republic was the limitation of the robber policy of the provincial governors. Until now, governors treated their work as an opportunity for quick earnings. This, along with ignorance of the local realities, led the provinces to economic ruin. Arriving for a one-year term, they tried to earn some extra money. The Principate opposed this attitude. A salary for governors was introduced, amounting to 1,000,000 sesterces in the case of the most prestigious provinces. Officials were often kept in the provinces longer, an example of which is Pontius Pilate, the prosecutor of Judea, who, thanks to his skilful management, managed to stay in office for a long time14. There is a visible tendency to use people from the East in the administration (e.g. from senatorial families settled in the East). A manifestation of this policy was to leave the local rulers in the client states I described earlier (eg Herod and his successors). Sartre states that in this case, it is more likely that the client kings were to prepare their kingdoms for full incorporation into Rome15. Moreover, the empire allowed city officials to file complaints with Rome. Although the trials did not always end with a sentence, the very awareness that the governor could be held accountable effectively deterred excessive exploitation. All these activities allowed the eastern provinces to revive. In agriculture, the basis of the economy was Egyptian grain. In historiography, it is accepted that Egypt was the granary of Rome. Jaczynowska reports that as much as 1/?of the grain imported to Rome was Egyptian grain, already ancient historians claimed that Rome was in danger of starvation without Egypt16. Nevertheless, as T. Łoposko writes, the Egyptian grain was “only a kind of supplement”Caligula. So power in the hands of a twenty-year-old." data-footid="17">17. However, its importance should not be depreciated, even if it was not so important for Rome. Its exports kept a huge number of people – Egyptian farmers and traders. The craft was developing dynamically, the main centre of which was Alexandria. Clothing, papyrus, the famous colourful Alexandrian glass and jewellery were produced here. Based on this information, it can be concluded that for backward Egypt, which was dominated by technologies and social relations from the Lagid era18, Alexandria was a huge centre of production and, for farmers on the Nile, the main market. Emperors, striving to maintain the system from the previous era, supported the relations that existed here. This was reflected in the Vespasian law prohibiting the dissemination of technological innovations. The reason was to care for the artisans – they would lose the possibility of earning money if these innovations were introduced to the market19. For Asia Minor, the principals began a period of strong development. The above-described urbanization process has created new outlets for local agriculture. Asia Minor itself could finally breathe after the wars of the 1st century BCE.

It is assumed that the great property in Asia had a significant market share, on the other hand the widespread distribution of grain suggests that many people did not own the land20. Large property developed, often imperial. As Geza Alfoldy writes, due to the decreasing supply of slaves, their position improved21. There were more and more liberations, it was accepted that a slave should be released after a certain period of service. Peasants worked in the Anatolian fields, and slaves found employment as administrators. Due to their good social position, they were sold into slavery, it was a way to improve their fate and obtain Roman citizenship. These changes were introduced to Anatolian land through imperial possessions. Princepsi sought to improve the fortunes of slaves, often using them in matters of vital importance to the empire. The economies collapsed in Greece and Macedonia. Much of this was due to the devastation of the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE. The depopulation was so great that Plutarch wrote that it was possible to cross the country with only a few shepherds. The emperors, in the words of Hadrian: “I prefer that the empire should be strengthened by the growth of its population rather than its riches”, supported the reconstruction of these areas. Colonists were encouraged to settle in Greece, they were to obtain land by dividing up communal estates. The use of landless peasants or those who owned small pieces of land became common, which heralded the emergence of a new social group in the next century – the colonies. These actions did not make Achaia together with Macedonia a vital element of the Roman economy, but undoubtedly actions were taken to overcome stagnation, but with such agricultural regions as Spain, Africa or Egypt, population growth should be considered a success22.

In Palestine, power was handed over to the local Herodian dynasty. This move was undoubtedly aimed at economic development, after all, who knows the problems of a given region better than a person from an early age who has contact with politics23? This policy of the emperors seems to be the most rational, especially in the case of such a troubled province as Judea, where the Augustinian policy was not always right. The Jews, as monotheists, were unique in the world of many gods. The lack of sense of emperors (Caligula demanding divine worship24) and prosecutors (Pilate trying to build an aqueduct with the money of the Temple25) led to social discontent. The War of 66-70 CE was the bloodiest, but not the only one, rioting had happened earlier, and also in later years (132 -135 CE – the rise of Bar Kochba).

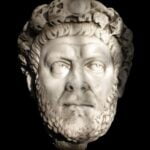

In the 1st and 2nd centuries, the national structure of the senate changed. From Marcus Aurelius, most of the senators came from the provinces26. The “conscription” of senators took place mainly in well-developed provinces. The richest notables, often descendants of royal families, were admitted to the senatorial state27. The Roman elite became Hellenized. Knowledge of Greek was in a good tone, literature based on Greek patterns (Horace, Virgil) flourished, historiography (Diodorus Siculus) and philosophy (the development of Neoplatonism, Roman philosophies: Seneca, Marcus Aurelius). Eastern religions (the cult of Cybele, Mithraism, Sol Invictus) grew in strength. It was from Hellenistic culture that the idea of deification of emperors was born, which the Greeks recognized even before its official introduction28. Hellenistic culture was promoted by emperors (Hadrian was the first emperor to “wore” in Greek; Aurelius – philosopher of the Stoic school). The growing interest in the East led to the Hellenization of the elite, and thus the cultivation of Greek ideas.

The Act of Septimius Severus of 200 CE introduced boule in every Egyptian metropolis. Anna Świderkówna believes that the introduction of city councils was not a success, on the contrary – it contributed to the fall of cities29. The political crisis of the third century influenced the socio-economic situation of the East. The emergence of the Sassanid state implied invasions of Syria, Asia Minor and Egypt. As a result of the wars, the economic activity of the decurions, who in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, by financing the cities, improved their situation. The introduction of boule to some extent “tied” them to the cities. Until now, the dekurioni financially supported the poleis voluntarily, since then it has been their duty to maintain them. Additionally, the possibility of leaving the state of decurions was limited, introducing almost its inheritance30. This policy, despite the fact that it is aimed at ensuring income for the cities, led to their gradual decline. The decuriones, burdened with excessive spending, tried to pass on their obligations to the cities.

The increase in state benefits hit the rural population hard – Oxyrynchos was threatened with depopulation as the peasants were unable to pay the taxes levied on them. At the same time, Roman officials had no resistance in collecting taxes. In Asia, collectors robbed people of the most necessary livelihoods. The colonate31became popular in the countryside, and it was supposed to ruin the peasantry in the next century. A manifestation of opposition to the oppression was the uprising of the boukaloi (CE 172-173) – shepherds of cattle from the Nile delta.

The Diocletian reforms of 286 introduced a division of the empire between equals32. A new political framework began to take shape. In the 4th century, curiales (formerly known as dekurioni) finally lost their importance. The victory of the Christians revolutionized social relations, especially in the countryside, where the decline of slavery to the colony became a reality. Geza Alföldy claims that while the colony used to be a prospect of improving its fate, now it was tantamount to the loss of personal freedom3334. Subsequent problems of the empire in foreign policy proved that it was no longer possible to rule over such a large territory. The death of Theodosius I in 395 finally divided the empire. The “Roman East” became a new political entity – the Eastern Roman Empire.

To sum up, the emperors’ policy was aimed at the socio-economic development of the province. Leaving client kings in the provinces, developing urbanization, settling veterans in the East, supporting Hellenistic culture and supporting agriculture, were all aimed at developing the provinces. Supporting the existing social relations was intended to protect the poorest people and support cities. This policy, although it caused regression and started feudalism, cannot be considered a deliberate act against the provinces. The attitude of the emperors to the notables from the east was friendly. The state of senators was often supplemented with the most honourable people of the East, and the Romans themselves aspired to be part of the Hellenistic culture. Internal policy errors, implying social conflicts, were caused by the lack of intuition of the central government as to regional social relations and, like the errors of economic policy, cannot be considered purposeful.